The Problem (1991)

©1991, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (1991). The problem (Novel). (1991). Chapter 1 appeared in Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(1), pp. 17-18, 20. Chapters 1-3 appeared in International TranScript, (1991), #7. Chapter 1 appeared in Amethyst: A Journal for Lesbians and Gay Men, Summer/Fall 1998, pp. 8-9. The first (at least) eighteen chapters were subsequently serialized in Ladylike magazine. The pages reproduced here are:

Dallas Denny. (1995). The problem: Chapters 1-3, International TransScript, No. 5, pp. 30-36.

Dallas Denny. (1993). The problem: Chapter 1. LadyLike, No. 19, pp. 39-31.

Dallas Denny. (1994). The Problem. Chapter 2. LadyLike, No. 20, pp. 39-40, 42.

Dallas Denny. (1994). The problem: Chapter 3. LadyLike, No. 21, pp. 35, 38-39, 41.

Dallas Denny. (1994). The problem: Chapters 4-5. LadyLike, No. 22, pp. 34, 38-39.

Dallas Denny. (1995). The problem: Chapter 6. LadyLike, No. 23, pp. 36-38.

Dallas Denny. (1995). The problem: Chapters 7-9. LadyLike, No. 24, pp. 36-38.

Dallas Denny. (1995). The problem: Chapters 10-12. LadyLike, No. 25, pp. 38-41

Dallas Denny. (1995). The problem: Chapters 13-15. LadyLike, No. 26, pp. 38-41.

Dallas Denny. (1996). The problem: Chapters 16-18. LadyLike, No. 27, pp. 38-41.

The novel has been serialized in part, but never published in its entirety. I’m open to offers.

Here are the first three chapters. Click the tabs to open.

Chapter 3, Chrysalis Pages (PDF)

Chapters 1-3, International TranScript No. 5 (PDF)

Chapter 1, LadyLike No. 19 (PDF)

Chapter 2, LadyLike No. 20 (PDF)

Chapter 3, LadyLike No. 21 (PDF)

Chapters 4-5, LadyLike No. 22 (PDF)

Chapter 6, LadyLike No. 23 (PDF)

Chapters 7-9, LadyLike No. 24 (PDF)

Chapters 10-12, LadyLike No. 25 (PDF)

Chapters 13-15, Ladylike No. 26 (PDF)

Chapters 16-18, LadyLike No. 27 (PDF)

About

Laura Ann Sykes jumped unbidden into my brain in late 1990 or early 1991. In some ways she reminds me of myself; in other ways I wish I were more like her. I suspect to some extent she’s the me-that-might-have-been. No, she’s the me-that-would-have-been if I had had her courage. Her girlhood, difficult as it is, would have been preferable to my boyhood.

I did have a sort of girlhood—a twilight girlhood, an episodic girlhood. When I was her age I dressed in much the way she does, but only when I could steal away from my life as a boy. I dined, shopped, took classes, was romanced, and even found temporary work as a young woman—but unlike Laura, the demands of society and of my parents would eventually yank me back.

Synopsis (Spoiler Warning!)

Synopsis

Laura Ann Sykes (who was was first written in 1991) may be the first truly sympathetic transsexual main character in English-language fiction. Like real transsexuals, she isn’t a living stereotype. She isn’t whiny and frustrated, like the protagonist in Geoff Brown’s I Want What I Want, and unlike Roberta Muldoon in John Irving’s The World According To Garp, she is not a man who became a rather unconvincing woman. Rather, thanks to her Better-Living-Through-Chemistry program (she started taking her mother’s estrogen tablets when she was thirteen), Laura Ann considers herself to be a physically and emotionally normal seventeen-year-old girl with a “problem” of anatomy. Only those who remember her past—and an otherwise lesbian relationship with Mary June Cunningham—remind her that she is”…the only one I know who has singlehandedly turned herself from a boy into a girl. Laura Ann Sykes, Nobel winner in the new category, Self-Initiated Sex Change. Thank you, thank you.”

Those closest to Laura—her family, her lover, one of her teachers, and especially her schoolmate, Johnny Ray, who has seemingly dedicated his life to making her miserable—reinforce the notion of her former status as a boy, something Laura Ann would rather forget. She lives a nightmare life, looking and acting like a girl, yet being treated as a boy by people who insist on calling her Leroy (her former name). She is tolerated, but not accepted, in her small Southern town.

Laura Ann’s parents, at the suggestion of their physician, regularly send her to see a psychologist who suggests that she begin a manuscript in order to explore her feelings about having sex reassignment surgery—i.e., getting rid of her “problem.” This manuscript becomes the text of The Problem.

To keep him in line, Laura Ann has been surreptitiously giving Johnny Ray estrogens for two years. This has resulted in feminizing changes in his body, which he is attempting to hide by gaining weight. Laura’s cutting remarks about his masculinity precipitate a crisis (he attacks her in the lunchroom), and he and Laura are suspended from school. He manages to get Laura Ann fired from her job as a waitress, and her parents kick her out of their house. Johnny Ray kidnaps Mary June and takes her to Atlanta, where they become involved with criminals.

Laura Ann and her companions—Bobbo Joe, a practical-joke playing Native American and Tammy Mae, her eight-year-old sister (who stows away in the back of her car)—follow Johnny Ray’s trail to Atlanta. There, Laura Ann brashly and recklessly proceeds to bring to justice some really hard cases in order to rescue her girlfriend, and becomes a bit of a celebrity in the process. With some unwitting help from Mary June, she resolves her conflict about her “problem.”

