One Hundred Years in the Spotlight (2011)

©2011 by Dallas Denny

Source: Denny, Dallas. (2011, 21 October). One hundred years in the spotlight: Depictions of transgendered people in the media and how everything is changing. Workshop presented at Fantasia Fair No. 37, Provincetown, MA, 21 October, 2011.

This presentation came about because Jamison Green and I are co-authoring a 30,000 word chapter for the upcoming book Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, edited by Dr. Laura Erickson-Schroth.

Our chapter is about the portrayal of transsexual and transgendered people in the media.

One thing I’ve been thinking about is how and why media depictions of us have changed over time. Do they reflect the way we’re seen at the moment? Do they lag behind? Or do they perhaps lead the way?

Here are three observations about the nature of truth from German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. In my own lifetime I’ve seen them played out several times in struggles for social justice.

And so I’ll begin by taking a look at the social and political progress of Black Americans, and of transgendered and transsexual people, as reflected by Schopenhauer’s truisms. Then we’ll look at some representations of us on television and in the movies and see how they’ve changed over time. Finally, we’ll look at just who created these media representations and see how things have changed since we’ve begun to add our own voices.

Schopenhauer’s truisms apply to the struggle for civil and human rights of all groups: women, African-Americans, the disabled, gay men and lesbians, and us. I’m always reluctant to compare the struggles of other groups with that of Black Americans, but Schopenhauer’s truisms can be most clearly seen in the slow march to victory of the Civil Right movement.

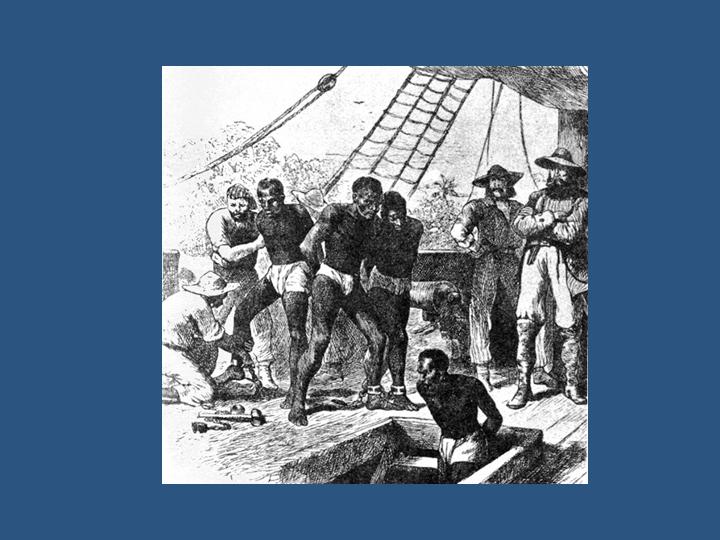

Millions of Africans, a people brought to this country violently against their will, were stripped of all rights and kept as slaves in the American South. They were not socially or legally considered human and could be and often were treated with great viciousness.

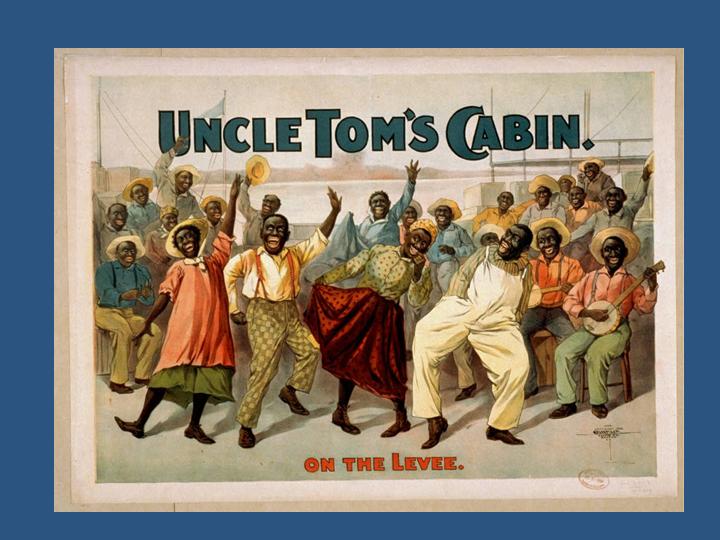

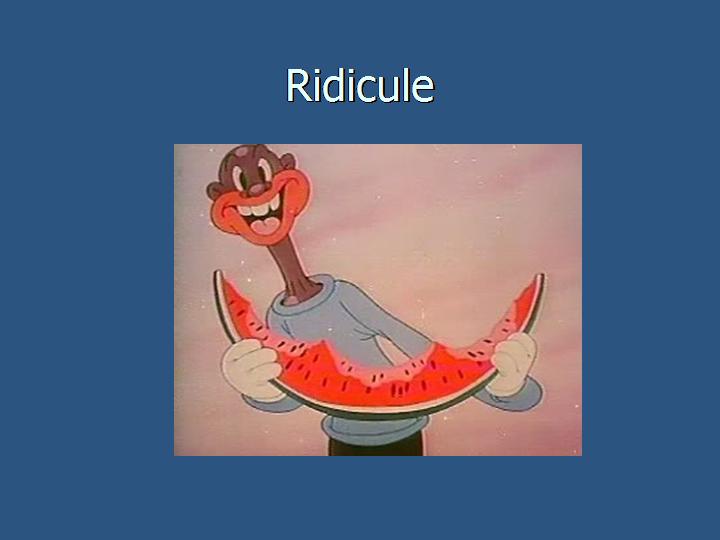

They were ridiculed and caricatured as stereotypes.

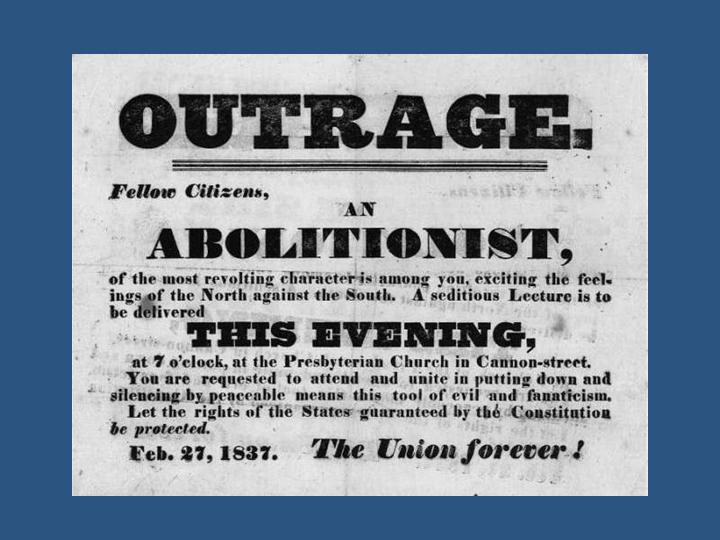

And yet there were forces struggling to help them free themselves. The abolutionist movement started in the early 1800s and grew stronger as the century progressed.

