T-Bird: Jerzy Kosinski’s Peculiar Literary Fascination with Transsexual Women (1994)

©1994, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (1994, Winter). T-Bird: Jerzy Kosinski’s peculiar literary fascination with transsexual women. Transsexual News Telegraph, pp. 16-18. Reprinted in TG Forum, May 1999.

T-Bird: Jerzy Kosinski’s Peculiar Literary Fascination with Transsexual Women

By Dallas Denny

Jerzy Kosinski led an interesting and in many ways difficult life. He spent his early years as an abandoned child in Eastern Europe during World War II, and ended his life by his own hand in 1991 after being diagnosed with a fatal illness. Somewhere in between, he immigrated to the United States and became a best-selling author.

Kosinski was the friend of Polish immigrant Wojiciech “Voytek” Frykowski, and through him met director Roman Polanski, who was the husband of the ill-fated Sharon Tate. Kosinski was a sometime visitor to 10050 Cielo Drive, the scene of the infamous Manson Family murders. Kosinski was scheduled to have been there on that fateful night when Voytek, Tate, hairdresser Jay Sebring, Stephen Earl Parent, and coffee heiress Abigail Folger (Voytek and Folger were introduced to each other by Kosinski), were shot, stabbed, and bludgeoned to death by the followers of Charles Manson.

Because it was made into a very funny movie starring Peter Sellers, Kosinski is perhaps best known as the author of Being There, the story of Chance the Gardener, who was an absolute dunce, but who said things other people thought were extremely wise—you know—sort of like Ronald Reagan. But Kosinski wrote other novels, most of them far darker, reflecting his troubled life. The Painted Bird, for example, tells of the awful experiences of a young boy orphaned in central Europe during World War II, as he wanders about being exploited and abused in every imaginable way by people whose primary reason for misusing him seems to be that they can get away with it. Cockpit is the story of a man with a malevolent streak—to put it mildly— which causes him at various times to spy on people making love, set up innocent victims for persecution and torture by the secret police in his Eastern bloc home nation, and fatally irradiate a woman who had been so thoughtless as to annoy him. Blind Date is about a man who seems to be equally comfortable with blowing up a cable car full of people and brutally teasing a young girl by insisting that she is really a boy. Passion Play tells of a man who wanders about in a motor home, keeping peripheral to the horsey set and habitually using false identification, like a Dick Francis character gone awry.

Kosinski’s works are not novels in the same way that Thomas Wolfe’s works are not really novels and Robert Altmann’s films are not really movies, but rather loosely joined vignettes which are more character study than plot. Perhaps it is this unusual approach which caused Kosinski to reap a variety of literary awards for his work, beginning with Steps, a collection of short stories which first appeared in 1957, and for which he won the National Book Award in fiction. Because of the way his works are structured, it is sometimes difficult to say what they are “about.” But there are a number of themes which keep reoccurring, and one of them is male-to-female transsexualism.

For Kosinski’s protagonists, transsexual women are sexual creatures, objects of simultaneous desire and disgust. His transsexual characters are one-sided, of no conceivable use other than sexual objects. When they are beautiful, they are feminine and seductive. When they lose their looks, they are repulsive and repellent. The reader does not get a multidimensional picture of the character, as in John Irving’s treatment of ex-football pro Roberta Muldoon. What character development there is serves only to emphasize the character’s underlying sexuality.

It is in Steps that we see the beginnings of this preoccupation with transsexual women as objects of desire, as Kosinski’s unnamed protagonist naively picks up a heavily made-up woman for sexual purposes; she turns out not to be a woman at all, but a rather clumsily disguised man. One gathers that “she” could easily have been a member of the pre-sex-test East German Olympic Team. The protagonist is appalled, but the sexual liaison is nonetheless completed.