Laura Ann is a strong-willed individual. Perhaps the reader searching for signs of masculinity in her will find it here, but they will have to be thinking in women-are-weak stereotypes. Bright and resourceful and creative, she copes well with an unsympathetic family and town and a life as something of a superwoman (student, housekeeper, wage earner). Her one blind spot is her inability to admit or even conceive that she is anything less than a true woman. She is unable to even bring herself to say the word “transsexual”—she calls it “the T word.” However, by the end of the book she has come to embrace her transgendered nature and realize that gender lies between her ears and not between her legs. She does, however, eventually decide to have sex reassignment surgery, and, at book’s close, explains why she made that choice.

At a time in which society is coming to realize how restrictive gender roles stifle all of us and how those who dare to be different have historically been mistreated, Laura Ann puts a human face on transsexualism.]

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

Doc Symmons told me I should write everything down. “Don’t worry about the grammar, Laura Ann,” he said. “Don’t worry about the spelling. Don’t go worrying about getting everything just so-so. Don’t try for the Pulitzer. Just make sure you get everything on paper. You don’t have to show it to me or anyone else. But it would be a great tragedy if the world were to miss out on your story.”

He was kidding, I think. About the tragedy, I mean. With Doc Symmons, it’s sometimes hard to tell.

Doc is small‑town crazy, which is more acceptable than big‑city crazy, so he’s let to run around loose, and shops at K‑Mart and everything‑‑ although maybe he should be the one on the couch and I should be pretending to listen to his woes, instead of he pretending to listen to mine. But he’s the one with the fancy office in the mall towers and a hennaed receptionist he shares with the rest of the doctors in the suite, and I’m the one who has to work her skinny butt off to make ends meet. Even though I’m normal and Doc is as looney as the Cocoa Puff bird.

Not that Doc isn’t good at what he does. No, even though he’s what Bobbo Joe calls a talkin’ doctor and not a doin’ doctor, he’s worth what he charges, for he’s helping me come to a decision about my “problem.” Besides, on account of my folks don’t make much money, Doc has me on a sliding scale, and I’ve yet to have to pay him his one-hundred-twenty-five-dollar-an-hour fee. By the time that hotsy‑totsy redhead finishes punching a bunch of numbers into the computer on her desk, I owe only twelve dollars and fifty cents. I don’t know where the rest comes from. Out of the redhead’s pocketbook, I would guess, from the expression on her face.

I’ll bet she isn’t red‑headed you‑know‑where.

I’m in the bathtub. Now, that may seem like a strange place to start a manuscript, but according to Doc, the tub is the only place where I come face‑to‑face—in a manner of speaking—with my “problem.” It seems as good a place to begin as any.

You’ll notice I put quotation marks around the word “problem.” I’ve noticed writers do that when they use a word that doesn’t really fit what they’re trying to say. I used quotation marks because I’m still not sure I do have a problem. Everyone else thinks so, of course, so indeed I may have a problem, with no quote marks.

My Problem stares at me with its Cyclopean eye. That’s the way I’ll start off when I revise this. This draft will never do, for I’m putting things down as I think of them; I’ll need to go back through and decide what will stay and what will go and make things more literary, and use my best penwomanship, so everyone will think I’m sophisticated. Besides, the notebook is damp from the humidity. The steam makes the paper wrinkle and the ink run.

My Problem stares at me with its Cyclopean eye. It is a problem (or a “problem”) of anatomy, but one that is really irrelevant except to me and those with whom I choose to share it. I mean, it’s ordinarily covered with clothing, and to look at me, you would never every suspect I had it. Yet, it’s surprising how everyone is so preoccupied with (Doc might say “fixated on”) my Problem. People who have never seen it and will never, ever see it seem to think it’s the most significant thing about me instead of the hormone-shriveled little thing it really is.

Doc has never laid eyes on it. Like the others, he takes it as a matter of faith that it exists as part of my body. Most of the people who are so worried about it have never beheld it. In fact, in my entire life, fewer than a dozen people have seen it.

No, that’s not true, for I was forgetting about that wretched episode last summer at Job Camp for Girls, when everyone up to and including the Lieutenant Governor had to come take a gander at it, once it was so-to-speak exposed. But aside from that, only the doctor who delivered me, and I guess his nurse, and my ma and my pa and my three older sisters. Maybe a baby sitter or two. And of course, Mary June Cunningham.

And then there’s Johnny Ray, with whom I played doctor when I was five and he was six—at his insistence, I might add. Now, one might think I would have been inclined to play doctor with a little girl, since I was supposed to be a boy, but I considered myself a girl and not a boy, despite everyone’s insistence to the contrary. I had seen my mother’s and I seen my sisters’, and I had changed my sister Lucinda’s baby girl’s diapers. No, I had seen little girls. What I hadn’t seen was a little boy’s, and when I saw Johnny Ray’s and realized his was the same as mine, I knew something was bad wrong. It made me want to throw up, realizing maybe what everyone had been telling me was true, and I was a boy after all. It didn’t help matters when Johnny Ray’s Pa caught us red‑handed, for he took us to my ma and pa and Johnny Ray and me both got called perverts and threatened with hellfire and eternal damnation for our immortal souls.

That episode didn’t affect Johnny’s life very much‑‑ it didn’t seem to, anyway‑‑ but it sure as hell put a brand on me. If Pa hadn’t much use for me before, he had even less after Albert Ray, standing in our front yard in a sleeveless t‑shirt which exposed the tattoos he had got in Singapore when he was in the Navy, worked up a good sweat swearing about our perfidious behavior, for which, of course, I was blamed, even though Johnny was the instigator. Now, Johnny Ray’s daddy had no room to talk, for I found out years later that tattoos notwithstanding he was a closet case himself. Neither did Pa, who was not exactly famous for keeping his pecker in his pants either. But with them against me, and with Johnny insisting I had made him do it, and with my very demeanor shouting deviancy at them, it was little wonder it was me and not the perfectly masculine little Johnny Ray who was blamed, who was damned forever after in the eyes of my father, that self-proclaimed man of men.

