Where is Our History? (Censored Editorial, 2004)

©2004, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (2004). Where is our history? Censored editorial for Transgender Tapestry Journal. In 2007 I formatted the editorial as a press release, but I don’t think I actually released it.

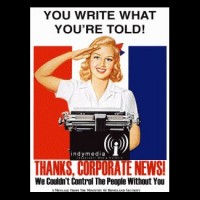

It was frustrating beyond belief to have this important editorial stonewalled for so many years. It never did appear in Tapestry.

About

I wrote this editorial in 2004 for inclusion in Transgender Tapestry magazine, of which I was at the time editor-in-chief. I present it as originally written.

At the request of Denise Leclair, the Executive director of Tapestry’s parent organization, the International Foundation for Gender Education, and against my better judgment, I deferred the editorial to the next issue. And the next issue. And the next issue. And the next.

I finally put my foot down and insisted “Where Is Our History?” would run in Tapestry #110. When it became clear that because of Ms. Leclair’s intervention and despite my appeal to IFGE’s Board of Directors, it would not appear in #110, I resigned my editorship in August, 2006. Issue #110 subsequently appeared without the editorial.

I resigned over general issues of journalistic integrity, and specifically because IFGE was suppressing vital information the larger community needed to know. I finally released the editorial to the community in 2007.

I’m happy to say Ms. Swin’s collection has finally officially surfaced. In September, 2011 at the WPATH symposium in Atlanta, Dr. Aaron Devor, sociologist and dean at the University of Victoria in British Columbia gave a presentation about the collection and said the official opening of the archive is set for early 2012.

Where is Our History Text

©2004, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (2004). Where is our history? Censored editorial for Transgender Tapestry Journal. In 2007 I formatted the editorial as a press release, but I don’t think I actually released it.

Censored Editorial for Transgender Tapestry Journal

Where Is Our History?

By Dallas Denny

Until 1990 or so, the transgender community had little sense of its history—I suppose because we were so very busy defining ourselves. Outside of the hands of private collectors and the occasional gender-bending article or item in gay and lesbian archives, there was nothing. Even collectors had little idea of the value of something like a 1955 program book from Mme. Arthur’s cabaret in Paris, or a 1915 postcard of the famous female impersonator Julian Eltinge, or a program from the First International Symposium on Gender Identity or an issue of Virginia Prince’s early magazine Transvestia.

I remember, in fact, way back in 1993 discussing this with Ms. Bob Davis (then plain old Bob Davis) over the telephone. We decided that if we were patient, a market would develop and would determine values. Today, thanks largely to eBay and the emergence of booksellers who specialize in transgender materials, Ms. Bob and I have notions of what transgender historical materials are worth. One might expect to pay more than $400 for the Mme. Arthur’s program, for example, or $425 for an early copy of Transvestia, or $65 for an Eltinge postcard, or $50 for the rare, but rarely collected, symposium program.

The new century has brought increased interest in transgender historical materials. Year 2000 started out with a bang, as the new nonprofit Gender Education & Advocacy (formerly the American Educational Gender Information Service) sought proposals from other nonprofit agencies to receive its National Transgender Library & Archive (see Tapestry #109 for an article about the disposition of this collection; it went, after a rigorous decision-making process, to the University of Michigan). Also in 2000, Rikki Swin, under the auspices of the nonprofit Rikki Swin Foundation, purchased the private collections of early transgender activists Virginia Prince and Betty Ann Lind and the archives of the International Foundation for Gender Education. Swin subsequently purchased a personal collection from Ariadne Kane, one of the founders of Fantasia Fair and another early transgender activist.

At the 2001 IFGE conference in Chicago, attendees were whisked in chartered buses from their hotel to a building in the center city, where they trudged up three steep flights of steps to view the purported future home of Swin’s collection, (A Rikki Swin Foundation press release claimed the building had been purchased by Swin for some three million dollars). The rooms were empty, but guests were assured the collections were stored elsewhere in the building.

At least one person I know (Ken Dollarhide, if you must know) say they actually saw the shelved collections. Swin took out full-page ads on the outside cover of this magazine, prominently featuring her expensive building, paid for the expenses of medical professionals at various transgender conferences, and then—nothing.

By nothing, I mean nothing. No one seemed to know what had happened to Swin or her institute. The building had reportedly been emptied, the collections vanished. The RSI phone number has long been out of service.

Considerably later, Swin reportedly resurfaced in Victoria, British Columbia—for the geographically challenged, Canada’s westernmost province. I managed to suss this out by working my network of acquaintances. It’s probably true (I trust my network), but for the past five years, there has been no official word from Ms. Swin about her foundation or about the collections she has acquired. No word about our history, in other words. It’s missing.

Certainly, Swin isn’t in possession of all of our history—there are other collections, after all—but she does possess a significant part of it— most importantly, personal papers of Virginia Prince, Betty Ann Lind, and Ariadne Kane which document the history of early transgender organizations and of which there are no other copies. She has been absolutely irresponsible and has violated trust by not keeping the community informed of the collection’s condition and whereabouts. It could, for all we know, be poorly stored, shredded, or lost.

Ms. Swin, where is our history?

See also my article “Nice Box. Wonder What’s In It?”