By the time of 1977’s Blind Date, the protagonist is considerably more sophisticated, and so is Kosinski’s treatment of transsexualism. His transsexual characters have certainly become more passable. George Levanter rescues “Foxy Lady,” (he names her after her t-shirt), a beautiful Middle Eastern woman who is stranded in the no-man’s land between Switzerland and France. They quickly develop a sexual relationship, but she will not have intercourse, claiming that she recently had an operation for removal of a uterine tumor. When her bandages come off and they finally do the deed, Levanter is disturbed by the fact that she is fantastically skilled at pleasing him—more so than any other woman.

He felt possessive of her beauty; still her sexuality was ambiguous to him. He could not pin down exactly what she wanted from their lovemaking, yet she seemed to understand everything he wanted. Whereas other women had at times responded as if his urgings were odd, she accepted his needs as if they were to be expected…. In a sensual vigil over his flesh, she monitored every detail of his release, anxious to know the duration and intensity of each spasm. ( p. 131)

Finally, a “friend” of Foxy Lady tells Levanter the exact nature of her “tumor.”

After explaining to Levanter the reasons for her change, Foxy Lady takes Levanter to a New York night club, where she shows him an upstairs room where all the old queens go, as if, having lost their sexual attractiveness, they were good for nothing more.

Under the thick make-up, their skin was coarse and wrinkled, their dyed hair was thin and scanty with balding patches, which some tried to cover with wigs…. Their artificially overblown breasts had become soft, and flapped like pancakes on their barrel chests. Their hands, covered with brown spots, were unnaturally broad, nearly square; their fingers, the nails bright with polish, seemed uniformly thick. (p. 138)

“Their only salvation is that the club owner remembers them as foxy ladies, young and fresh and lovely, and gives them dinner every night without charge,” Foxy Lady tells Levanter, adding that she expects to eventually end up upstairs, too (p. 138).

In 1979’s Passion Play, the protagonist, Fabian, sets up Stephen Gordon-Smith, an unsuspecting acquaintance, with Diana, a beautiful (of course) postoperative woman. Gordon-Smith falls in love with her. Fabian then tells him, “She’s a transsexual, a man.” (p. 113). Fabian simultaneously assures Gordon-Smith that Diana is a source of great potential embarrassment, but that he (Gordon-Smith) is not homosexual for having enjoyed himself with her. To Fabian, Diana, while desirable as a sex toy, is not suitable for the long-term relationship that Gordon-Smith has in mind because she is, in the final analysis, a man. Having sex with her is not a homosexual act, but marrying her would somehow be.

Fabian himself is sexually active with transsexual women. He regularly brings Manuela, a voluptuous and beautiful Mexican-American non-operative woman (she is afraid that sex reassignment surgery will destroy her sex drive), to his motor home, where they mutually seduce other women. Fabian then watches the two women make love to each other, eventually joining in.

Kosinski’s male characters see transsexual women, no matter how beautiful and passable on the surface, as altered men. Whether it is Foxy Lady’s uncanny ability to know what pleases Levanter, or the male sexuality which underlies Manuela’s zaftig exterior, there is a sense of underlying masculinity in his transsexual characters, at least as seen by his protagonists. This perception of transsexual-women-as-men is a well-known attraction for some men—it is a fascination which drives the pornography industry, causing the production of countless “she-male” books and videos.

He hovered over her, in awe of a body that had no fault, that seemed to incarnate the secret of who he was: at her mouth and breast, he was a boy necking with a girl; entwined with her, entering her, he was a man taking his woman; arousing her with his hand, he was a boy at play with a man; straddling her as she lay helpless beneath him, he was a man toying with a boy; pinioned by her, he was a man at the mercy of a boy. (Passion Play, p. 119)

Kosinski’s works have an autobiographical ring to them: he was an abandoned child in World-War II Europe; he wrote a novel about an abandoned child in World-War II Europe. He immigrated to the U.S. from Eastern Europe; he wrote novels about immigrants from Eastern Europe. In Blind Date, Levanter fantasizes about the Manson killings; Kosinski doesn’t even bother not to use the actual first names of the victims. So what is signified by his regular use of transsexual characters? Did Kosinski have transsexual inclinations himself, or was he what is known as a “T-bird” or “Trans Fan”?