My Problem rarely shows itself these days, keeping itself tucked firmly out of harm’s way, except for those rare occasions when I forget to take my hormones and biology begins to reassert itself and I get testosterone in my system and it stirs about and threatens to rise to the attack.

I’d better rein in here and circle my horses. I mean, I need to put first things first. My name is Laura Ann Sykes. It is also Leroy Amos Sykes. I was born with the second; I go by the first. I have the looks and demeanor and disposition of a Laura, and I have the history and sex organs of a Leroy. I am unfortunately still legally a Leroy. I’d like to file a petition for name change, but Judge Crater, who is a great-great-great-great grandson of the Judge Crater who disappeared back in the nineteenth century, wouldn’t sign it because of that time out on the lake when he had a sudden attack of the middle‑age crazies and tried to get my britches down and I got mad and grabbed the paddle and chased him right out of the boat. Besides, it wouldn’t be legal, because I’m still nearly a year away from my eighteenth birthday and am legally a minor.

My life is miserable because I’m stuck somewhere between being a girl and being a boy. I live in a small town where everyone knows everyone else, and I just can’t seem to escape my past as a boy, even though I’m now a girl. My family calls me Leroy and my friends mostly call me Laura. At school I get called Laura and Leroy and sissy and faggot and queer and every other name in the book.

No one would ever suspect there is a Leroy somewhere under my skirts, for I am five‑six, with a good figure. I have big blue eyes and long brown hair and a pretty face and a soprano voice—well, more like alto. Thanks to the miracle of science, everything about me is just what you would expect in a seventeen‑year‑old girl. Except for the Problem. I make a point of not telling folks about it, but they find out soon enough, for I’m a major topic of conversation in a town hungry for gossip.

People who don’t know about my past as a boy treat me like they would any other girl. Once they find out it’s as if a shutter rolls down over their eyes, and they act differently towards me. Women get funny about me using the ladies’ room, and men get distant. The guys who have been attracted to me tend to cause trouble. More than once I’ve had boys become ugly with me after they found out.

Johnny Ray, having learned nothing from that experience so many years ago, is still exposing me. I think he follows me in his car, awaiting an opportunity to reveal my Problem and endanger me. It happened as recently as last Saturday. “Yep,” he said to my date of the evening, while I was in the ladies’ room. “Leroy sure do make one good‑lookin’ girl, don’t he?” When I got back to the table, my date was gone. No explanation, no nothing. He was just gone. He didn’t even settle the check. I paid it without complaining; it was better than sticking around and making a scene. The waitress, who had until then been all sweetness, stared at me. She looked as if she wanted to say something unkind, but I was mad enough to chew nails, and I guess she could tell it, for she kept her big mouth shut.

I know Johnny Ray was responsible, for as I was walking to my car he drove up in his Volkswagen, staying just out of grabbing range, and stuck his head out the window and told me what he had done.

Ever since he and I played doctor‑and‑nurse in the ravine, Johnny has been fascinated by me. He has always stared at me as if I was a snake or something. In grade school he would sit one row over and one desk behind me, and I would feel his hot eyes on me throughout the day. He has become more and more hateful of late; in fact, it got much worse about the time I became a girl. Although I have never done anything bad to Johnny (not counting the milk, which I did only in self‑defense), I have become his enemy, and he my nemesis. If not for Johnny continually reminding everyone about my Problem, I believe most folks would forget about my past or at least forget to remember about it and accept me as a girl.

Johnny Ray and Doc Symmons are typical of this town. I don’t think there’s anyone hereabouts who could be called really normal. Mom is a hypochondriac, an over‑the‑counter painkiller junkie, a woman who lies in bed surrounded by empty cans of Diet Coke and unfolded BC and Goody’s and Stanback powder papers, attempting to run the household by sheer vocal power. I’m her favorite target and “Goddamn it, Leroy” her three favorite words. She calls me Leroy and not Laura and “he” and not “she” but gives me pure‑D hell if I don’t get up supper and don’t keep the house clean enough to suit her.

Pa is a long‑haul driver, a man proud of his conquests of late middle‑aged waitresses at truck stops in places like Iowa and North Dakota. He’s even proud of the trouble he’s having with what he calls his prostitute gland. He considers it a manly disease, unlike that of his brother Bob, who had breast cancer. It was a source of amusement and bemusement to Pa until Bob ruined things by up and dying of it.

Lucinda, Marinda, and Clorinda, my older sisters, are, I swear, the three evil stepsisters from Cinderella. I used to wish my fairy godmother would arrive and save me from them, but what actually happened was they grew up and got married and moved out on their own. They bother me now only on occasion, when they visit. Tammy Mae, my other sister, is the youngest of five girls, although some would say four girls and one boy. She showed up unexpectedly when I was eight years old. I keep halfway expecting Ma to make love to Pa in a big pile of pain‑reliever papers and pull another baby out of her hat, but of course she can’t, on account of when Tammy Mae was born they took out her parts, for which I am thankful because if they hadn’t I would no doubt be a boy now instead of a girl. I know on the face of it that statement might not seem to make much sense, but it’s true.

Tammy, precocious child that she is, has a lesbian crush on me—much to my chagrin, for my lesbian relationship with Mary June Cunningham is more than I can handle. “Get rid of your Problem,” Tammy cooed to me last week. “Get rid of it, and we’ll run away and leave this crazy place and be just two girls in an exotic land.” I told her to cool it.