The American Civil War was largely about slavery. Those who say it was about states’ rights conveniently forget or ignore the fact that the state right under consideration was the ability to enslave people.

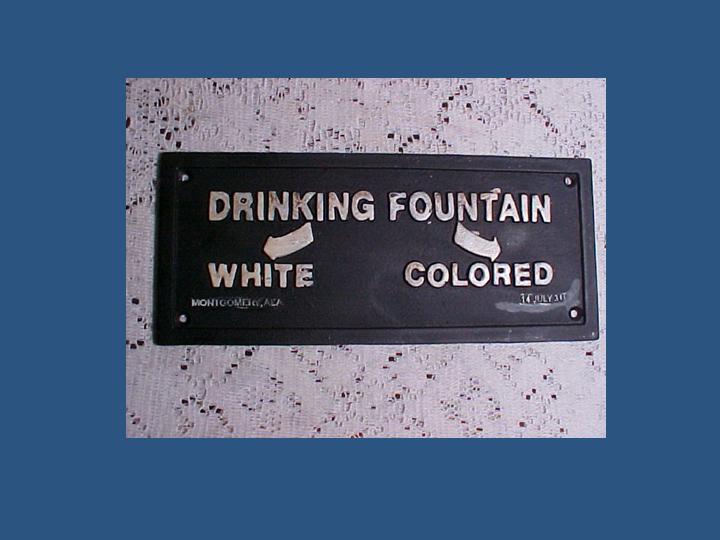

After the Civil War Blacks were free men and women, but the era of Jim Crow– separate but equal (but not really equal) soon settled in. I’m old enough to remember a sign like this at the Sears store in Asheville, North Carolina.

In literature and film, Blacks were largely absent. When they weren’t they were usually portrayed as buffoons, as imbeciles.

This is actor Stepin Fetchit. Note the subservient posture. Note the name.

Jim Crow continued for nearly 100 years– but things began to change with World War II.

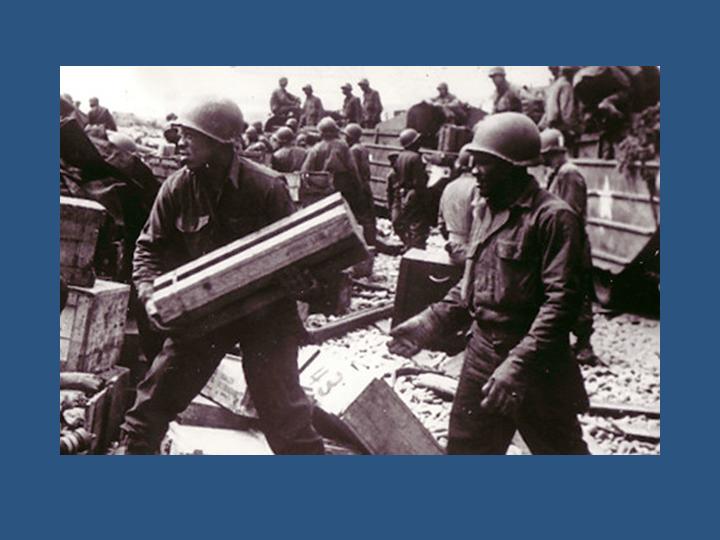

In the war, Blacks served in segregated units. The original intent was them to serve as noncombatants.

This photo was taken on D-Day at Normandy.

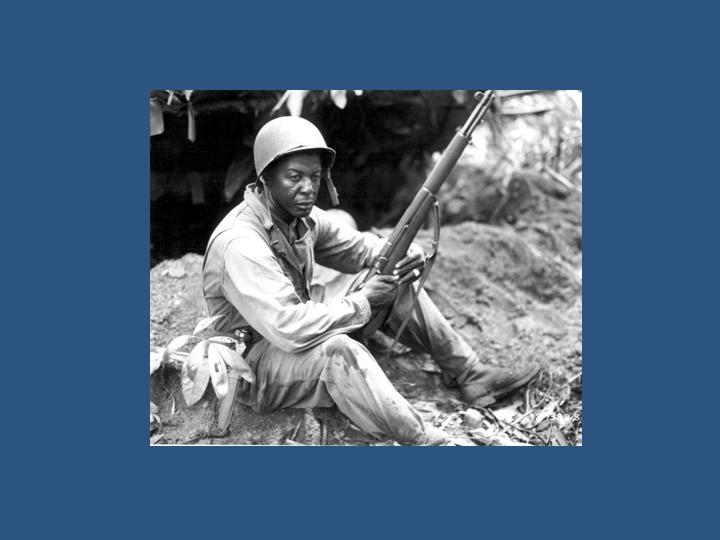

The vagaries of war—unexpected shortages of personnel—resulted in many Black soldiers being sent to combat units. There they surprised officers by defying the stereotypes. Soon generals were asking for more. George S. Patton, who at first believed Blacks didn’t have the mental ability to be good combat soldiers, changed his mind. “I don’t care what color you are as long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sons of bitches.”

When black veterans came back home after the war they faced the same old racism, the same old Jim Crow. Many wondered for just whose freedom they had been fighting. Their dissatisfaction set a mood that would lead to the Civil Rights movement.

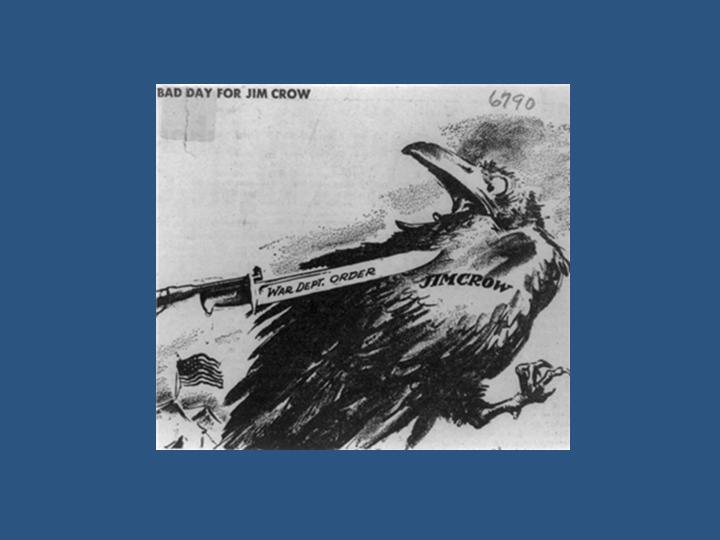

The seeds of change had been sown. In 1948 President Harry Truman ordered an end to racial segregation in the U.S. armed forces. Desegregation began in 1951

