The Eyes of Manukan (1981)

©1981, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Denny, Dallas. (1981). The eyes of Manukan. Unpublished novel.

The Eyes of Manukan is a fantasy novel. I pounded it out on my venerable IBM Model B typewriter. Several years later I would be writing on my new VIC-20 computer.

The Eyes of Manukan

A Fantasy Novel by Dallas Denny

Synopsis

Synopsis

The Eyes of Manukan

This is a fantasy novel. The text is approximately 270 double-spaced typed pages in length, and is divided into three books, a prologue, and an epilogue.

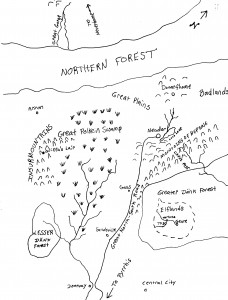

Eyes is set in a time in which magic is as real as the crossbow. Great sorcerers struggle against each other, and dragons occasionally terrorize the countryside. There are men, and demi-humans: elves, dwarves, orcs, and halflings. Each group has its own priorities, but factions have been known to band together to fight great evils.

The evil wizard Smendra has succeeded in evoking and controlling the demon Silarith. Smendra uses Silarith to further his aims of controlling the world. From his fortress in the frozen wastelands of the north, Smendra sends Silarith on nightly forays in the Southlands.

Silarith is indestructible. Nothing of this world can harm him. However, Fangale, another sorcerer, has succeeded in creating a weapon which can harm Silarith. The weapon is a sword called the Eyes of Manukan. The Eyes is constructed of two parts, the Left Eye and the Right Eye. Separately, the halves have no special power, although they are useful as weapons. When they are joined, however, they draw upon the powers of a mysterious entity called Manukan.

The Eyes can be wielded only by a descendant of the royal Elven family. All of the members of this family are thought to be dead, but Fangale has located a survivor, who was raised by humans, and who is ignorant of his birthright. Fangale tells Shoin, known as Sean to the humans, about his heritage, and about the danger to the world. Sean agrees to help Fangale defeat Smendra.

Sean sets out along for the Elflands, but before he reaches them, has an encounter with Silarith. He is set up by an Elven viscount who fancies the girl with whom Sean has fallen in love. Sean evades Silarith and makes his way to Genre, the Elven capital, where he meets Serath, a dwarf, and Brandon, a human minstrel. Serath and Brandon are imprisoned, and Sean rescued them and Berryl from the dungeons of Neador. Berryl, the son of the king, has been locked away because the king thinks he did away with his brother in order to inherit the throne. By disguising himself as a woman, Sean gets into the dungeons and rescues the trio. They then make their way toward the Dark Lord Smendra’s stronghold. The war is on, and they return to the Southlands and help Fangale raise an army.

When the armies of the Dark Lord and Fangale clash, the Dark Lord’s forces prevail, and Silarith carries Fangale away. Sean manages to cling to the monster’s leg, but is locked away in Silarith’s lair, presumably to be tortured and eaten. But Sean is rescued by Cato, the seventh cook of Neador, and makes his way to the Northlands. There, he manages to trick Silarith and return him to his own plane. Silarith, freed from Smendra’s control, drags the screaming wizard into the pentagram, and they both vanish with a puff of smoke as the badly injured Fangale recites the spell to banish Silarith. Sean is disconsolate because he fears he cannot reach the Elflands before his eighteenth birthday, thus forfeiting his crown. But Fangale takes care of that, and everything is hunky-dory. Finis.

Dedication

For Wendy

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michael Blankenship, and especially Wendy McAmis, for reading early versions of the manuscript. Their criticisms and suggestions helped to make this book far better than it would otherwise have been.

Prologue

Prologue

Many years before, the great forest had been light and airy, full of dancing lights and abundant with game. Now it was a dark and solemn place, a tangled, dreary expanse that stretched for hundreds of miles. A mist, gray and reeking, lay thick about, obscuring vision after only a few yards. Although it was fully ten o’clock on a morning in mid-September, the air was dank and chill. The mist, which on most mornings would have been burned away by the sun, was visibly thickening, its tendrils reaching and grasping at the twisted trees. As far as one could see, twisted trees leaned crazily, their bark coarse and rough. Many of the great trees were dead and others dying, and those that had fallen were carpeted with great masses of moss and fungi. Here and there a tall oak or maple, uprooted in the fury of some storm long past, tilted crazily, prevented from falling by the giants to its every side, rotting in place. Creepers and vines as thick as a man’s arm hung, unsullied by any breeze, and brambles and tangles grew in profusion wherever a gap in the huge trees let in the sun. Leaves were thick underfoot, their red and orange and yellow autumn colors muted by the shadows. They made a thick, brown blanket on the forest floor, hiding dips and hollows, roots which could trip an unwary passerby, holes which could turn an unsuspecting ankle.

The silence of the wood was ominous and pervasive. It was as if all sound were swallowed here, as if no forest creature, from hooded owl to shrew to the fat white grubs in the moldering undergrowth would dare disturb the pervasive quiet. Even the occasional fat raindrops spattered silently on the forest floor. Now and again a leaf turned under with the accumulated weight, spilling a stream of water noiselessly onto the ground. The silence was like the hush of a crowd at a theater just before a great actor first walks onstage, like the false peacefulness of a countryside before a tornado. The wood was as still as the bones of the great long-fanged cat strewn haphazardly at the base of a moss-covered boulder. It was the quiet of the great Northlands, a land once bright and alive with the chirping of insects and birds and the rustlings of small mammals, but now dark and forbidding.

Then the forest changed in a small way; from the north came, faintly at first, the dull sound of the hooves of horses on wet ground. The noise grew steadily louder, joined soon by other small sounds—the sucking of a hoof being pulled from mud, a hoof slipping on a bank, the creak of saddles, the jingle and clink of metal on metal. Suddenly four mounted figures, haggard and dispirited in appearance, appeared in the haze.

The leader, following the faint trace of an old game trail, occasionally leaned far over, inspecting the ground. He sat his horse easily despite his obvious weariness and despite the orcish arrow that protruded from his left shoulder. His gray eyes darted left and right as he searched the ground. At his side he wore a magnificent longsword, sheathed in a scabbard of brown leather. A single large jewel was mounted like a red eye in a hilt forged from some dull metal. A bow of yew wood was strapped to his back, the remnants of its snapped string dangling limply from either end.

The man was clad in a coarse gray cloak which overlay a vest made of the finest chain mail. His clothing was soiled and tattered, but obviously of the finest material and design. His face was fair and stern, with a chin that conveyed a decisive and resolute nature. His singleness of purpose was echoed by his hard gaze. He carried no fat on his six-foot frame. His name was Berryl, and he was the son of a king.

Sitting awkwardly astride the second horse was a creature as squat and thick as the first rider was lithe and tall. His braided red beard cascaded over heavy plate armor, extending fully to his stout waist. He clung to the mane of his mare with both hands, as if fearful of falling. His mount was of unusual size for a dwarf—much too large, but then, she had been hastily selected. The stirrups were tied in knots, as his stumpy legs were too short for even their highest adjustment. A crossbow was lashed to his saddle, and the head of a massive hammer was just visible above his belt. The handle had been cracked and bound together with strips of rawhide. His bright blue eyes advertised the fact, for all who might have cared to look, that however short he might be in stature, he would prove a deadly foeman. His name was Serath, a common enough name for dwarves, although rare among other races.

The third rider sported a sash embroidered with crimson thread advertising his name. His young face was pale and bloated, suggesting a life of dissipation. He looked soft and round, but any of his fellows could have attested to the muscles hidden under his fat. He wore his hat cocked at a jaunty angle, and the neck of a seven-stringed instrument protruded from a saddlebag. A sheathed rapier bounced his side. His name was Brandon.

The horse of the last member of the party was tied to Brandon’s saddle by a length of rawhide. The rider himself was doubled over the saddle, lashed into place with vines. He rode face down, unmoving. His face, could it have been seen, would have been notable for its resemblance to Berryl’s. His tunic was rusty with dried blood. A sword like that of his brother was fastened to his saddle. The green jewel in its hilt glinted now and again in the dim forest light.