I would like nothing more than to be rid of my Problem, which I consider nothing more than a tumor, but Mary June is fascinated by it, and I just know she would leave me if I got it cut off, even though it mostly doesn’t work. I’m hanging onto it for her, although having it makes it sort of hard to have a normal lesbian relationship. Doc Symmons says there’s no hurry, that I should do what makes me happy and not live my life for anyone else—even Mary June. It’s to help me decide what to do about my Problem that he told me to write all of this down.

My Problem stares at me with its Cyclopean eye. Little Leroy Junior. Out of sight, out of mind. I get out of the tub, and dry off. I tuck him away and pull on my white uniform and go out the door to work, to the truck stop, where a thousand carbon copies of my pa wink at me and ask me out and try to get me interested in their Problems.

Chapter 2

Chapter 2

All dressed in white, starched, clean, I look like a nurse. White shoes, white stockings, white dress. White panties, white bra. White. I feel pure and clean. I want to minister to the sick, to wipe sweat away from fevered brows. What I do is slop the hogs. By the end of the shift, the white will be marred by gravy and ketchup and thousand island dressing stains. I’ll go home smelling like a hamburger. I’ll make everyone hungry. “Damn it, Leroy,” Mom will yell. “Git out of that waitress dress and into a pair of britches and take that makeup off. It makes you look like a tramp. And get busy in the kitchen. Your Pa will be home any time now and he’ll want his supper waitin’.”

But that’s tem hours away. Today, Saturday, is my favorite day at the truck stop, because I start with the sunrise, pushing coffee on bleary‑eyed truckers and the breakfast bar on blue‑haired ladies on the way to Florida with their bald‑headed husbands. The new hot bar takes most of the work out of breakfast. It’s a wonder the way folks put it away when they pay six ninety‑nine for all they can eat. They got to get their money’s worth. They go right for the high‑cost foods, too, piling strips of bacon high on their plates, lining link sausages up like sardines, stacking slices of ham, peppering their eggs, ladling gravy over sausage patties, smothering their pancakes with syrup and butter, coming back time and time again to fill their tiny glasses with orange juice. They load themselves up with cholesterol and starch and fat and sugar and caffeine until I wonder how they make it to the cash register without having a stroke or a heart attack.

Except for keeping coffee cups filled, there’s not much to do during breakfast but keep the line stocked and clean up after the messiest eaters. I’m not allowed to ring up customers on account of I’ve not been here six months yet. It’s the third truck stop I’ve worked at, the third truck stop I’ve had to work at. I keep ranging further afield as rumors of Leroy, Jr. keep pursuing me, with Johnny playing the part of the winged messenger.

After what happened on Tuesday evening it seems unlikely I’ll ever be ringing up customers here. And this time, it wasn’t even Johnny Ray’s fault. I was in the walk‑in cooler, reaching for a tray of sliced cucumbers for the salad bar when I got grabbed from behind. It was Mr. DiPoulo, the area supervisor, a dirty little old man from Greece who thinks too much about what is in the waitresses’ pants. Not that we wear pants. We wear skirts, which is why he got more than he bargained for, for when he reached under mine, he encountered my infamous Problem. Now, I’ve learned from experience most men don’t really care‑‑ not so long as they get theirs, if you know what I mean‑‑ but Mr. DiPee, he just backed away with this frightened look on his face. I half‑expected him to make the sign of the cross at me, as if I were a vampire or something. He just stood there white‑faced, and I said, “I won’t tell if you won’t,” and he gulped and nodded his head and reached behind him and got the door of the walk‑in open and slipped out. He won’t say anything to anyone about my Problem, but I know how things will work out. The manager will start finding fault with little things I do, or maybe I’ll be blamed for something I didn’t do, and I’ll be looking for a job again. It’s happened before.

Bobbo Joe, the short‑order cook, has a permanent hard‑on for me. Maybe it’s just that he has a permanent hard‑on and it’s usually pointed in my direction. He’s furiously jealous of the truckers who call me Hon and leave big tips and pinch my fanny every now and again. When he thinks a driver is getting fresh, he puts Visine in his food, which causes the driver great distress a hundred miles down the road. Bobbo would lose his job if Mr. DiPoulo or Murray the manager found out what he’s doing. But I don’t tell and Bobbo doesn’t tell, and the truckers don’t associate being sick with what they ate‑‑ or at least don’t figure out they’ve been Visined, for if they did they would drive their rigs back to the truck stop and pound the shit out of Bobbo Joe, who, although he stands six feet and four inches tall, would probably just stand there and let them kick his Indian ass.

I make lots of tips working here on Saturday and Sunday and three nights a week. I’ve filled all the drawers under my waterbed with quarters and half‑dollars and dollar bills, and I have more than four thousand dollars in a CD account. It’s my surgery money, my kitty account. I probably have almost enough saved to do something about my Problem, except I’ve put plans on hold in that department on account of Mary June Cunningham.

You’ll notice I’ve been capitalizing the word Problem. Sometimes writers do such things. I like it better than the quote marks, so whether I’m speaking of it as my problem or as my “problem,” from now on I’ll call it my Problem.

Anyway, I could go overseas for surgery (it’s cheaper there), and then I would be a whole woman, but if I did then M.J. would leave me and I would be heartbroken. I love Mary June and she loves my Problem. She wants it to get big and hard so I can push it into her body like a man pushes his into a woman. Because of the hormones I take, that isn’t going to happen, but sometimes it does stir around a bit, and it gets her all excited. I don’t like her touching it. I don’t touch it myself‑‑‑ after all, it’s not supposed to even be there—but I love M.J. and want to make her happy, and so I let her do what she wants with it, even though I hate it and wish it were gone.