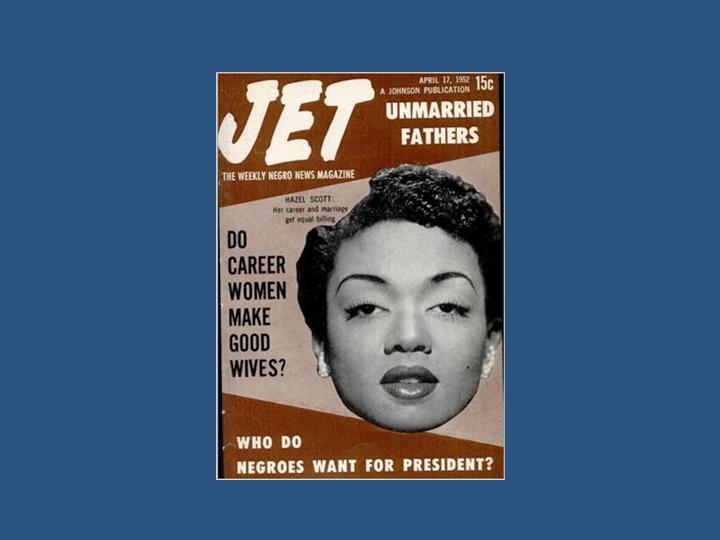

Locked out of mainstream media—there were few roles in films on in print, and few of those could be considered positive—Blacks developed their own media. Here’s Jet, from 1952.

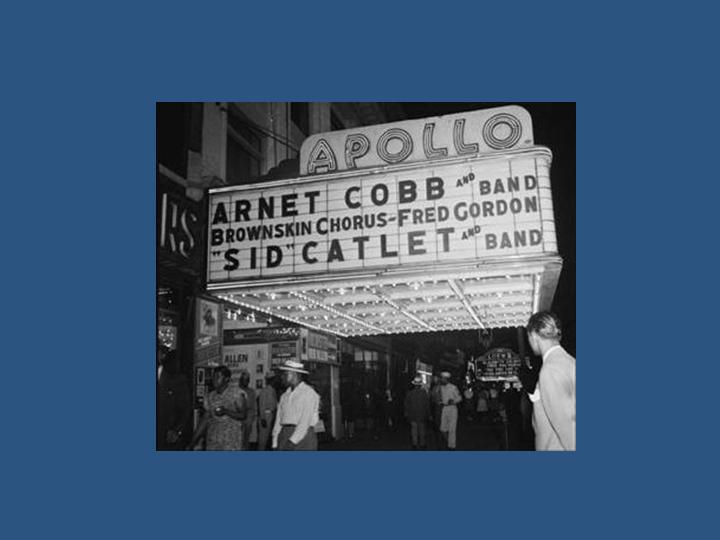

Black Americans made their own culture. Harlem was a center of Black culture and intellectualism.

And they made their own music. Black music was hugely popular with white audiences, which didn’t mind setting aside their prejudices while they listened to R&B.

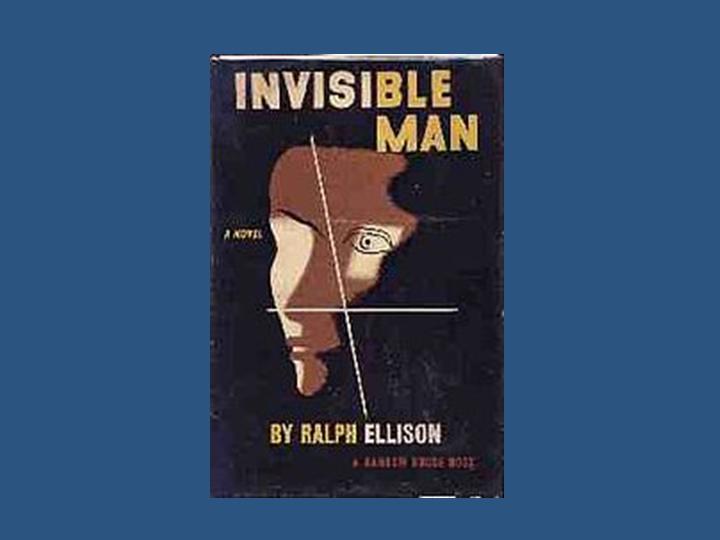

After the war, Black authors began to gain entry into mainstream literature. This is the first edition cover of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, which was published in 1953.

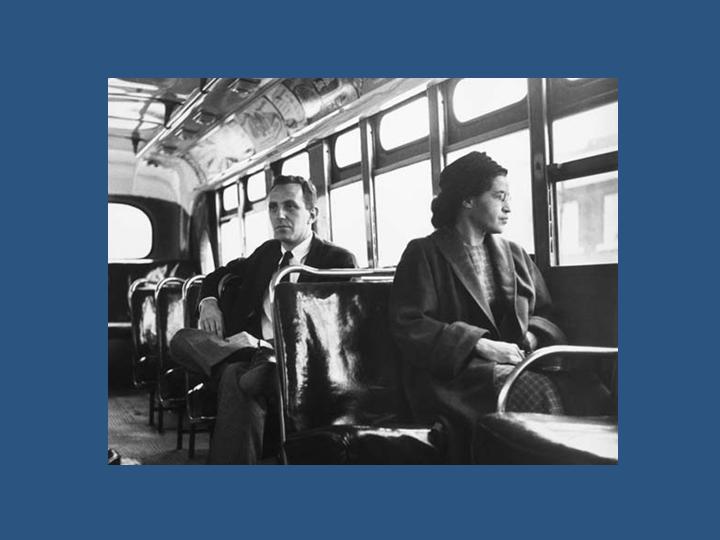

In the late 1950s the Civil Rights movement gained critical mass. Here’s Rosa Parks, who defied a bus driver’s orders to move to the back of a Montgomery, Alabama bus.

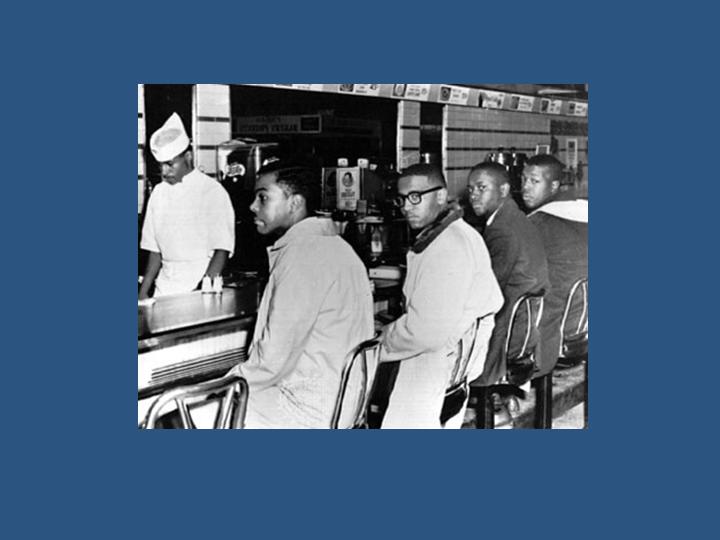

Soon blacks were agitating for equal rights. This is a sit-in at a lunch counter in the South.

This is from the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 1964.