Suddenly the first rider held up his hand, halting the party briefly as a large brown bear sauntered across the path just ahead. “Galmore’s wrath!” exclaimed Serath, whose mare was showing signs of nervousness. “Be still, foolish creature.” The bear disappeared without giving the party a glance, and they rode on for several silent hours.

Berryl seemed relieved when the end of the wood came into sight, but it wasn’t until he had led the small group well into the mist-shrouded plain that he stopped, dismounted, and put his ear to the ground for a long minute. Serath and Brandon stilled their horses and watched him intently. Berryl stood and said in a terse voice, “It’s as I feared. There are twenty or more riders. The mist will hide us from their sight until they’re almost upon us, but the ground is soft from the rains and will show our tracks clearly. There’s no hope of outfighting and little hope of outrunning them, for they’re fresh and our horses are weary. And there are none we may count as friends in this far Northland.”

He paused briefly. “I have a plan, such as it is. We had best part and ride in separate directions. Each of us must try to get word to Fangale.” The others nodded in grim assent. Brandon grabbed the handle of his sword, as if to be assured of its readiness. Serath glared through his thick brows, but neither spoke. Berryl continued. “Serath, you and Brandon head to the south and east; I’ll go to the south and west. As for my brother…” Suddenly, the great sword was in his hand. He lay his hand on the bridle of the dead man’s horse and with a quick movement cut the cord which secured it to Brandon’s saddle. “I regret, dear Randall, this must be done, and yet it must. I hope you can find it in you, wherever you may be, to forgive me. You lived fighting this menace, and you died fighting it, and I would not have your death be in vain. Nor do I think you would do differently if you were in my place.” He kissed the dead man full on the mouth, then, drew his brother’s sword from its sheath and slapped the horse smartly with the flat of the blade, sending it snorting into the mist with its burden. “Lead them a merry chase, dear Randall,” he said. He stared at his brother’s sword, which, except for the gem set into the hilt, matched his own. “I promise you, my brother,” he said, in a tone low enough so neither Brandon nor Serath could hear, “I promise you, I’ll find some way to put this weapon to good use.” He remounted his horse and without looking at either of his companions, galloped into the mist. Brandon and the dwarf caught each others’ eyes and, as the sound of hoofbeats was growing quite distinct toward the north, galloped away in a direction somewhat to the east of Berryl’s.

Book I, Chapter I

Chapter I

Sean The Merchant’s son had always felt as if he didn’t belong; not in his home, not in his village, and above all, not in his skin. An orphan, an elf, he had been found as a two-year-old, wandering and nearly frozen, a mile from the ashes of an ambushed caravan. The other members of the party being dead and their valuables stolen, the villagers who had found the toddler had no way to determine who he was. He was able to tell them only that his name was Shan. The villagers interpreted the name as Sean, and so that was what he was called. Sean had been raised by a merchant in Blackduck, a settlement a few miles east of the spot where he had been found. At first the childless merchant and his wife hadn’t dared hope they would be allowed to keep the boy, but as the months passed without news of a missing Elven child, they realized enthusiastically Sean was theirs to keep.

There were no surnames in Blackduck, so Sean was called the merchant’s son, as his adopted father had been called in his own fair youth. But although Brent the Merchant and his wife Greta had been good and loving parents, blind to the pointed ears and lithe build of their adopted son, there were many in the village who feared and hated elves, and Sean’s lot hadn’t been easy. Many of the adults would snub him or snicker and make jokes, and the children would pester and tease Sean, making unkind remarks about his ears or his long, slim fingers, or his flaxen hair. “Must be of Elven make,” the villagers would say when a plow broke or a bowstring snapped. “Ugly as an elf,” they would say of Sanford Skrimes, whose body was twisted and misshapen.

In truth, the elves were hardly an ugly people. Graceful in motion and slight in build, they moved with a natural speed and lightness unequaled by even the most accomplished human athletes—and few humans could manage the Elvish language, with its haunting enunciations and striking consonant sounds.

Perhaps it was the grace of the young elf that caused the village headman, Dawson Rotter, to take a dislike to Sean, for Rotter was bearlike in disposition and in appearance, with a coarse mat of brown hair that covered his body. Skin shows only on his hands, around his eyes, and on the top of his head— and there his pasty, puffy skin showed warts and scars. Sean learned to avoid Rotter early on, for to stray too near him meant a cuff or a kick or a curse.

By the time Sean was six, he had begun to feel an outcast in the village. As he swept the board floor of his father’s store or stacked merchandise on the crude pine shelves and when he lay in his bed on warm evenings he would daydream of far-off lands, of kings and adventures and riches beyond understanding.

Sean’s continual daydreaming served to get him into trouble; at the age of eight, because his heart was obviously not in running his father’s emporium, he had been apprenticed to the village blacksmith. On the third day of the apprenticeship, the blacksmith, a man of little patience, had accosted Brent on the street and in plain sight of half the village had ripped Sean’s contract into tiny pieces. He let it be known Sean was lazy and good-for-nothing. “He can’t even keep the bellows moving evenly! All he does is mope about, staring into space.”

This hadn’t helped Sean’s standing in the village, and since no other would take him as apprentice, his father put him back to work in the store, hoping he would one day warm to the life of the merchant.

Raymond hadn’t liked that at all. Raymond was six years older than Sean, a surly lad who had been apprenticed to the merchant since before Sean’s arrival, and who had great expectations of one day becoming partner in the enterprise. Raymond constantly undid Sean’s work and blamed Sean for his own mistakes, until poor Brent became convinced his son was little better than a halfwit. Brent began to treat Sean in a kind, but condescending manner, speaking slowly and carefully. This served to drive Sean further into his imagination; the daydreams grew more fanciful—he rescued beautiful maidens, duelled with evil villains, slew loathsome monsters, all without leaving the safety of his father’s store.

Raymond loved to listen to the talk of the village loafers, dressed in homespun and eating pickles and dried fish, as they joked and spun tales by the fireplace. But Sean lived for the occasional traveler who would spend the night impressing the villagers with tales from the great world which the men of Blackduck had never seen.

Yet Sean was unhappy with mere tales and daydreams. Like all daydreamers, he felt he was special in some way, destined for great things. He convinced himself he was more courageous and quicker of wit than his fellow villagers; sometimes he even preatended he was noble birth, the heir to a great and wonderful fortune. The daydreaming continued as Sean approached adolescence, and by the time he was seventeen he had grown to be a handsome, slender youngster who seemed to the townsfolk addle-pated and out of touch with reality. Raymond grew increasingly confident he would be selected to run the store, and even became a little protective and paternalistic toward Sean when the other youths refused to let Sean join in contests and games.

“Don’t worry,” Raymond told Sean one gray October morning when he was feeling unusually mellow. “They’re only jealous because they can’t match your wit or storytelling ability. Besides, they’re envious of your mysterious past.”

“Do you really think so?” asked Sean, leaning on his broom. He watched as Raymond deftly spat a stream of tobacco juice through a knothole in the pine floor of the store.

“Sure I do,” replied Raymond. “Aren’t you the fastest runner in the village? Aren’t you the quickest at dodging games and the most difficult to pin at wrestling? And wasn’t it your idea to dig a pit to catch the great cat that was killing the cattle?” Sean smiled as he though of the sabre-toothed cat, unable to climb out of the pit, leaping and snarling. The menfolk of the village had come and killed it with stones and arrows. Its hide, scraped and tanned, now hung on the north wall of the store, above the great stone fireplace, and the great teeth were affixed to a wooden plaque just beside it.

“I thought they would be happy about that,” said Sean glumly, “but they merely seemed more angry at me than ever.”

“That’s because your suggestion didn’t fit with their conception of you as a halfwit,” replied Raymond, surprising even himself with the observation. “You must—” He looked up and saw Sean’s father entering the room, carrying a bowl of stew. “—and how many times have I told you, lazy boy, you must always sweep the dirt toward the door and not away from it? Can you never get it right?”

Sean, who was used to such abrupt changes in Raymond’s demeanor, sighed and began sweeping, hoping his father hadn’t heard Raymond’s criticism. But his father handed Raymond the stew, asking him if he would mind eating alone for once, and walked up to Sean. Sean braced himself for a reprimand. Instead, his father merely shook his head sadly and said, “Son, please come into the kitchen. Your mother and I must have a word with you.”