I can’t believe I’m writing this down. It’s so gross.

All the rest of the time except when Mary June is trying to get me to use it on her, I wish the Problem was gone. I push it up into my body, but it always pops back out. I wish it would screw off so I could keep it in my pocketbook along with my keys and compact and mascara and wallet. I wish that when Mary June wanted it, I could just dig it out of my purse and go into the bathroom and attach it.

Well, there’s one other time when I would wear it, and that’s when I am in the woods and there isn’t a toilet handy. I would wear it then. And maybe, just maybe, I would put it on in secret every now and again, just because the way I look I’m not supposed to have it. And if it would get big and hard, maybe I would whip old Leroy, Jr. out every once in a while and shock the church ladies. Maybe I would show it to Bobbo and tell him it just grew there overnight. Maybe I would let the next truck driver who tries to feel me up put his hand there and get a surprise. Maybe. But mostly, it would just sit in my purse, awaiting a legitimate use, and I would have the other thing, the female thing, all the rest of the time. And I would use it, too.

At eleven o’clock, I tear down the breakfast bar and set up the salad bar. You wouldn’t think truckers would be such big eaters of greens. It makes me smile to see a two‑hundred pound man making a meal of lettuce and radishes and bean sprouts.

You wouldn’t think truckers would be romantic, either, but they are, some of them. Archie Mann, who hauls screen doors from Gary, Indiana to Hollywood, Florida, brings me a red rose every time he comes through on the way south, and a white or yellow one when he comes through on the way north. He wants me to go out with him, but I’m afraid to on account of incompatible anatomies. The Problem, raising its ugly head again. Its Cyclopean eye. God only knows what he would do if he found out, but something tells me I would get no more flowers. So I just smile and take the roses and give Gary, Indiana a hug, being careful to keep my chest a handsbreadth from his so he won’t get any ideas, and thank him, and three days later, he’s back with another rose. I don’t know, maybe the hug keeps him going. The roses sure help me keep going.

A florid‑faced, bald‑headed married man from Oregon is flirting with me, telling me I’m pretty, hinting he has something to show me up in the sleeper of his truck. Bobbo Joe isn’t missing a thing, and thirty minutes from now that trucker will be looking for a commode. Not knowing this, he shovels down his spaghetti and meatballs and tetrahydrozoline and winks at me. Bobbo stands in the kitchen with his hands out of sight and looks at me through the food window. He holds up a paper plate. A severed finger lies there, gore trickling out, only it’s not gore, but cocktail sauce, and the finger, which is sticking through a hole he has cut in the plate underneath all that cocktail sauce, is still securely attached to Bobbo’s hamlike hand.

Bobbo has a bag of tricks like Felix the Cat’s. You wouldn’t think about a native American being a practical joker, but he’s the world’s worst. He’s only been had once, and that was by Murray Lockett, the manager, on payday about a month ago. Bobbo had a new trick, and he was trying it on everyone. He would ask someone to get out a dollar bill. They would, and he would tell them to find on it the name of a famous movie and a brand of cigarettes. When they gave up, he would grab the dollar and tear it in two and holler “Half and Half and Gone With the Wind” and toss the pieces away and laugh like a hyena.

After a dozen employees and customers had come to Murray to borrow the Scotch tape to hold the torn halves of their dollars together, he asked someone why they wanted the tape and discovered what Bobbo was up to. He’d waited until payday, and then cashed Bobbo’s check, like always. Bobbo had clocked out and gone in the bathroom to fix his duck-ass, leaving his jacket on the counter, which is his usual habit. Murray picked up the jacket and got Bobbo’s wallet. He took out a twenty dollar bill and told me to go to the cash register and get twenty ones. I hurried so Bobbo wouldn’t be out of the necessary room before I returned‑‑ not that there was much danger of that, ’cause friend Bobbo has a twenty minute DA; he stays in the bathroom for the longest time, getting it just right. Murray took all those one dollar bills and put them in the money clip in his front pocket and took off for the dining room.

Bobbo came out of the bathroom and was putting on his jacket when Murray came rushing into the kitchen and said, “I hear you have a trick, a good one. Show it to me.” Bobbo said sure, give him a dollar. Murray did, but when Bobbo got to the part when he says “Half and Half and Gone With the Wind,” he stopped and told Murray he just couldn’t do it to him. Murray waved his hand impatiently and told him to go ahead, if it was a good trick. Bobbo hesitated, then tore the dollar apart and threw the halves away and laughed like a fool.

Murray‑‑ and this is the part that killed me, only I couldn’t laugh, ’cause Bobbo would have known something was up‑‑ Murray just stood there looking puzzled and then shook his head and said, “I didn’t quite get that. Show me again,” and took another of Bobbo’s dollar bills from his money clip. Bobbo pointed at the two halves on the floor and asked Murray if he wasn’t going to pick them up and Murray shook his head and said, “Later. I’m concentrating on learning this. Here. Show me again.”

Well, Bobbo stood there tearing up dollar after dollar until there was a big pile of paper on the floor, with Murray saying, “One more time. I think I’ve almost got it.” When Bobbo tore up the last bill, Murray just turned and walked away. Bobbo hollered after him. asking if he was going to pick up his money, but Murray just kept walking.

Well, when I told Bobbo whose money he had torn up and thrown all over the kitchen, he went pale under his red skin. He was so shook up that if I hadn’t of helped him match them up, he would have never got those dollars all taped together. Then, to make matters worse, he tried to pay for some coffee to go with one of them and Murray came to the register and told him he couldn’t take that dollar as there appeared to be something wrong with it and it might be counterfeit.