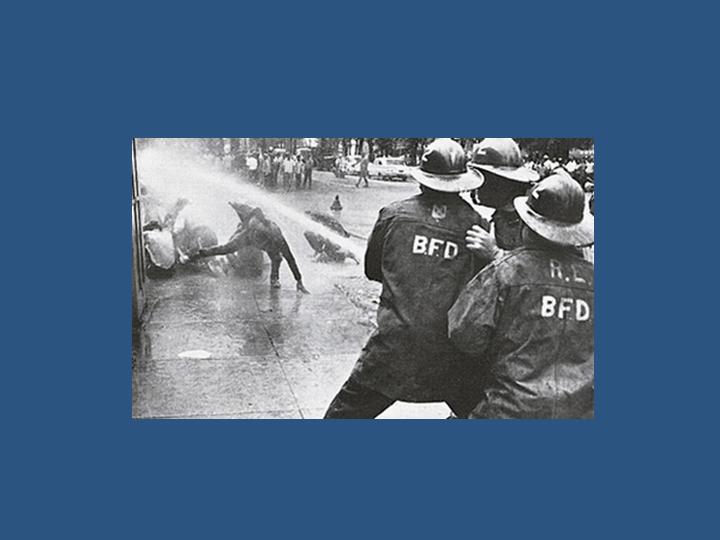

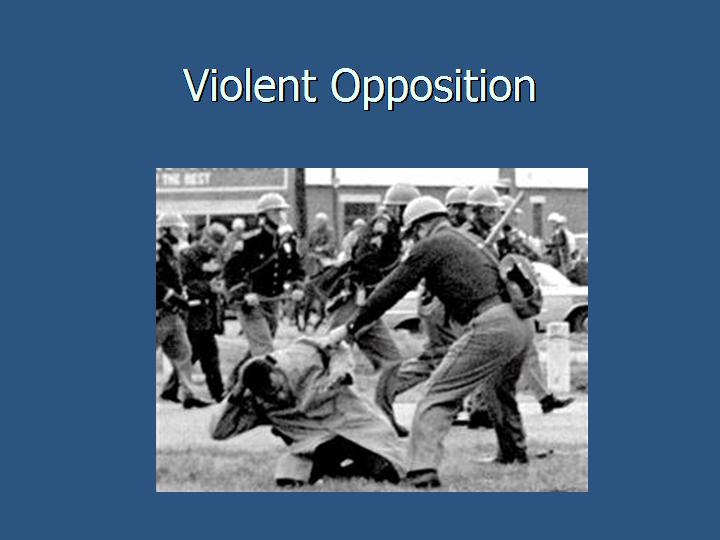

Civil Rights actions were met with violent opposition from White reactionaries.

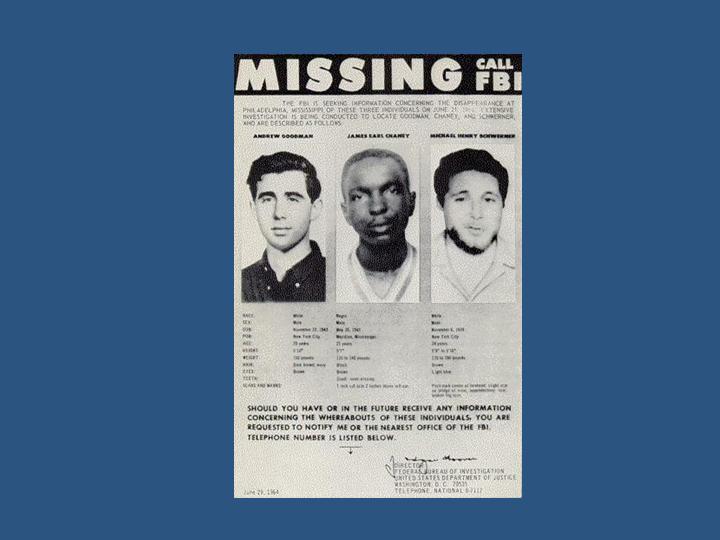

Missing civil rights workers, Misssissippi, 1964. And yet today…

Today a Black man is President of the United States and another Black man is hoping to replace him.

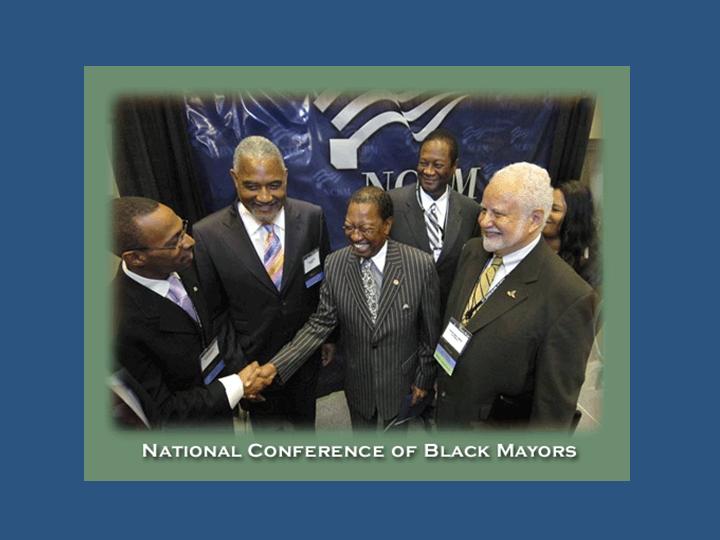

Black men and women and Black culture are integrated into all arenas of American life and culture—although note—everyone in the photo is male.

And does this mean we live in a post-racist America?

It most assuredly does not.

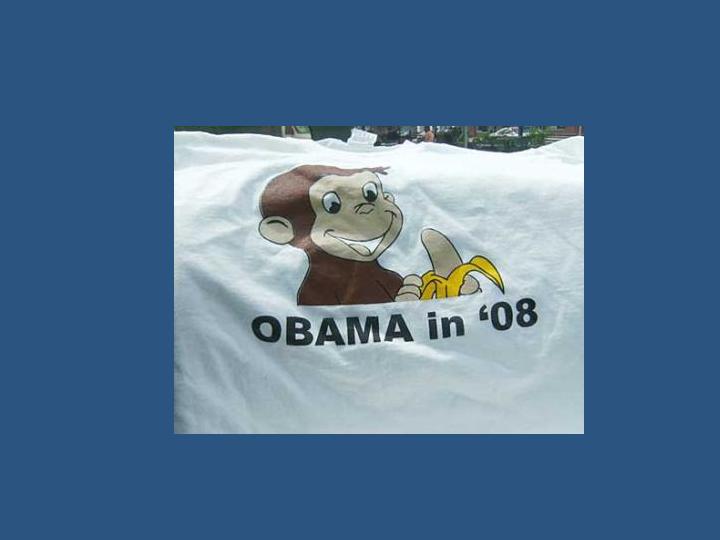

This image showing watermelons on the lawn of the White House comes from an e-mail distributed by Los Alamitos, CA mayor Dan Grose.