What Jerzy Kosinski’s actual experiences, if any, with transsexual women were, we can of course never know, but his vision of them as objects for sexual pleasure, and nothing more, does leads one to wonder what was going on behind the scenes.

Perhaps it is this preoccupation with transsexual women as sexual objects which caused Kosinski’s publisher, Vicki Marshall of Scientia-Factum, Inc., to refuse my request to reprint excerpts from his novels in my magazine, Chrysalis, on the grounds that my selections were “not typical” of his works. The excerpts I asked to publish were the sections concerning transsexualism. They were not typical in the sense that the football game or the “Pros from Dover” scenes are not typical of Robert Altmann’s M*A*S*H, or Eugene Gant’s hanging out at the drugstore in downtown Altamont is not typical of Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel. All of M*A*S*H is not about football and trips to Japan, nor is all of LHA, as those in the Thomas Wolfe Society refer to it, about drugstores, but those scenes are part and parcel of the fabric of Altmann’s and Wolfe’s works, just as Kosinski’s recurring treatment of transsexualism is integral to the tapestry of his work. The sexual escapades of Kosinski’s characters with transsexual people are not exactly Mom and apple pie, I will submit, but neither is blowing up a cable car full of people. What’s the difference?

I regret that the publisher has continued to refuse the right to reprint, as any literary treatment of transsexualism is rare, and Kosinski’s writing, although disturbing and sexual in nature, is of high quality and worthy of sharing. And who knows—reprints might even have helped sell a few of his books. I would have quoted Kosinski’s works more extensively in this review, but I am wary of lawsuits. I suggest you check out Blind Date and Passion Play; the sentences I used are part of lengthy passages about transsexual women.

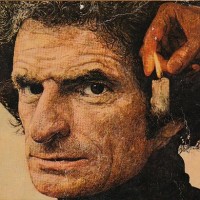

I will close with a vignette of my own. Kosinski’s hawk-faced profile appears on the back of his books; it is distinctive, a visage lean and hungry, like yon Cassius’. Some years ago, I happened to be in Lipstix, a drag bar in Atlanta, now long closed. I found myself sitting next to a cross-dressed man. He had a middle-European accent and the slight build my mind’s eye had envisioned for Kosinski. And he had the same gaunt face—the sharp nose, the dark, piercing eyes, the heavy brows, the forehead lines, the square chin that no amount of makeup could hide. He was cruising the transsexual women in the bar. “So you know all of the pretty girls,” he said to me wistfully, as he looked lustily after an obviously transsexual blonde who had greeted me.

I seriously doubt that I was sitting next to the crossdressed Jerzy Kosinski. Perhaps he never crossdressed in his life. Still, Atlanta is a popular place to be, not unreasonable for a popular writer who repeatedly writes of beautiful transsexual women. And it occurred to me, perhaps because I was drinking Perrier instead of liquor and my mind was reasonably alert, that if Kosinski was himself one of the girls, a sure enough “Painted Bird,” that would explain the recurrence of transsexualism in his novels.

I’m sure Kosinski wasn’t transgendered, mind you. It’s a great mistake to hazard guesses about an author based on his works, and in particular, to automatically assume that fiction is autobiographical. It’s just that I have a suspicious nature, and so much of Kosinski’s work is based on his personal experience. His characters are so blatantly sociopathic that they scare me and lead my mind in dangerous directions. I’ve always wondered, for instance, why Kosinski picked that particular night to miss the party at Sharon Tate’s house. Was Kosinski more like his Machiavellian characters than his publisher cares to admit? Was he listening to an inner voice that told him to stay away, or did he perhaps play an unchronicled role in what happened that fateful night at 10050 Cielo Drive?