Bobbo couldn’t get back at Murray on account of Murray being the boss, but he was mad at me for standing there not saying anything. One night about a week later, he kept disappearing. No one seemed to know where he was going. When I got off at midnight, I found out what he had been doing. He had gone outside maybe four or five times an hour and thrown a five‑gallon bucket of water on my car‑‑ which would have been no big deal, except it was January and about five degrees below zero. When I went outside to go home, the tires were bulging from the weight of the ice and I couldn’t get the key in the door. I had to carry bucket after bucket of hot water outside and empty them over the door until I could get the key in the lock and get in the car and start it. While it warmed up, I sat in a White Freightliner with a man called Max and let him play with my breasts. I told Bobbo about it the next day, but it was too late for the Visine, as Max was about four states gone by that time.

I wonder what Bobbo Joe would do if he found out about Leroy, Jr.

Chapter 3

Chapter 3

School is okay because I spend most of the day in a gifted program, studying science and math and art and stuff. They tell me I’m a genius, and I suppose maybe I am, for I’m the only one I know who has singlehandedly changed herself from a boy into a girl. Laura Ann Sykes, Nobel winner in the new category, Self‑Initiated Sex Change. Thank you, thank you.

In most of my classes I am allowed to be a girl. I’m not supposed to wear skirts or dresses, but I started in my junior year, and no one seemed to mind. But Leoretta MacKenzie, my English teacher, is such a bitch. She makes me change to slacks when I come to her class, and calls me Mr. Sykes. She’s got no eyebrows. I mean no eyebrows, just some black pencil marks, or maybe it’s a tattoo. It’s too weird.

“Please read your poem aloud, Mr. Sykes,” she says. A loud snicker comes from Johnny Ray’s direction.

“Mr. Sykes!” she snaps. I blink my eyes. “I’m sorry, Miss MacKenzie,” I say. “I didn’t realize you meant me.” It was halfway true. As I don’t fancy myself much of a Mr. Sykes, the name just sort of washes over me without sticking. Miss MacKenzie is aware of this, and she knows using the name Laura Ann will get my attention right away, but she has some sort of moral compunction against calling me by my rightful name. She was so hateful on the first day of school that I showed up the next day with my eyebrows shaved off and drawn on with black pencil just like she does and my hair up in a bun like hers and she dragged me down to Mr. Mendez’s office on account of it. Mr. Mendez is the principal and he looked at me and then at Miss MacKenzie and then at me again. “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” I said, and got sent home for three days. MacKenzie has had it in for me ever since, and so I get picked on a lot in her class. Today, she tells me to read the poem I picked for the class assignment.

I’ve picked a poem I know she will hate. “I have seen the best minds of my generation…” I begin, and she goes white underneath her warpaint.

“Stop!” she cries, and I know I’m one step away from saying hello to Mr. Mendez. “I won’t allow that filth read in class!” She snatches up the little red book and waves it in the air. “This poem,” she tells the class, “was written by a homosexual man, a pedophile, a degenerate who was taken to court on obscenity charges.”

“He won the case,” I say dryly. “The name of the poem is ‘Howl,’ by Allen Ginsberg,” I add, so everyone can write it down and try to find a copy as soon as school is out. “I got it at Mills Bookstore.”

“Mr. Sykes,” Miss MacKenzie says frostily, “Please accompany me to the principal’s office.”

“You wouldn’t like the ending anyway,” I tell the class, flipping my hair, and go with her.

Mr. Mendez is not happy to see me, but he won’t suspend me or try to turn me into a boy, for we’ve come to an agreement of sorts. “Miss Sykes,” he says, after the MacKenzie has run down, “you will remain after school for one hour every day this week and next.”

“His name is Leroy, Tony,” says Miss Mac. “Calling him Laura or Miss Sykes is giving in to his delusion that he’s a girl.”

Mr. Mendez glances at three boys from shop class sitting uneasily in folding chairs in the waiting area. They are there to present him with a lamp made from a bowling pin. Every year the shop class hits up the bowling alley for pins to make into lamps, and they always present one to Mr. Mendez. He could probably stock his own bowling alley. He gets up and pulls his office door closed so the shop boys won’t hear. “Damn it, MacKenzie, this child is not psychologically a boy. He’s been dressing like a girl all through high school. For better or worse, in three months she’ll be out of here, graduated, and it will be with honors, I might add. It serves no purpose to cause her distress by refusing to call her by the name he chooses‑‑ I mean, she chooses.”

Mr. Mendez is not naturally so liberal; he comes about his opinions the hard way. On the first day of the ninth grade, I found myself in his office.

“Very clever disguise, Sykes,” he said to Elizabeth Fenner, who was there to see him about working in the school office. Liz turned white and gave a sort of sob and ran out into the hallway.

“I’m Laura Ann Sykes,” I told him.

He stared at me and then took me into his office and pulled the door to. “Your name,” he told me, “is Leroy Sykes.”

“Legally it may be Leroy,” I said. “That’s only because I’m not old enough to change it legally. My chosen name is Laura.”

“Be that as it may, and regardless of what they let you do in junior high, you will dress as a boy at all times. Trousers. Shirts. Socks. You will wear no makeup. No jewelry. I’m not going to make you cut your hair, but I do expect you not to tease it up so. You’ll use the boys’ bathroom. You will take physical education with the rest of the boys.” He looked at my folder. “Scratch that. I see you’re down for swimming instead of gym. You will wear a boy’s bathing suit. You will use the boy’s locker room. Do you understand me?”