The resulting controversy resulted in Grose’s resignation.

To recap…

Black Americans moved from being objects of derision….

…to being violently opposed…

…To acceptance– more or less. I would like to reiterate: racism is far from dead in America. It’s merely more sneaky. But progress has been remarkable.

For Black American’s, progress toward social justice has followed Schopenhauer’s three truisms!

Although our struggle for rights and recognition hasn’t progressed nearly as much as that of Black Americans—it’s much newer—we’re following the same trajectory. This is, from objects of ridicule through persecution to acceptance. Our struggle was late to begin, but progress over the past twenty years has been astonishing.

Not that long ago we were universally mocked and ridiculed– and there were no voices—including our own— to call bigots to task.

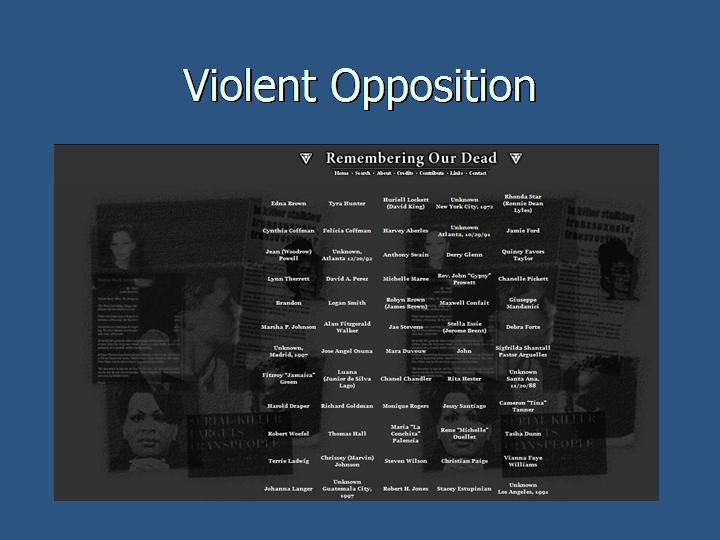

Along with this ridicule came violence. But eventually we began to fight back.This is the web page Remembering Our Dead, which lists every trans victim of Violence editor Gwen Smith learned about.

For more than ten years now annual Transgender Days of Remembrance have been observed around the globe.

Remembering Our Dead was started a project of the nonprofit Gender Education & Advocacy, which was once known as AEGIS, The American Educational Gender Information Service. I founded AEGIS in 1990.

The backlash against us has grown stronger as right-wing political groups and conservative Christians have grown more aware of us. But over the past twenty years we’ve made amazing legal progress and have acquired staunch allies.

Part II

How We Have Been Depicted in Film

We’re just seen how Schopenhauer’s truisms work with Black American and with the trans community and heard how things have changed for we transpeople. Now let’s look at some representations of transsexuals and transgendered people in the media while keeping Schopenhauer’s truisms in mind.

In other words, has our progress on film paralleled our real-world progress?

To keep things simple, I’ve limited myself to film.

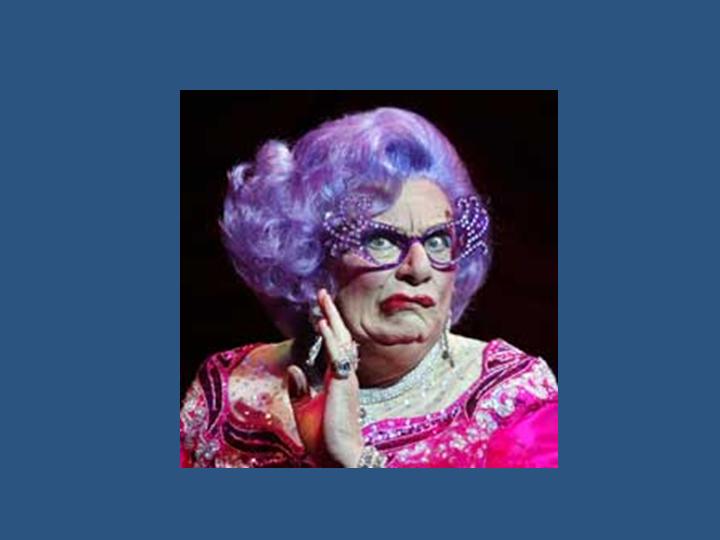

I’ve identified several on-film themes or traditions. The first is the Pantomime Dame, a term that comes from British theater traditions.

This is Australian actor Jack Kearns as a Pantomime Dame. This picture is also from the late IXth or early XXth Century.

Pantomime dames were farcical, playing their roles campily and often looking ridiculous.

The pantomime tradition continues today in characters like Barry Humphries’ Dame Edna Everage.

Here’s Flip Wilson as Geraldine Jones on the 1970s Flip Wilson Show. Geraldine was the TV equivalent of a pantomime dame.

What characterizes the Pantomime Dame is the comedic portrayal of a woman by a man. The audience is in on the joke. The audience knows the woman is being played by a man. But the other characters aren’t in on the secret. However over-the-top the masquerade, the character herself typically isn’t questioned or challenged as a woman.

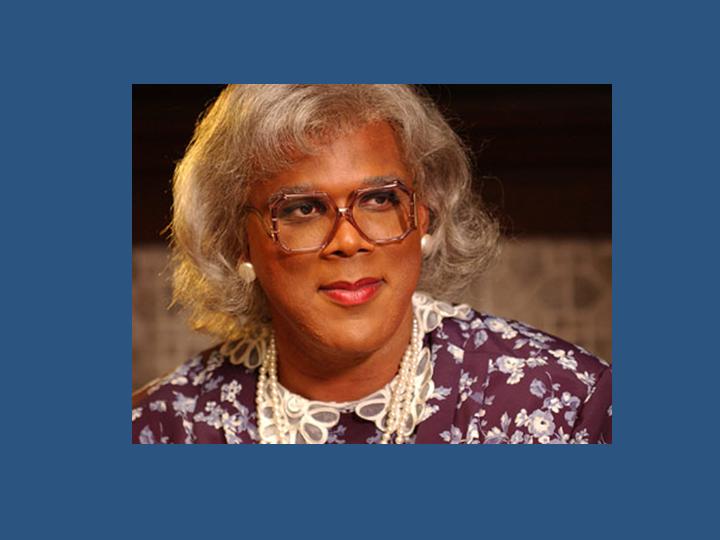

Here’s Tyler Perry as Medea. He carries on the tradition.

Other early on-screen impersonations of the other sex involved masquerade—A man impersonates a woman, or a woman impersonates a man. Early masquerades typically drew heavily on comedic impersonations from vaudeville and pantomime.

Charlie Chaplin got into drag in at least three of his films.

In masquerades, crossdressing was played for laughs. This is Mickey Rooney doing Carmen Miranda in Busby Berkeley’s 1941 Babes on Broadway. Clearly, here the other characters are in on the gag. They know Carmen is actually their male friend.