Sean did as he was told, following Brent to the kitchen. Greta was huddled in a corner, her face buried in her hands, oblivious to the smell of burning bread that was beginning to fill the room. Brent removed a loaf of blackened bread with a long-handled wooden scoop and placed it on the table, where a pot of rich stew was growing cold. He put an arm around his wife and helped her to her feet, leading her to a chair. There she sat, red-eyed, looking at Sean with an expression full of love and longing. Sean and Brent took their respective seats, and Brent filled the three hand-painted porcelain bowls on the table with the meaty stew. After tearing off a chunk of bread and buttering it, Sean looked at his parents expectantly.

Brent smiled at his son. “Sean, your mother and I are growing old, and for some time now we have had reservations about whether you would be able to manage this place when we’re gone. You seem to be constantly making mistakes, yet you never learn from them, and months later you’re still making the same errors. Why, just now you were sweeping dirt back into the store. This is why we’ve not given you more responsibility in the running of the store. But we have loved you because you are our son.” He stared into the distance. Just then Raymond burst into the room, deposited his empty bowl, announced he had a customer, and left.

Brent continued. “This afternoon a stranger came to town. He is an old man, a strange man, but he said he’s here for a purpose. Before he even unpacked his burro, I overheard him telling some of the townspeople he was a chemist, asking whether they know of a lad would could serve as his apprentice. I suggested Rotter’s youngest, Jason, and the old man asked me what he was like. I said he was strong, healthy, smart as a whip, prone to hold a grudge, but more-or-less levelheaded otherwise—and just the right age. I expected the old man to jump at the chance of having such an apprentice. But her merely snorted and said the lad he had in mind would be a dreamer, most likely thought a fool or a halfwit. And then he looked at me and said he’d heard I had such a son. When I told him I did, he asked if I would be so kind as to send you to him.”

Sean sat frozen, his spoon halfway to his mouth. Greta began to sob.

“The old man has moved into that cabin that’s been standing empty since Widow Nelson died,” Brent said. As Greta continued her sobbing, Brent waited for a reaction from his son.

Sean stared at his father incredulously. Had his fame as an idiot spread through the land? The bread chewed like paper in his suddenly dry mouth, and the stew to which he had been looking forward tasted like shoe leather. He leapt up from the table. “I will see him, Papa,” he managed to choke out as he backed away from the table. He dashed out the door, tears stinging his eyes.

Sean didn’t actually intend to go to see the old man. He instead entertained a vague notion of running away. Once outside, however, there was nowhere else to go, and, after wandering about aimlessly for some minutes, Sean found himself facing the Nelson cabin.

Through the open door the young elf could see movement. It took several minutes for him to work himself up onto the porch and call out a hello. Instantly, a face appeared in the doorway. The eyes, nose, and month were almost lost underneath a vast white beard. The face was attached to a body of indeterminate bulk, wrapped in a loose black cloak. Black robes showed underneath the cloak. The face was stern, lined as if from great effort or worry, but the mouth turned up at the corners and there was a twinkle in the watery blue eyes. “My name is Fangale,” he sated, as if to no one in particular, “and you are Shan, the son of the merchant, Brent and Greta’s adopted son.” He looked Sean up and down closely. He saw a handsome boy dressed in rough homespun, with thick golden hair and a look of intelligence in his violet eyes. Sean saw eyes that seemed to burn a hole in him. He flinched, as if stuck with twin daggers, and looked away slightly. As he nodded in acknowledgement, he noticed small silver loops in the old man’s ears.

“Good,” said the chemist. “If you’re not the one, you’ll just have to do. I expect to see you at dawn tomorrow. We have much to do. Be on your way, now. There are some things I must take care of tonight.”

Sean was flabbergasted and more than a little hurt. He had been judged, accepted, and dismissed with such speed that he had no change to say a word other than hello. “But—what’s your name?” he finally managed to blurt out.

The old man stuck his head back out the door. “I can see you’re not a good listener, but I can fix that, I think. From now on, you must pay close attention when I speak. Your life will depend upon it. I’ve already told you my name. You don’t remember it now, but it will come to you on cat’s feet when the clock strikes midnight. Now be off with you!”

Sean, astounded, left. He spent the rest of the afternoon in such a fog that he was blamed by his father for several mistakes that were entirely his own fault, the worst being he left a loin of red meat on a counter until it became covered with files, which were thick in that southern climate all year round.

That night at supper, Sean told his parents and Raymond of his encounter with the old man. He was unable to satisfactorily answer their questions, since he had been so summarily dismissed before he had a chance to find out the old one’s particulars.

“Will we be able to keep him?” Greta asked Brent after Sean and Raymond had gone to bed. “Will he still be ours?” Brent shrugged his shoulders. “I don’t know,” he said. He stared into the embers of the fire until long after Greta had gone to bed. Finally, as the clock was striking midnight, he stirred the glowing coals and joined his wife in troubled sleep.

Sean, ordinarily a sound sleeper, was unable to go to sleep. Occasionally he would walk to the window and draw back the curtain, looking in the direction of the late Widow Nelson’s cabin. He sat sprawled on a chair, resting his head on his hands and brooding. It was thus that sleep overtook him. He awakened must later in darkness, and managed to find his bed. Just as he pulled the feather comforter to his chin, he heard the large clock in the hallway strike the midnight hour.

Suddenly, there was a noise at the window. Sean sat bolt upright and almost screamed—but the frightening, dark shape pressed against the glass soon enough resolved itself into a black cat. The head turned toward in Sean’s direction, the yellow eyes blinked, and the cat was gone.

Sean was sure Fangale had sent it. Wait—Fangale! The old had said his name would come to Sean at midnight on cat’s feet—and it had! Sean was still puzzling over this strange occurrence when he fell asleep.

Book I, Chapter II

Chapter II

Sean was awakened before dawn by the soft touch of his mother. Startled, he sat suddenly upright in the darkness and looked wildly about. His sleep had been deep and troubled. “Shush,” said Greta, as he opened his mouth to speak. “I’ve merely come so you will not be late to see the wi—to see the chemist.” Her words puzzled Sean, until he remembered he was indeed to see the old man Fangale this morning. But his mother had started to call the old man something, stopping herself just in time. Wizard? Many chemists were masters of sorcery, weren’t they? And didn’t good wizards wear white robes, and bad wizards black robes? This one wore black. And then there was the business of the name on cats feet at midnight. Fangale!

Sean rose and dashed cold water onto his face from the porcelain-lined metal pan his mother had placed on the oaken stand by the door. Wizards! Sean had consorted with them only in his fantasies. Did the old man really know magic?

Sean had never met an actual sorcerer; now he might have to deal with a real, and, from the look of things, an eccentric one at that. He was convinced by now he was being apprenticed to a magician. Why him? Why Sean, the dull-witted boy? And how powerful was Fangale? Was he good or evil? What powers, strange or familiar, did he serve? How was his temper? Would he curse and abuse his apprentice, or would he treat him with kindness and consideration? One thing for sure, thought Sean as he spooned down a bowl of porridge sweetened with honey—if yesterday’s encounter was any guide, the white-haired old man would never tolerate his daydreaming and absent-mindedness!

Sean, filled with misgivings, kissed his mother and set out for Fangale’s cabin. “Perhaps I’m indeed slow-witted. How can I ever hope to amount to anything when I’m unable to do even the simplest things without making terrible mistakes?” He asked this out loud, drawing curious stares from other early risers.

Sean’s fantasy world seemed remote and manifestly absurd to him now that adventure had entered his life in reality. He approached the black-garbed figure that sat unmoving on the front porch of the Nelson cabin, drawing himself up to his full height, and doing his best to clear his wits. He was determined to give all of himself for once, both physically and mentally, in what he was sure was a last-ditch effort mounted by his parents to save him from a life of mediocrity and stupidity.

If Fangale was aware of Sean’s raging feelings, he gave no sign of it; he merely sat, watching the rising sun, which was just beginning to show above the low hills that lay to the east of the village. “Sit, boy, and watch the sun wake the land,” he said. “It’s one of the few real pleasures in life—and it’s free.”

Sean shifted his weight from one foot to the other. “If it’s all the same to you, sir, I’d rather begin. I’ve wasted too much time already, engaged in such trifles as watching the sun rise and set.”