I snapped my bubble gun and bent over and ran my hand lightly up and down my stockinged calf the same way I had seen Andrea Ammonds, the school tease, do. The effect was not wasted on Mendez. He swallowed hard and tugged at his collar. I straightened up and looked at him coolly. “Mr. Mendez, let me make something clear. There is only one part of my body that makes me a boy. I look like a girl without makeup on. Without jewelry. In boy clothes. I sound like a girl. I smell like a girl. That’s because I am a girl.”

He continued to look uncomfortable. “Nevertheless, you will do as I have said.”

I grinned at him. “The boys’ bathroom?” I got up and opened the door that opened directly into the hall and made a clucking sound at two boys who were going by. They stopped and stuck their heads into the office. “Mr. Mendez tells me I gotta use the boys’ bathroom. Either of you interested in comin’ along to see whether I’m a pointer or a setter? After that, we’ll run along to the gym and you can see me in the pool, topless. I got real titties. I might let you touch them.”

They grabbed my arm and started to hustle me off down the hall, and two boys from the football team, who had overheard, came along behind. That did it. Mr. Mendez ran after us and grabbed me and brought me back into his office. He and I had obtained an uneasy truce that day; I was allowed to be me, so long as I did not actually wear a skirt or a dress and wasn’t deliberately outrageous with my makeup or hair or behavior. I was not to use either the boys’ or girls’ restrooms; instead, I was given a key to the faculty lounge so I could use the one-seater in there. All-in-all, I couldn’t have asked for better. Sure, he had sent me home for three days for sassing Miss MacKenzie, but that was because of my smart mouth and my cheap shot at her. For the most part, I had lived up to my end of the bargain (except that I did wear skirts), and he to his. Now, he was reading her the riot act.

“Leoretta, it avails us nothing to persecute this child. Please take her back and try, just try, to teach her a little English. Call her by whatever name she wants. It won’t hurt anything. Be a teacher. Teach. And you‑‑” he looked at me heavily‑‑ “If I hear of you doing anything else to antagonize Miss MacKenzie, I will require you to cut your hair before returning to school.”

Well, I could have had it lots worse. Having to stay after school is no fun, but it beats having to explain to Pa why I got suspended. Pa can be a liberal man with his belt or a razor strap.

Every day at lunchtime Johnny Ray sits down across the table from me and eats his food and part of mine. He’s done it since third grade. His Jetsons lunch box long ago gave way to an Igloo Lunchmate which would hold even Jethro Bodine’s meal. Johnny is a big eater‑‑ he was even when we were playing doctor in the ravine behind the playground. At five‑seven and nearly three hundred pounds, Johnny has turned into a real four‑by‑four. He was always chubby, but something has happened in the past year or so to make him puff up like a marshmallow man. It’s my fault he’s as big as he is, and if he should up and kick off like Uncle Bob, why, I would feel right guilty about it.

Johnny Ray is just a miserable person. He could sit anywhere in the lunchroom, but he delights in tormenting me, keeping my friends away. Yes, I do have a few friends. I think he lives vicariously through me, for he always wants to know who I’ve seen and what I’ve done. And about two years ago, he turned even more nasty‑‑ his interest took on more overtly sexual overtones. He stared lurking about in the bushes and jumping me and trying to pull my clothes off, and nearly succeeding. That’s when I decided I had to do something about him.

Johnny looks at me like he looks at other girls, but he calls me Leroy. He gets worse and worse. “Howdy, Lee‑roy,” he says now. “That big Injun got any idea about the surprise you keep in your pants?” His cheeks are rosy, like two apples. He keeps his hair cut short in a burr, but he is looking more and more like a girl. It worries him, and it’s why he’s getting so fat‑‑ to cover up his breasts, which came out of nowhere last year and which keep getting bigger and which embarrass him to death in gym class.

Johnny eats fast, all business. As he has done every schoolday since we were in the third grade, he picks up my carton of milk and drinks it dry. He’s always messing with my food, too. Today he reaches into my salad and picks up a piece of carrot and licks the ranch dressing off it and puts in his mouth like a cigarette, then flips it with is tongue. I push the plate away from me with both hands, and he falls to, devouring what I’ve left unfinished.

I sigh. If Johnny has discovered where I work, he’ll have spread the news about my Problem. I dread the thought of going to work and facing the music. “That’s between me and Bobbo,” I tell him.

“That boy got some kind infatuation with you,” Johnny leers.

“Don’t you dare be hanging out at that truck stop,” I scold him. “I’m already driving far enough as it is without you getting me fired so I’ll have to go further.”

“Them semi drivers,” he muses. “Do they kiss on you and stuff?”

“Johnny Ray, you mind your affairs and I’ll mind mine.”

“Do you play with your titties?”

I look at him. “Do you play with yours?”

That gets him. He turns red in the face and gets up and staggers off.

Johnny’s mother has had him to the doctor, who can’t figure out why he’s developing in the way he’s developing. I know; the reason is in my purse.

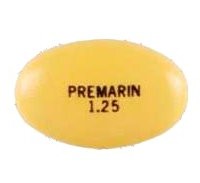

When I was thirteen years old Ma started having hot flashes. It was a miserable time around the house, with her bitching and moaning and telling everyone how lucky men (meaning me and Pa) were to not have to worry about the change of life. Doc Johnson put her in the hospital and took out her female organs and ordered up some little football-shaped pills for her. Since they weren’t pain pills and didn’t do anything for her nerves, she soon forgot about them— but I knew they were female hormones. I went to the library at the state university and found a big reference book that told about all kinds of medicine and read up on estrogens and what they did, and I knew I had to get some. I was carrying one of her pills in a baggie in my pocket so I could match it up with the pictures in the book. I went right into the mens’ room and into the stall and sat there and swallowed that pill. My hand was shaking so badly I almost dropped it.