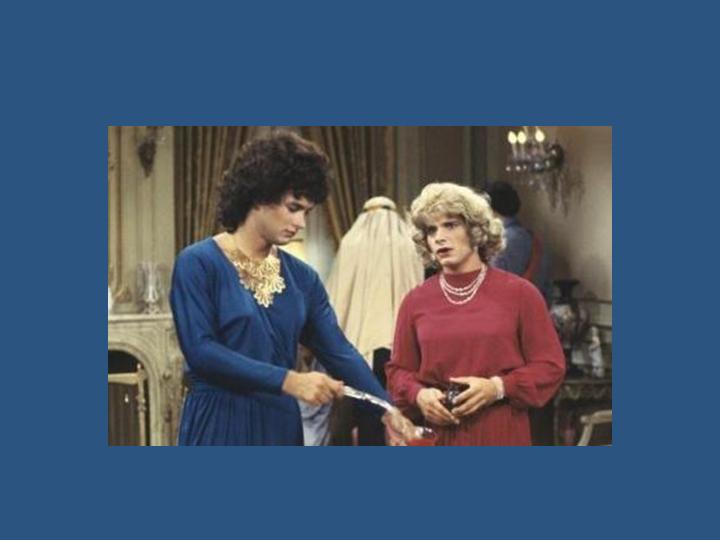

Masquerades required a situation to explain the crossdressing because of course no man or woman in their right mind would impersonate the other sex. The situations were usually contrived and often ridiculous. Here Tom Hanks and Peter Scolari in the 1980s TV show Bosom Buddies dress as women “to be able to afford a place to stay.”

When the impersonation wasn’t entirely farcical, and especially when a character seems to enjoy the crossdressing (as Jack Lemmon’s character does here), tension was relieved only by the most demanding of situations. Here Lemmon and Tony Curtis are trying to pass as women because they witnessed the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and are on the run from the mob. The film is Billy Wilder’s 1959 Some Like It Hot, which won the top spot in the American Film Institute’s top film comedies of all time. Tootsie took the number two slot.

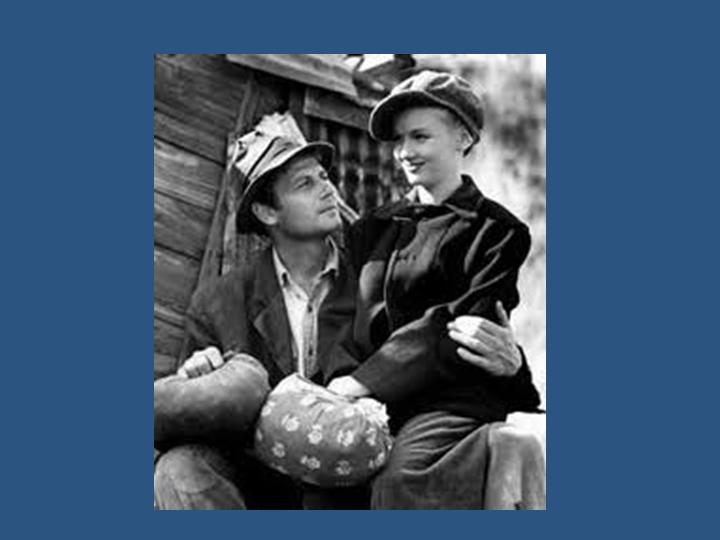

In masquerades there’s a constant tension between the crossdresser(s) and other characters, who either know of the impersonation and are involved as accomplices or don’t know but might find out at any time. Here are Joel McRae and Veronika Lake in Sullivan’s Travels.

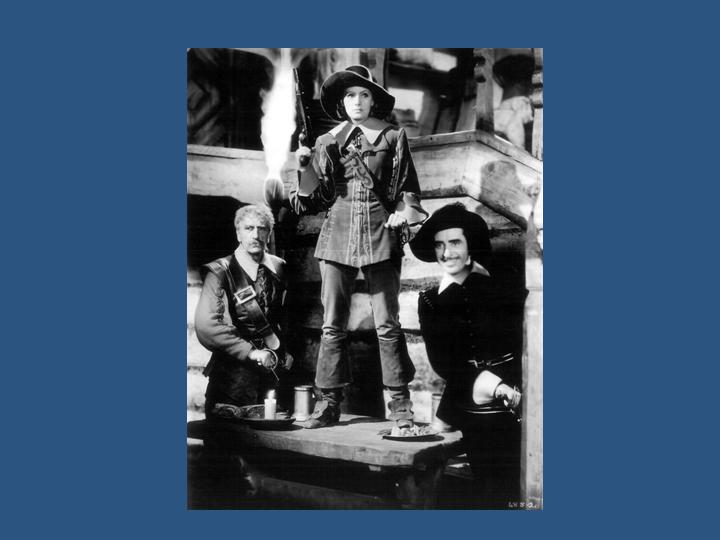

Neither the masquerade nor the pantomime impersonations featured characters with actual issues of gender identity. Films which do so were until recently quite rare. Here Greta Garbo plays the crossdressing Queen Christina of Sweden in the biographical 1933 film Queen Christina.

She was immaculately made-up and coiffed, of course.

When transgendered and transsexual characters did hit the silver screen, they did so as murderers. Alfred Hitchcock set the tone with 1960’s Psycho.

Psycho was based on a short story by writer Robert Bloch, who based his tale on the real life serial killer Ed Gein. Anthony Perkins played a psychotic young motel owner who killed while dressed as his mother.

Psycho was immediately copied—for instance in William Castle’s 1961 Homicidal.

The crossdressed serial killer quickly became a meme. Here’s Rod Steiger in No Way to Treat a Lady.

Brian de Palma’s 1980 film Dressed to Kill. The theme was still manifesting as late as 1991 in Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs.

For several decade every time I saw a transgendered character on television or in a movie, I could be pretty sure he or she was the killer.

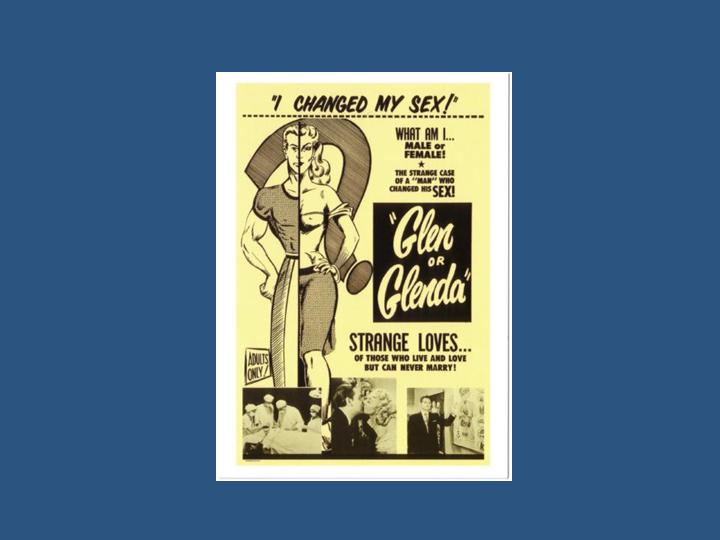

…And then there was another tradition— one in which the filmmaker attempted to authentically portray trans characters on the silver screen. 1953’s Glen or Glenda was a stumbling attempt by crossdressing director Ed Wood to shed a positive light on transsexualism.