Fangale turned his head to face Sean and cocked a bushy white eyebrow. His pale blue eyes regarded Sean silently. “Sit down, boy,” he said at last. “Sit down and begin learning. Timidly, Sean sat on the top step and waited for Fangale to begin teaching. Yet Fangale said nothing, instead merely sitting and watching the sun, which was now nearly risen. When it was a finger’s width above the horizon, Fangale had still said nothing. Sean started to speak several times, but each time managed to bite his tongue.

Fangale eventually said, “That was quite satisfactory. And it was not, as you think, a waste of time. It may have taught you any number of things.”

“Patience?” asked Sean. The wizard nodded. “Perhaps.” He sighed. “Would you consent to spend some time with an old man, lad? As an apprenetice of sorts?” Sean answered that he would.

“I knew you would. I’ve planned for some years to come here to see you and train you. I’d hoped to spend two years or more instructing you in the ways of men and elves and wizards, and teaching about this old world of ours. But I received world only this morning we’ve not as much time as I had thought.” He nodded briefly at the interior of the cabin.

Sean, peering into the gloom, saw a great dark figure stretched on a pallet in the middle of the floor. Fangale continued. “It may already be too late. Much will depend on you, Shan, Merchant’s son. My safety and yours, the well-being of this fine village of Blackduck, and perhaps the fate of the whole world—it all will hang on your honesty, ability, and courage.”

Sean stared unbelievingly at Fangale. What was the old man on about? What incredulous nonsense was he being fed? It sounded like something from his wildest daydreams!

Fangale smiled at him. “I know you’re skeptical about me, uncertain of my intentions toward you. There’s much to explain, and you’ll not like most of it. Therefore, I’ll start at the beginning, proceed to the middle, and finish at the end. I’ll ask you not to interrupt before I’ve finished, at which time you may ask whatever questions you wish. Is that agreeable to you?” Sean scowled, then nodded his head, and the wizard began his tale.

“To perhaps clear up a mystery of long standing, I knew your parents. Your real parents. Certainly you have realized you were of Elvish birth. It’s a heritage impossible to hide.” Sean nodded, thinking of his pointed ears. “Fifteen years ago a party of Elvish royalty embarked on a journey from their homeland, headed for the sea which lies far to the south. Their destination was Pyrrhis, a great city some three months journey to the south of here. They never arrived. When word came to the Elflands that the caravan had never reached its destination, a party was sent to search for it. Finally, they found what was left of the caravan. It had apparently been plundered and burned by thieves. The travelers had been murdered. The searchers returned with the bodies, which the exception of a two-year old, one Shan, who was not found.

“Preparations were made to mount a massive search for this youngster, but internal problems in the Elflands—specifically, the warring of various factions—delayed these plans several times. Finally they were dropped, since an abandoned child would have quickly fallen prey to wolves or orcs or to the great cats, or else succumbed to the elements.

“The internal strife in the Elflands came about because the Elvish king and queen were among those murdered in the caravan. Without the stabilizing influence of a ruler, without even an heir to the throne, petty grievances which had simmered for decades quickly escalated into armed conflicts. The child, Shan, was of enormous political importance because he was the only child of the king and queen, the last of his line. Any party who held him could claim stewardship to the throne until he matured and could assume his kingly duties.

“Needless to say, if Shan had fallen into the wrong hands, he would have spent his formative years staring at the inside of a prison cell while the Elflands were governed in his name. He would never have seen adulthood; some time before his majority, he would have succumbed to a carefully planned and executed accident or illness.

“Wise heads, realizing this, decided to seek the services of an old friend of the elves, a sorcerer who had served them often and well. They summoned him and, when he arrived, asked him to seek out the child—if, indeed, he were still living. They thought if he hadn’t been taken captive by the robbers who ambushed the caravan, there was a remote chance he had been found by the humans who lived nearby.

“This wizard—whose name, as you may have guessed, was Fangale—began making queries about the child Shan through a long-established system of contacts. Within a year he had located the child, but by then things were so bad in the Elflands that he dared not report he had found the prince. He kept the news to himself, watching as Elvish politics ran their course and the elders—all of them—were murdered or discredited and removed from positions of authority, at least, those who didn’t have the sense to flee. They were replaced by a steward appointed by a hastily-convened board of elders. Boro was to govern the land until the time the prince showed up to claim his throne.

“After about a year, Boro had his puppet board of elders executed, pronounced the prince dead, and tried to assume the kingship. He would have attained his but for the populace, which threatened revolt, for I had planted rumors the king would return on his eighteenth birthday and claim his throne. Most of the Elflanders believed this tale, and Boro feared revolution if he proclaimed himself king. Therefore he announced he would remain as steward until the prince, if he were living, would have achieved his majority. If he had not returned by then, a free election would be held and a new king—Boro, you may be sure—would be elected.”

Sean started to speak, but thought better of it.

“The election is scheduled for next spring, on Mayday, the eighteenth birthday of the prince. All indications are it will be no more free than a river is ‘free’ to flow upstream. Boro has had many years to consolidate his power and arrange things so he will win the election and become king. He has turned the Elflands into a police state.

“Though all these years the retainer concealed the existence of the prince from everyone, and of himself from the prince, waiting for the right time to arrive. Then he would go to the prince, tell him of his true identity, and go with him to the Elflands, where he would assume the duties of king.

“Now to be sure, this would have been a difficult and risky undertaking, for the steward Boro would not have given up control without a fight. The wizard, however, was not without his resources; he was sure he would prevail.

“Once the prince was installed on the throne, I—that is, the retainer—planned a course of teaching and training for him. And then he planned to ask a great favor of the new king.

“And that was the plan. Of late, however, there has been much evil set loose in the world; this is true not only in the Elflands, but everywhere. And because of the evil tidings I just received, it has become necessary to change my plans.

“After training the king, I had planned to ask you—that is, him— to do something for me. It would have been hazardous, but by no means impossible, and with his special training, the young king would have had a good chance of accomplishing it. Yet now I must ask the untrained prince to undertake this same quest. A journey is involved—a long one—and it is fraught with peril. There is little time now for training, and because the nature of the task has changed, he would be in danger even if he were a master of weaponry and tactics. He is unlikely to survive. And even if he isn’t killed, chances are while he is gone his eighteenth birthday will come and go, and his kingdom will be forfeit. If by some miracle he survives, it would be only to return to find himself dethroned and his land thrown into disarray and corruption.

“And finally, I had planned to be at the prince’s side every instant, but now I find I have other duties. I will do my utmost to be with him at critical times, but I cannot be counted upon to be there in times of trouble. I may myself be killed, for my tasks are also dangerous.

“If the prince should agree to embark upon this mission, he must understand accept he will in no way profit from it. It will rob him of his kingdom, his recognition as heir, and perhaps even his life. Any reward must be intrinsic, for he will not gain in wealth, power, or fame from the quest—although, if he survives, he may profit in terms of experience and maturity. His reward must come from knowing the fate of the world was in his hands and that against overwhelming odds, he almost singlehandedly saved it. Yet if he tells this to others, they’ll not believe him and will beat him with sticks and call him a liar.

“Perhaps the prince would be a fool to accept the mission on those terms. Yet it’s my plan to beg him to consider undertaking it.”

Fangale regarded Sean, who had was sitting silent and white-faced. He was feeling needles and pins prickling at the base of his neck. Now the old man stirred and spoke again. “Would you consider, for the sake of the salvation of the world and an old man’s gratitude, undertaking a quest for me?”

Sean extended his forefinger slowly, looking at it as if it belonged to someone else, and turned it to face his own chest. “Yes,” said Fangale. “Yes, Shan, Prince of the Elves, also known as Sean, Merchant’s son, will you undertake this quest for me?”

Book I, Chapter VIII

Chapter VIII

As it came from the northlands, flying through the night on leathern wings, the stars wavered, foul winds blew, clouds gathered. Southward it flew towards its destination, over tundra, over snow-capped peaks, over dark forests. It hated as it flew over grounds it had wasted— hated Smendra, who had brought it to this loathsome place, hated the flying creatures of the night which dipped and swooped madly in efforts to get out of its way. It hated the sunlight—it hated the sun most of all. It hated, hated, hated, as it flew southward, to the servant of the Dark Lord who had summoned it.