About a month later I took the empty bottle to the pharmacist, and he refilled it. After a while, I guess, he knew it wasn’t Ma who was taking the pills, but he didn’t say anything; he just kept refilling the prescription, even though I was taking about four times more pills than Ma was supposed to. He still refills them for me. We have a don’t ask, don’t tell sort of relationship, I guess.

It was difficult to find money to keep myself in medicine, but after I ran out and the physical wheels started spinning in the opposite direction, towards manhood, and I started getting hairs on my face, I managed to find the money. Mostly, I babysat or did housework, but I’ve not been above mowing yards or weeding gardens or doing other hot and sweaty work to pay for the magic I found in that bottle. When I turned sixteen I went to work as a waitress, and that solved my money problems.

Now, thirteen year‑old‑boys don’t look all that different from thirteen‑year‑old girls, at least if they haven’t gone into puberty. I hadn’t. I had a high voice and not even a single pubic hair. Within a month or so after I started taking Ma’s pills, I went into adolescence, only it wasn’t boy‑type changes I went through, but girl‑like changes. Because of the way I’d dressed and acted and worn my hair, I had sometimes been mistaken for a girl, but six months after I started taking those pills, there wasn no doubt what I was. My hips swelled and my nipples got tender and I grew breasts and my waist drew in and I plumb turned into a young woman‑‑ except I had the aforementioned Problem. I had been hoping it would dwindle away and leave me with the other thing, but it persisted in staying the same while everything else about me was changing.

One night at the supper table I announced I had changed my name to Laura Ann and was now a girl. Pa leaned across the table and smacked me with the back of his hand and told me to go to my room. I lay on the bed and cried for a while. When I finally wound down, I sat up. There on my dresser was a paperback western Pa had finished and which I had taken to read. The cover showed a band of Apaches in warpaint, dancing around a fire. I stared at it for a long, long time, and then emptied the closet and the dresser, piling all my boys’ clothes, including the ones I was wearing, on the bed. I gathered everying in the sheet and tied the ends together and threw the bundle out the window. I jumped out after it, stark naked, and dragged it into the back yard and siphoned some gasoline from Pa’s Buick and used the Buick’s cigarette lighter to set a piece of paper aflame. I walked over and dropped the burning paper on the clothes, setting them afire. As they got to burning good, I started dancing around the fire, whooping like the Indians on the cover of that western, I was so happy. By the time Pa came running out of the house the flames were ten feet high. Everything was burned to cinders.

I got a good larruping, but the next morning, when I showed up at breakfast in a pink blouse and girls’ jeans (Clorinda’s castoffs), little was said. I never wore boys’ clothes again. Any that showed up I razored into confetti or burned. I would get whipped and warned never to do it again, but I continued, and after a while Ma stopped buying them.

Pa thrashed me when I got after my eyebrows, and again when I had my ears pierced, and more than once for wearing dresses and skirts. Ma threw away my hormone pills whenever she could find them, and once, when I was in the tenth grade, she snuck into my room and cut off all my hair while I was asleep, which just made me look like a bald‑headed girl. They had me to the family doctor, who was at a loss about what was going on and just said I must be a ‘morphodite, which I looked up in the dictionary and discovered I wasn’t. The principal of the junior high, from which I had been suspended for refusing to cut my hair, suggested they take me to Doc Symmons, the shrink, who I’ve been seeing ever since. That was all they could think to do, and at Doc’s recommendation, they let me back into school and have pretty much let me be a girl‑‑ not that they have much choice about it, ’cause I am what I am. Thanks to the little yellow footballs, it’s not really a question of what I wear, but of the girl’s body I’ve come to have.

It’s funny how people reacted to the change. Folks who I meet for the first time see nothing unusual about me and treat me like any other girl. When I went back to school after summer vacation, wearing a skirt and makeup and with my hair permed, people didn’t recognize me and assumed I was a new student. They were shocked when they found out who I was. I looked so much like a girl that even the ones who were hateful tended to pretty much forget I wasn’t. After a while, everyone took my appearance pretty much for granted, but most people who had known me before refused to call me Laura Ann or refer to me with female pronouns. Most of the new people I met couldn’t quite bring themselves to believe I had ever been a boy and called me by the correct name. I think things would have eventually worked out if it hadn’t been for the everpresent Johnny Ray, keeping things stirred up.

In my purse I carry a little mortar and pestle I borrowed from chemistry class. Every morning, just before lunch, I go into the stall in my special bathroom in the teacher’s lounge and take two of the little yellow hormone pills out of the bottle in my purse and grind them into powder and pour the powder into one of Mom’s Goody papers and fold it up. When I get to the lunchroom I empty the paper into my milk and stir it with my straw until it dissolves. As I’m finishing my meal, Johnny comes into the lunchroom and drinks the milk. Invariably. He never forgets. Five days a week, for more than a year now, he has been getting enough female hormones to grow tits on a boar hog.

Johnny Ray is going through the same physical changes I did, and it’s scaring him to death. He’s eating like a pig to cover up his chest, trying to keep anyone from finding out about it. He doesn’t have any idea why it’s happening. He hates it, but if he hadn’t started trying to rape me, I wouldn’t have had to put pills in my milk (which he has no right stealing, anyway), and he would grow up to be a man instead of whatever it is I’m turning him into.

I should probably hate myself for what I’ve done to Johnny Ray, but I don’t. He’s getting exactly what he deserves. It’s his just deserts for the miserable things he’s done to me over the years.