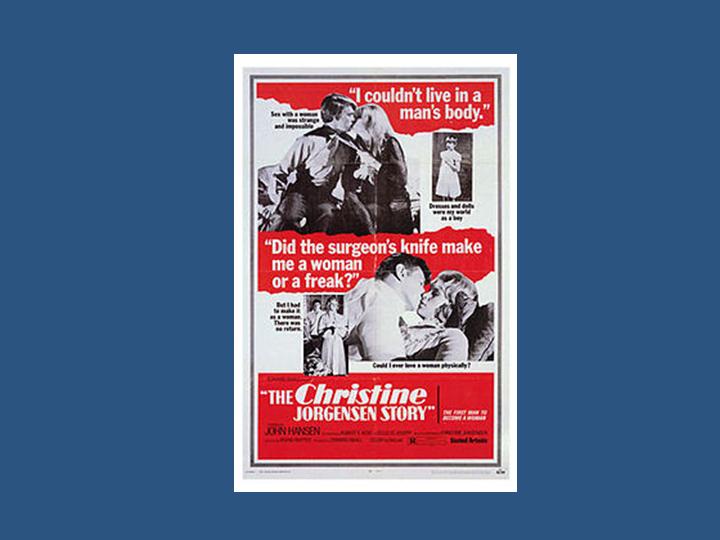

The Christine Jorgensen Story, which appeared in 1970, painted a sympathetic portrait. Renée Richards’s biography, Second Serve, appeared on television in 1986. Interestingly, Jorgensen was played by John Hansen. Richards, who was far less feminine than Jorgensen, was played—convincingly, as it turned out—by Vanessa Redgrave.

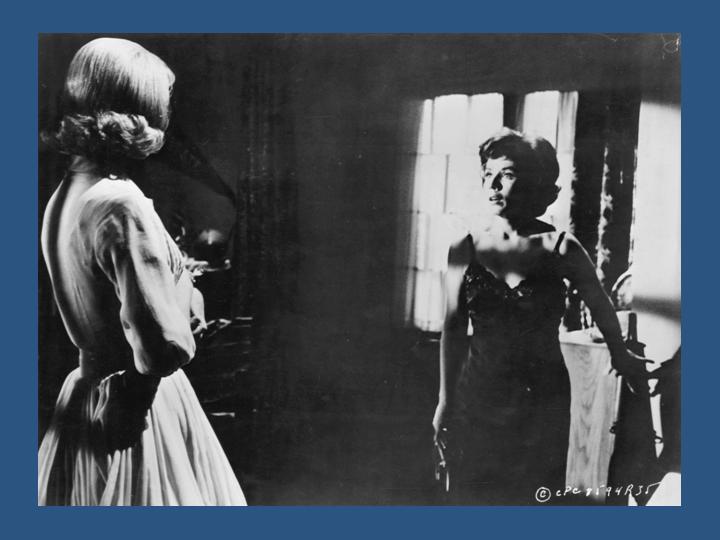

To my eyes, the 1972 film I Want What I Want is the most accurate representation of transsexualism ever filmed. Starring Anne Heywood and directed by John Dexter, it was based on Geoff Brown’s 1966 novel with the same name.

All of these were attempts to look at transsexualism in a serious manner. In 1975 the TV series Medical Center featured a two-part arc called The Fourth Sex, in which Robert Reed—yes, the father in The Brady Bunch—played a transsexual physician named Pat Cadisson. Cadisson didn’t crossdress until after the surgery. I remember the last scene showing a dejected and rather frumpy-looking woman sitting in a chair and staring out the window of her hospital room. It wasn’t a realistic depiction, but it was nonetheless an attempt to look at the subject seriously and sympathetically.

And then there are documentaries. Lee Grant directed What Sex Am I?, an early documentary about transgendered and transsexual people.

It appeared in 1984.This is Cathy, a transsexual woman from Houston.

In recent years, of course, there have been dozens and maybe hundreds of documentaries about us.

So—with the exception of the transvestite slasher killer spinoffs, the early portrayals of transgendered and transsexual people were respectful.

(I’m not including pantomime and masquerade traditions here in making this statement, as they were about gender transgression and not about transpeople at all.

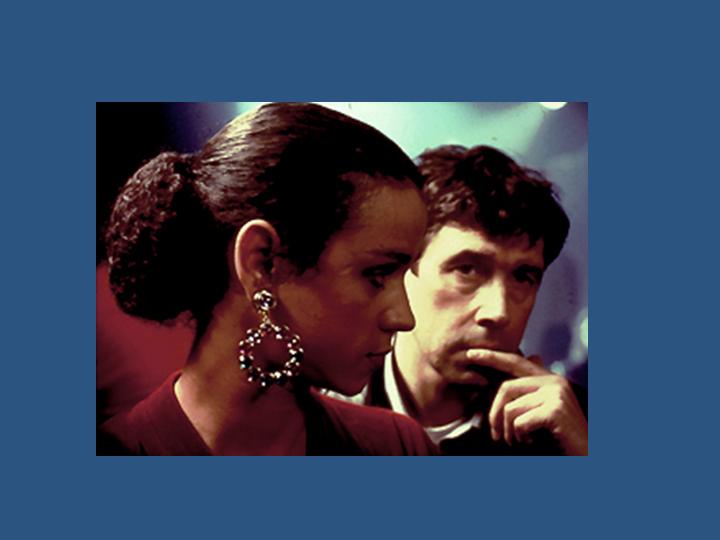

The last twenty years have seen an explosion of extraordinary films with positive portrays of transsexual and transgendered characters. Here are Jaye Davidson and Stephen Rea in Neil Jordan’s 1992 The Crying Game. I can think of at least twenty others.

Clint Eastwood’s 1997 adaptation of John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil featured a real-life transgendered person—The Lady Chablis, at right. Most filmmakers used cisgendered actors to play the trans characters. This continues even today.