Sean was sleeping soundly when he heard an eerie scream in the night. The scream had an inhuman quality, and some sixth sense warned him it came from no living throat. As he listened, wondering what had wakened him, Sean heard the call again; it was nearer. And then he saw the Left Eye. The emerald in the hilt was glowing softly. Sean felt an unexplainable chill in the room, and wondered if the fever was returning. Outside, all was black, as clouds moved across the moon, and a northern wind was rising. Quickly, Sean pulled on his shirt, britches, and boots. Stooping, he knelt to pick up his pack from the floor beside the bed. As he reached for his cloak, for it had become very cold, the roof groaned above his head, as if something massive had landed there. Sean reached past the cloak and grabbed the Green Sword instead. It was warm to his touch, and the emerald glittered and pulsed. He moved backwards as a rustling, scratching sound began right above his head. Suddenly, the ceiling splintered, and a clawed limb of awesome proportion crashed through into the room and flailed about wildly, searching for him. Yellow talons on the ends of the fingers sliced through the air barely an inch from Sean’s chest, and he jumped back as the limb moved about, cutting off his route to the door. Meanwhile, a great hooked beak tore wildly at the roof, enlarging the hole.

To hesitate was to die. Sean saw but only avenue of escape. He took a deep breath and ran full-tilt at the window. He crashed through it, his arm thrown before his face to protect it. Broken glass scattered in all directions, but miraculously, Sean was not cut. He landed on the roof of the back porch, feeling a sharp shard enter his back as he rolled, and went over the edge of the porch onto the ground. Instantly, he was on his feet and running as fast as he could for the nearest thing he saw, which was the massive wall that surrounded the town. Behind him he felt, rather than saw or heard, the unspeakable thing launch itself into the air from the roof of the house, and he knew it was coming straight at him. But he reached the wall and scampered up a flight of narrow stairs, hoping to reach the catwalk that paralleled the top of the wall. As his chest reached the level of the catwalk he felt the stairs smash under him as they were hit by the creature. He was left with his feet dangling,a nd as he pulled himself onto the catwalk, he envisioned slavering jaws grindings his legs to pulp. And then he was over the wall, handing into the blackness on the other side. He dropped just as the wall buckled. He hit the ground below, scrambled to his feet, and raced into the night. Behind him the creature finished smashing its way through the wall. Glancing over his shoulder, he could just make it out, pursuing him this time on the ground, coming in great leaps. He had about a hundred yards lead, but the creature was gaining fast. And then Sean remembered what Fangale had told him about Manukan. “Although the Left Eye, which you carry, cannot by itself directly harm Silarith, it may be able to aid you in other ways. I cannot predict when or how Manukan will help you, but when all seems lost, grab the hilt of the sword.”

Sean was holding the Left Eye by its middle; his knuckles were white on the sheath. As he ran, he grabbed the hilt with his free hand. The emerald visibly brightened. He could feel the heat of the creature’s breath, and knew it was upon him. Surely it was Silarith! “oh, help me, Manukan,” Sean cried.

Just as he was sure he was about to be struck down from behind, Sean was hit by a blinding curtain of rain. He was wet instantly. So heavy was the rain it was difficult to breathe, and it was impossible to see even an inch in front of him. Sean dodged to the right, continuing to run, slipping and falling in the sudden mud, the water up now to his ankles, now to his knees. For twenty minutes he ran, weaving an erratic path in the night, and the rain fell with a ferocity he would not have dreamed possible. He knew the fear one knows only when death can strike suddenly from nowhere, but there was no sign of Silarith.

At length, Sean ran full-tilt into the trunk of a tree. It knocked the breath from his lungs, and he lay gasping for a moment before he dragged himself to his feet. He proceeded at a trot now, through a wood, his hands before him to fend off low branches. Finally, the rain slackened to a drizzle and then stopped. He fell, drenched and exhausted, onto a thick bed of pine needles underneath a tree with thick, overhanging branches.

Book I, Chapter IX

Chapter IX

As Sean lay gasping on the soft needles under the tree, he heard the dry, raspy sound of Silarith’s huge wings. They were approaching from the direction in which he had come. The monster had again taken to the air. At first he was sure the creature could somehow track him, and would soon be upon him, but he didn’t run. He lay silently under the tree.

Silarith seemed to be circling, looking for some sign of his prey. The sound and smell of him passed close overhead, and then diminished in to the distance, only to grow louder again as the monster circled to Sean’s left. For some time Silarith searched the wood, but finally, screeching his frustration to the night skies, he flew off towards the north.

Within minutes the thick clouds which had obscured the moon and stars disappeared, blown away by a warm breeze from the south. Sean rose from his hiding place and took off his clothes. He shook loose pieces of broken glass and then wrung the worst of the water from his homespun shirt and britches. The water from his boots splashed gleefully on the branch of a tree. Sean could feel something sharp in his back; reaching with one hand, he managed to pull a splinter of glass from his skin. He then put his damp clothes back on and looked about. The thick branches of the evergreen trees cut out much of the light form the moon and stars, but Sen could see patches of pine needles here and there where moonbeams reached the ground. There seemed to be a path to his left, leading further into the wood. Wishing to put as much distance as possible between himself and Sandsville, Sean set out cautiously in the darkness. After he had tripped several times over roots, he decided to cut a walking stick. He reached for the knife which he had carried in his belt, but it was no longer there. The last he remembered seeing it was when he drawn it while hidden under the rock, in order to defend himself from Rollo the highwayman. Probably, he had lost it in his delirium. The pack containing his extra clothes and his food was on the floor in the house of Orin Sands, where he had dropped it as he leaped for the window. He searched his pockets for the leather pouch which contained his gold pieces, but it was gone also. He did locate two pieces of silver in a pocket of his pants; at least he could buy one good meal! “If ever I manage to reach a place where I can spend it,” he thought grimly.

Sean found a small tree which looked as if it would make a suitable walking stick. But when he picked up the Green Sword to lip it off, he felt a sense of great anguish. The pain rushed up his arm and made him jump backwards when it reached his brain. He had to sit on a fallen tree until the sense of weariness and pain had subsided somewhat. He remembered Fangale had said Manukan could aid him only at great cost to himself, and reckoned that when he had grabbed the sword, he had felt a small part of Manukan’s pain. The emerald shone only dully. He replaced the sword gingerly in its sheath.

It took him fifteen minutes to break the tree. Finally, he had to walk around and around in a circle to twist the last shreds of bark off. As he made his way through the forest, occasionally straying from the path and having to find it again in the gloom, Sean though bitter thoughts. Some way, somehow, the creature Silarith had located him at the house of Orin Sands. It had known just where to find him. Yet later, while he lay trembling under the pines in the forest, it had cast about aimlessly for him. Surely someone had told the monster of Sean’s whereabouts, someone who had known his identity. He had been betrayed! But by whom?

Hard as it was to believe Wendy had given him away, Sean knew none other who could have known who he truly was. As difficult as it was for him to bear, the finger of guilt pointed squarely at her. It was a grieved and cynical Sean who made his way through the forest that night. One part of him refused to believe his Wendy, with her sweet face and gentle manner, could possibly have turned against him. Yet another, albeit a small part of him, said, “Yes, it was Wendy! She has betrayed you, used you, was laughing at you as you made such a fool of yourself, professing your love.”

Through the night Sean walked, never stopping to rest. His thoughts were as bitter as acorns. Eventually his clothes dried with his exertion, and, as he still felt strong and healthy in body, his fear he would fall ill because of the soaking subsided.

Sean walked all that day, with nothing to eat except for a few berries he found on a busy. He slept that night in a hollow tree. His grumbling stomach didn’t quite keep him awake. He awoke in the middle of the night, feeling refreshed, and decided to press on.

The night was still with the promise of dawn when Sean noticed the forest had begun to thin. Soon the trees, standing tall and straight, were regularly spaced, as if in a park. The path widened, and under his fee now where only soft leaves rather than roots and hidden fallen branches. Had Sean not been human-raised, he would have realized he had entered the Elflands. He strode across graceful wooden bridges which spanned burbling streams and passed houses carefully designed to blend into their surroundings. His inner conflict caused him to be oblivious to it all. He was giving little thought to where he was going. He realized dimly he must have entered the Greater Dank Forest and should proceed eastward along the path until he had the opportunity to ask directions to Genre. So he was quite surprised when suddenly a stern voice demanded from somewhere in the darkness, “Halt! State yer name and busy-ness, stranger. Do nut moof and do nut ryach fer a wyapon or yu will nyuver liff ter see the dyawn!’