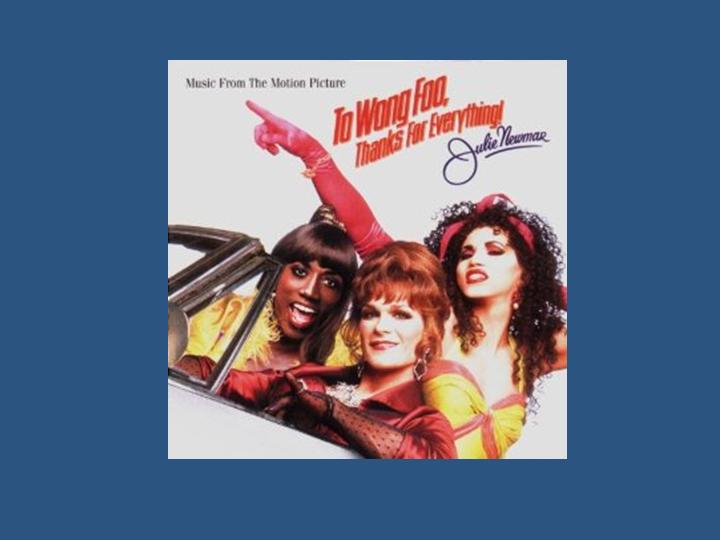

Most films, however positive their portrays of transendered and transsexual characters were directed by cisgendered men and women. I suspect but couldn’t confirm that Beeban Kidron is a lesbian. She directed 1995’s Too Wong Foo. I know no gay man would have named the drag queen of the year award The Drag Queen of the Year Award!

John Leguizamo’s portrayal of drag queen Chi-Chi Rodriguez was to my mind the best part of the film.

Stephan Elliott’s 1994 Priscilla, Queen of the Desert brought a drag sensibility lacking To Wong Foo. The costumes were fabulous.

Elliott understood drag, I’m certain, but I don’t think he understand much about transsexualism. Or maybe Terrance Stamp was just a poor choice to play Bernadette, the film’s sole transsexual. Even so, the director and the actor did their best to paint a three-dimensional picture of Bernadette.

Some of these films covered important issues like violence against transgendered people. Here’s a scene from Kimberly Peirce’s 1999 film Boys Don’t Cry, which was based on the life of Brandon Teena. But Boys Don’t Cry, like the other films I’ve shown here (except Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda, were all made by cisgendered people.

Transgendered and transsexual directors haven’t yet landed any big-budget productions– although Larry Wachowski of The Matrix is now by all accounts Lana, so who knows what will soon transpire on the big screen?

Trans directors do exist and screen works at film festivals. For example, Canadian trans activist and sex worker Mirha Soleil-Ross has been making short films since the early 1990s. My favorite is Adventures in Tucking.

Here’s the IMDb page for Joelle Ruby Ryan’s 2003 Trans Amazon.

So– in this brief look at films have we seen Schopenhauer’s truisms reflected?

Not exactly. While pantomime performances and situational crossdressing comedies certainly treated crossdressing as a joke, it was the crossdressing itself, and not those who crossdressed, which were considered ridiculous. We ourselves were’nt yet consequential enough to warrant notice; we were entirely ignored.

With the exception of the transvestite killer stereotype, however, the earliest film and television treatments of transgendered and transsexual people tried to be positive.

This is a scene from 1952’s The Member of the Wedding, adapted from Carson McCullers’ novel of the same name. Frankie, the prime character, certainly shows signs of being transgendered. And according to a biography, McCullers was herself FTM.

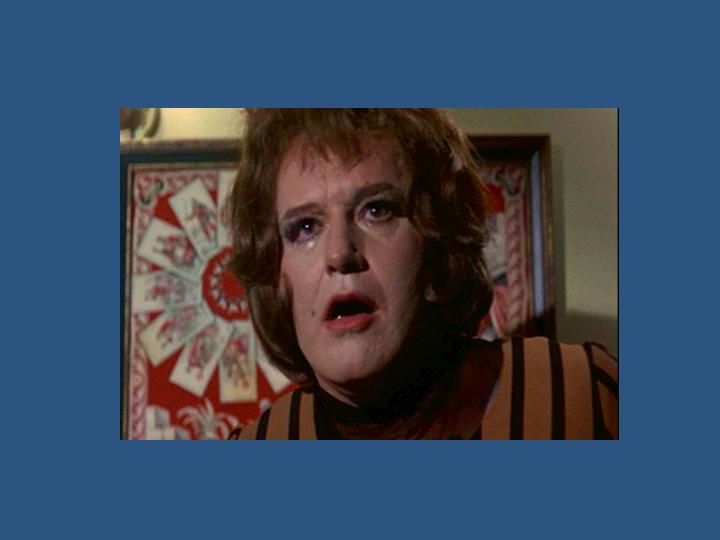

Transphobia manifested on the screen primary in the trans-as-psycho-crazed-serial-killer motif. Here’s Ted Levine as Jamie Gumb from 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs, hopefully the last of this unfortunate ouevre.

Recent portrays– including a large number of documentaries– continue to show us in a positive light– so acceptance? Yes. I would say that apart from Psycho and its knockoffs, television and movies have been ahead of the Schopenhauer curve.

These images are from The Sundance Channel’s 2005 documentary mini-series TransGeneration. Documentaries are a new tradition in screen and on television. Another new tradition—limited, thankfully to television—is the reality show. Trans contestants appear regularly on some of the most popular shows, and one—Ru Paul’s Drag Race— is entirely about female impersonation.

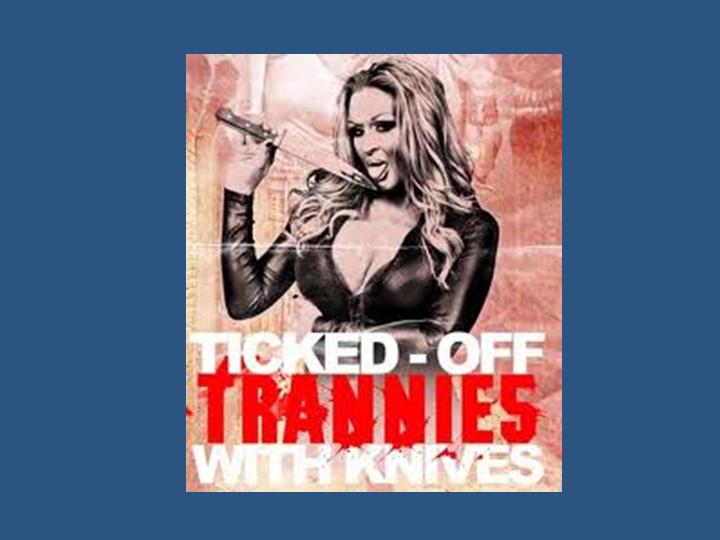

That’s not to say there aren’t still stereotyped portrayals of us. This is the poster from Israel Luna’s 2010 Ticked-Off Trannies with Knives. Many transpeople took offense.

What we’ve seen so far are portrayals of us by nontranssexual and nontransgendered directors. That’s because until recently, transgendered and transsexual voices have been absent from the discourse. This applies not only to movies and television, but to literature, books about gender, and scientific papers. The only media area that was open to us was autobiographies– and that was limited to transsexuals.

That all began to change in the 90s. Early in this century, out transgendered and transsexual people broke into the academy, finding positions at colleges and universities. Trans writers began to contribute to the scientific literature and to publish books and plays. We’ve already noted that films by transsexual and transgendered directors have begun to appear.

As Audre Lorde noted, the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.

Now we are coming to the table with our own tools.