Sean dared not even turn to face the unseen voice. He said, “My name is Sean. I am traveling along. I come from the Southlands. I am bound for the town of Genre. I am unarmed, except for my sword. Is this Genre? Have I arrived?”

“I’ll ayust the qyestions,” replied the voice, which had moved somewhat closer. “Hold styull.” Sean felt hands remove the Green Sword from his waist, then pat him on the torso, arms and legs, searching for concealed weapons. When the hands stopped the voice said, “Very wyull, you may tyurn aboyut now, but keep yer hyands in plain viyuiew.”

Sean turned to face an elf. He was surprised to find the Elflander was no older than me. The elf looked him closely in the face. He looked down at the sword in his hands, started, and looked more closely. He half-closed on eye and looked at Sean quizzically. Suddenly he grinned. “Jyoost checking.” He handed the Green Sword back to Sean. “It’s not usyual fer travelers to be aboyut after duyark. Thar are beyars and woyulves, and other creatyures which can be oonpleasant and even fatal if encoyuntered unexpectedly. Not even to mention gayungs of royubbers. You’re brayuve to trayuvel alone, must lest in the duyurkness.”

“I had no choice of when to travel,” said Sean, “for highwaymen made the choice for me. I had to be on my way or else fall victim to them.”

“Oh,” said the other. “That ceyurtainly explayuns that. You must be tiyurd and perhaps hoongry, my friend. I’ll wayulk you to the viliyuge, if you like. It’s not far. The niyut is aboot over, and my reliyuf had joose arriyuved before you showed up.” The young sentry nodded at a second elf, who Sean had not noticed before. The second elf stood far back in the shadows, an arrow nocked on the string of a longbow. “It’s all reet, Tobiah,” called Sean’s escort. “He seyums to be a trayuveller who was seyut upon by royubers in the niyut.” Tobiah obligingly returned his arrow to his quiver and raised his three-cornered hat to Sean. Sean, who was bare-headed, nodded back.

As they walked down the path, the sky beginning to brighten, the young elf introduced himself. “My nayum is Milrond.” He prounounced it “Miyulrond.” “The villiyage we are coming to is called Tosc.” Sean, by first light, began to make out buildings on either side of the path. The structures were made of wood, skillfully constructed so they were almost possible to see unless one was close. Here and there an early-rising elf could be seen setting about the day’s labors. Milrond guided Sean to a house which was a little larger than the others. Stepping up to the door, he knocked sharply, and immediately a silver head popped out of a window. Milrond said, “We have a strayunger heyur, who sayud he was on his way to Genre when he was set aboot by royubers. He apeayers to have loost all of his possessiyuns, and would probably aproociate a hot breyukfast. I’ll leave him with you, fer I’ve been on patroyul all night and am anxious to get some sleep.” So saying, Milrond tipped his feathered cap in Sean’s direction and disappeared into a nearby house.

The silver-haired elf opened the door and motioned for Sean to enter. Sean did, and was truck by the smell of breakfast cooking. The heavy odor of bacon was mingled with the scent of buttermilk biscuits, and he smelled the pepper as an elfess, a matronly woman with gray hair and wearing an apron embroidered with flowers, ground some from a mill onto eggs sizzling in a pan. She turned from the stove in order to smile briefly at Sean, and hen went back to the cooking.

The oldster closed the door as Sean stepped past him, and extended his hand. “My mane is Rolondo,” he said, “and that’s my wife, Yallo, at the stove. I’m the mayor of Tosc, this small but exceedingly pleasant village.” Despite his apparent age, his voice was firm and strong, and so was his handshake. Having just arisen, he was dressed in a maroon robe. A network of fine lines covered his face, but his eyes were blue and steely. “Won’t you have breakfast with us, and tell us the news of the place from which you have journeyed?” He made a chair screech as he pulled it back from the table. Sean mumbled something about having little money.

“Nonsense, exclaimed Rolondo, making a motion towards the chair. “You’re my guest, and guests don’t pay in the Elflands!” Sean sat, and soon was eating the delicious cooking of Rolondo’s wife. Yallo insisted Sean eat second helpings, and then thirds. He finally balked when she tried to coerce him into eating a fourth portion.

“I couldn’t possibly eat another bite,” he said, “although it’s the most delicious cooking I’ve ever tasted.” Yallo blushed. When the meal was concluded, Rolondo determined Sean had come from the south and began asking questions. Sean told him the rumors that he, being an inhabitant of a small village, had inevitably heard. Finally Rolondo, satisfied, reared back in his chair and lit a pipe.

“We rarely get news here in Tosc,” he lamented, “since few travelers pass this way. So when someone does pass through, he ask them all sorts of questions, for we may receive no more news for months on end.”

Sean marveled at the mayor, so friendly and generous to a stranger. With his new-found skepticism about all things, he considered briefly whether Rolondo might not be the pleasant old man he seemed. But his gut feelings were the old man was as he seemed, an aboveboard and honest fellow. At his deepest levels, Sean still smarted from Wendy’s betrayal.

“Milrond said you are journeying to Genre,” continued Rolondo.

“That I am,” said Sean, not sure he had been right to be so open about his destination. “But I have no idea where it is.”

Rolondo gestured with his pipestem. “It’s in that direction, about a day-and-a-half’s journey on foot. But’s possible to travel the distance in a day, if one walks fast and rests but little. It’s a fine walk as long as this pleasant weather holds. About midway is a village named Tortuna, where bed and breakfast can be bought cheaply.”

“Thank you,” said Sean. “What path should I take?”

“Merely follow the path on which you came. It will end in Tortuna, where you must turn left… or is it right? Oh, dear. Left, I think. Yes, I’m sure it’s left. You might ask further once you reach Tortuna. My sense of direction isn’t what it once was.” He shook his head sadly. “Will you be staying for the night? There’s an inn in the village.”

Sean said he planned to press on. “Thank you for your concern,” he said truthfully, for he had reluctantly decided the old elf was being helpful and not scheming against him in some manner. “But my business is such I stand to lose a great deal if I’m not prompt. Yes,” he continued, amused by his own wit, “a very great deal.”

Rolondo indicated he understood. “Very well, but I counsel against entering the capital city at night.”

“Why?” asked Sean.

“They’ll likely lock you up, that’s why,” replied the old mayor, with a shake of his head. “Things aren’t as they once were in the Elflands. You’ll see the influence of the Steward Boro grow as you approach Genre.”

“What do you mean?” asked Sean.

“Just look at the faces of the people,” Rolondo said. “Look at the faces of the people, and you’ll understand.”

Book I, Chapter XVI

Chapter XVI

For a long moment Sean managed to stifle his sneeze. His nose burned mightily. He rubbed his finger vigorously along his upper lip. This worked to some extent, but the urge to sneeze gradually grew stronger and stronger, and finally the narrow confines of Sean’s barrel resounded with the pent-up explosion. Then the top of the barrel was yanked off, and Sean knew he was discovered!

But the face into which he stared belonged not to Silarith, but to a man wearing a white chef’s hat. “And what have we here?” he asked sarcastically. “Why, I do believe it’s a morsel for the royal table.” He tipped the barrel, spilling Sean out onto the stone floor. “Now, my merry gentleman,” he said to the flour-covered elf lying in front of him,” who are you and what are you going here? Speak, or must I call the guards and have them shake it out of you?”

“Don’t do that!” exclaimed Sean. “I have come here to seek work.”

The man looked down his long nose and snorted. “We don’t get many elves around here. You’re the first I’ve seen in ages. And look where I found you! An unlikely place to find employment, I should think in the bottom of a barrel. Did you think you would earn many wages in there?”

“No sir. I hid when the curfew bell sounded. I come from far away, and it was late when I got here. I have no money and no place to stay. So I climbed into this barrel, as it was as cheap a place as any, if more cramped than most.”

The cook grinned. “I like your wit,” he said, “although I can’t say as much for your appearance. You look like an unbaked biscuit. What do you know of cooking?”

“I can keep myself fed,” replied Sean, “by warming food over a fire, but I must admit I know little about mixing things together so they are fit to eat.”

“Good,” smiled the cook. “Then you will have less to unlearn. You may work for me today, and, if you perform satisfactorily, I will take you for apprentice. I am in charge of the kitchens today.”

“Then you are called Pianato,” said Sean, remembering the name the guard had spoken.

The cook scowled. “No, my name is Cato. I am in charge because today is Sunday, and Pianato and Taro and Bixby and Lanny and Fitch wish to lie late abed.” Cato’s chest swelled visibly. “I, you see, am the sixth cook. That means that when everyone else is having a holiday, guzzling wine, dancing with girls, telling lies, I am here in the kitchens, telling the apprentices to do this and to do that.” Cato’s chest went back down. “And when there is a great feast, which special meals are to be served, when there are guests, I must scurry with the apprentices, fetching and carrying for Pianato and Taro and Bixby and Lanny and Firth. Sometimes I think,” he sighed, “I took up the wrong trade.” He brightened. “But from now on you will be my sixth cook. But what will I call you? You must have a name. Out with it!”

“Barry,” lied Sean. “My name is Barry.”

“Well, then, Master Barry, come with me. There is a large pile of potatoes asking to have their skins removed. We’d best hurry, for the sun will be up soon.”

All day long Sen worked like he had never worked before. Cato was not a cruel master, but he kept Sean busy, allowing him to stop for only a few minutes to eat meals. “Ah, but you’re eating the same thing the king is eating,” he exclaimed. “Even if much more rapidly.”

Sean almost choked at this. He had been wondering all day how the poison was given to the king. Perhaps he was being poisoned even now. It was possible Cato was the spy who had talked to Silarith early that morning. But for some reason Sean didn’t think so.

The other apprentices eyed Sean as they trickled in, but Cato kept them much too busy to converse among themselves about the new addition to the kitchen staff. Sean worked steadily, ignoring them, as breakfast, and then lunch, and then supper were served. Each time there was a mountain of dishes and pots and pans to be washed, and each time Sean was told to scrub them. He spent most of the day at the sink, and his hands grew white and wrinkled. Each time he had nearly emptied the sink, an apprentice would gleefully dump another cartful into the water. Sean decided kitchen work was never ending. Whenever one finished cleaning up from the last meal, it was time to prepare the next!

But, inevitably, there came a time when the last pot had been washed, dried, and put away, the last apprentice sent home. Sean found himself alone with Cato in the kitchen. As Cato sat on a stool and watch him mop the floor until it shone, Sean questioned Cato. “They say in the farmlands and in the mountains that the king has imprisoned his own son. They say Berryl slew his brother Randall.”

“Some do say that,” agreed Cato, “but many more believe things happened as Berryl said, that Randall was slain by orcs in the Northlands. Randall spoke of such creatures before he left. And Berryl always worshipped his brother. Berryl used to hang around the kitchens when he was a youngster. He was interested in how things work, and why things were the way they were rather than any other number of ways they could be. When he grew a little older, he was always more interested in the lasses, or in testing out a new weapon, or in one of his pranks or adventures than he was in matters of state. He did not want to be king, and I don’t think he slew his brother. Neither do the majority of the good folk of Neador.”

“How can the king be so harsh on his own son?” asked Sean.

“Some fear the king is under the influence of his advisor, Menchant.” Cato spat on the clean floor. “He’s an evil one, and that’s for sure. Menchant came to Neador about a year ago. In no time at all he had endeared himself to the king by flattery. King Nathaniel cannot see through his guile and insincerity. As soon as he could, Menchant fired or imprisoned the king’s most loyal guards and filled the ranks with his own henchmen. The king seems to be coming more and more under his influence There have been many other changes, and not for the better, in the way the kingdom is being governed. The king seems to be in a daze, appearing befuddled and bemused. But none dare speak out against Menchant for fear of their own safety. I saw Menchant skulking about early this morning. He was probably up to some of his mischief!

“Now we’d best be going to our quarters,” continued Cato, “for we must work again tomorrow.” He led Sean out of the kitchen area, down endless halls lit by the feeble glow of torches. “Always follow the green line,” he said, referring to faded colors painted on the floor, “and you will find your way to the kitchens. The purple line will lead you to the royal chambers, the white line to the servants’ quarters, where we are headed, the brown line to the stables, and the red line to the front entrance of the palace.”

“And the black line,” inquired Sean, “where does it lead?”

“To the royal dungeons,” replied Cato. “Now walk faster, for I am very sleepy.”

Just before Sean and Cato reached their quarters, Sean heard female laughter coming from beyond closed doors. “Who is in there?” he asked.

“That is the quarters of the female servants,” answered Cato. “Don’t ever go in there, for they will scream and throw things at you. I wandered in there once and was lucky to get back out alive!” Sean laughed.

Shortly, they arrived at Cato’s lodgings. Cato’s apartment was narrow and long, sparsely furnished with a bed, a dresser, and a desk. “They say years ago the captain of the guard once lived here,” said Cato. “As you can see, I live simply.”

Sean wondered how he occupied himself, if, indeed, he had any after his work in the kitchen was through. Cato pulled a brass key from a drawer of his desk and opened a door in the right wall of his apartment. Inside was a very small room, about eight feet square, in which were stacks and stacks of paper, all written upon with a curious hand Sean suspected was Cato’s. He helped Cato clear the room, piling the paper in a clear corner of Cato’s room.

Eventually a small cot was uncovered. “You may sleep in here,” Cato told him, lighting a candle and setting it down on a small table. He then closed the door, leaving Sean alone in the room. Sean gave a perfunctory inspection to the strange room. Except for a loose flagstone in the floor, it seemed satisfactory. He lay down on the cot, covering himself with a pale blue woolen blanket. Although he had hoped to spend time plotting and planning the escape of his friends from the dungeon, he fell promptly to sleep.

In his own room, Cato dipped a quill into ink and scribbled furiously on a sheet of paper. As he added another recipe to the stacks of paper on the floor,” he sighed, “Oh, to be first cook! To be able to actually try my fine recipes!”

Book II, Chapter I

Chapter I

For five years now in the Northlands, the sun had not come with the springtime. The land was black, for ugly clouds cut off the dim light of the moon and stars. The caribou had long ago left, traveling southwards in search of forage; they had not returned. After them went the wolves and the fur-clad people who hunted the caribou for meat and ides. Occasionally lightning from the everpresent thunderstorms that plagued the land would light the bleak landscape for a brief instant, to show bare rocks from which strong winds had swept the last lichen. All the Northland was a vast, silent desert.

There was a great castle amidst this desolation. It was said in Neador, far to the south, that no one had ever seen it and lived to tell of it. This was not so, for one brave man had entered it and tried to escape to warmer lands where the sun still shone. This had not pleased the master of the castle, who sent his terrible winged servant to search for him from the air, and a party of his lesser servants to track him on horseback. Yet all of his servants had failed; the one called Randall had told the Dark Lord’s secrets to his friend before he had died. Furious, the master of the great keep, which was called

Neverhome, had those who had failed to stop Randall flayed alive, except for the winged one, who was technically alive and therefore could not be slain, although it could feel pain. The creature, Silarith by name, had suffered cruel punishments from its dark master, Smendra. It raged and screamed in hatred for its master, but could not harm the man who had released it from the pentagram which had imprisoned it, for Smendra controlled the creature with a powerful magic spell. Only when it was back in its own plane of existence, or trapped within a pentagram, a network of lines which temporarily bridged the gap between its native plane and the one it now inhabited, would it be released from control and act once more on its own volition. If the creature had hated and despised Smendra before, it loathed him after suffering nights of isolation in a room filled with bright lights.

And then Smendra had become aware, through the eyes and ears of one of his servants, of one who posed a great threat to him. He cursed the ineptness of those who had foiled their mission more than a decade previously, letting the infant prince Shan escape through oversight or carelessness, even though they had killed both his parents. He had hoped the elf Shan was dead. This latest menace took priority over the old fool Fangale, and the winged one was again sent through the night on a mission of murder. And he had failed again, and again was punished. From under the very nose of the winged demon the young elf had vanished. Nightly, Smendra’s servants scoured the land for Shan, and Smendra’s eyes and ears, his puppet servants, also searched the plains. Yet the elf was not found.

The Dark Lord was pleased when his servant Menchant, who willingly schemed for Smendra for the power Smendra could give him, said he had succeeded in talking the weak King Nathaniel into imprisoning his son Berryl. Berryl had learned the dark lord’s secrets, and must die. He sent word back to Menchant to have Berryl killed at the first opportunity. Smendra was even more pleased when he received news the dwarf Serath and the Neadorian Brandon were also in chains; he ordered them put to death also. But when word came Berryl, Serath, and Brandon had escaped, and Menchant had let the Red Sword slip through his fingers, Smendra ran amok in Neverhome, causing walls to tumble and storms to rage in the surrounding countryside.

Yet the gathering of Smendra’s armies was proceeding faster than scheduled. Orcs, stupid, hairy half-men, susceptible to control by Smendra’s vast mental powers, had come in countless numbers, as had thousands of humans eager to fight for power or glory or wealth. Smendra knew it would be only a matter of time before his demon ran the young prince Shan to the ground, and then his Elven blood would flow red enough. Although Sean could theoretically harm Silarith, he was too young and inexperienced to do so in actuality; of this, Smendra was certain. The Dark Lord smiled and twisted the gold ring which encircled his right index finger. Soon he would be able to keep Silarith in this dimension twenty-four hours a day. He would have his enemy yet.

Book II, Chapter II

Chapter II

Five weary travelers rode into Dwarfhome in the middle of November. Once, an elf; wore at his side a sword of marvelous design. A second, a wizard dressed in black robes, looked enormously old, his eyes filled with a sorry that suggested the tragedies he had seen in his long years on the earth. A third carried himself with the regal bearing of a prince. An empty leather scabbard slapped against his side as he rode. The fourth wore his name, Brandon, embroidered in crimson thread on his sash. The fifth wore clothes as ragged as a beggar’s but carried himself nobly. He was well-known to all the dwarves, who ran to bade him dismount so they might embrace him. He was a dwarf himself, and those who knew him called him Serath.

“Ho, Serath!” “Have you ridden long and hard? Your horse and your clothes suggest this is to.” “Do you bring news from the Southland?” Serath begged to be allowed to tend to his horse and friends, saying he might be found directly in the great hall of the Hungry Horse tavern, where he would hold out at length on any subject chosen for him, as long as his whistle was kept wet.

The riders tied their horses outside the Hungry Horse. Fangale tossed a silver piece to a youngster, telling him to lead the steeds to a stablemaster and have them rubbed down, fed, and watered. Although the travelers looked as if they, also, could have stood food and drink, the wizard led them not into the cool interior of the Hungry Horse, but rather directly to the house of Loki, the headsman of the village, and asked for an audience.

Fangale knew Loki well. The dwarf, whose red beard was streaked with white, and whose belly protruded well past his belt, greeted the wizard warmly and bade him sit. Fangale did so wearily and introduced the others, except for Serath, who was a cousin of Loki and needed no introduction.

“And what news have you, Fangale?” asked Loki.

“The dark powers of the Northlands prepare to wage war on those further south,” replied Fangale. “Your village will be among the first attacked when Smendra’s hordes pour from his stronghold.”

Loki frowned and paced the floor. “I’ve heard rumors of this. yesterday a rider appeared, a human, a giant even among his own race. Trace was his name. He made signs that told he was your messenger, then bade us prepare ourselves for attack. We’ve begun to do so.”

“Trace!” exclaimed Sean. “Is he still here?”

“Yes,” replied Loki. “He has taken lodging at the Hungry Horse.”

“I’ll go and fetch him,” Serath announced, and promptly left. Within minutes he was back with the giant. Trace’s face brightened when he saw Berryl. “My prince!” his eyes seemed to say. He turned to Fangale and handed him a piece of parchment.

Fangale read silently from the paper. “Good,” he replied. “What was the reaction of the peoples of the Southlands when you told them of the danger that faces them?”

Trace shook his head sadly and pointed to a spot on the parchment. Fangale read, “The halflings have begun training a militia, and they offer their help, but I’m afraid they will be so slow in organizing that we cannot count on their help. The Steward of the Elflands has stated the elves have no grudge against the Dark Lord, and has hinted Smendra can look upon the Elflands as an ally. The elves from some of the villages in the fringes of the Elflands are heavy with rumors of the return of their prince, and have offered the swords and bows of all their adult males. There will also be help from the elves of Sandsville.”

“And the humans?” Fangale prodded. Trace pointed to a spot near the bottom of the parchment. Fangale read, “The humans either scoffed or made excuses. It has been so long since they have known war they do not believe such a danger possible. They will not be alarmed until the enemy is upon their doorsteps, and then it will be too late.”

Fangale turned to Loki. “And what of the dwarves?”

“The dwarves will fight!” said Loki forcefully. “Our troops will be at your service, Fangale. We are more ready than most, since we’ve long fought stray tribes from the Northlands. We can be ready to march with but several days notice.”

“Excellent!” cried Fangale. “You are a true ally, Loki!” Loki produced a bottle of brandy from a cupboard and proposed a toast. “To the end,” he said, raising his glass high, “whether it’s the end of Smendra or the end of civilization, let us drink to it.” The others raised the glasses which Loki had filled, yelling, “To the end!” Downing their liquor, they smashed their glasses on the stones of the fireplace.

That evening, the six adventurers sat in the Hungry Horse, elbows on the dwarven oaken tables, flagons of ale before them. Trace seemed the most uncomfortable on the undersized benches, which were made for dwarven anatomies, but he did not complain. Buxom dwarven wenches came and went, bringing more ale, platters of food, or stopping merely to joke with Serath, who appeared to be having the time of his life. All afternoon he hat sat in the tavern, laughing and talking with the young girls and impressionable young dwarven men. Only Brandon had out-drunk him and out-wenched him in the past, and Serath was determined not to let the same happen in his home town. Brandon seemed somewhat somber, which was a change from his usual carefree self.

Eventually, Sean was pressed to re-tell the story of his adventures. He did so, omitting nothing. All listened in amazement as he told of the night he spent in the flour barrel, and of the conversation he had overheard between Menchant and Silarith. Berryl swore under his breath when he heard again of Menchant’s poisoning of his father. When Sean told of his entrance to the dungeons in disguise, wearing the dress of a woman, all laughed. “A clever idea, to be sure!” exclaimed Loki. Sean’s companions nodded sagely as he described pushing the guard into the blackness. His hand flew to a scab on his neck as he described encountering the guard outside Berryl’s cell. As Sean finished his story, Serath proposed a toast to the young elf. Serath was slurring his words a little, but was able to say, “Sean, you may be only seventeen years of age, but already you’ve been through more danger than most men see in their entire lives.”

“That is true,” said Fangale. “Sean, I’ve had little chance to tell you this,k but I’ve been pleased with you. A person with less mettle would have perished before this. Here, full of good ale and delicious food, surrounded by his friends, he was happy. His heart sang with love for Wendy, now he had Fangale’s assurance that she had not betrayed him. He felt the world was not such a bad place after all.

Long into the night the drinking and talking continued. Yet far to the west the demon Silarith circled, eyes on the plains below, looking, always looking, for a young elf with a sword with an emerald set into its hilt.

Book II, Chapter X

Chapter X

Sean woke to utter darkness. A large and hairy hand was clamped firmly over his mouth. But if it was blackness, it was certainly not silent. Somewhere nearby Silarith screamed. It was a sound to curdle the blood. Sean hoped it wasn’t a victory screech, and that he had not already been torn to bits by the beast. Perhaps he was indeed dead. But if he was dead, why was a hand covering his mouth? Guessing the hand might belong to one of his friends, he patted the arm to which it was attached, indicating he would be silent. The hand was removed from his face. Sean extended his hand in the dark and felt the face of his rescuer; it was Trace. Suddenly remembering the Green Sword, Sean felt for it at his waist. Thankfully, the sword was firmly in place, and Sean felt relieved for a moment. Where, he wondered, were the others—Serath and Berryl and Brandon? Had Brandon sacrificed himself as the prophecy had foretold, and was he even now lying broken and dead somewhere nearby?

Slowly Sean and Trace moved backwards through the darkness. Sean would make out a translucent curtain in one direction, and guessed it was the waterfall.

The screams of Silarith were vanishing in the distance, but Sean thought he could make out the shouts of orcs not far distant. They were probably probing the pool which lay beneath the falls, looking for his body.