Are Transsexuals as Reliable as Other People? (1990)

©1990, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Sources

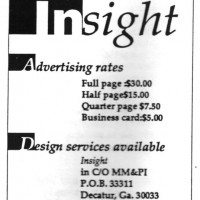

Denny, Dallas. (1990, Spring). Are transsexuals as reliable as other people? Insight, 6(1), cover, 1, pp. 5-6.

Denny, Dallas. (1990, Spring). From the director’s desk. Insight, 6(1), p. 1.

In the late 1970s I spent months wading through the medical and psychological literature of transsexualism. Transsexuals, the literature said, were dishonest, flighty, and unreliable, and were likely to have character and personality disorders.

I was shaken. I didn’t see myself in that description, and I wondered how I could be transsexual and yet a stable person.

We now know that literature was flawed and biased, grounded in a medical model that required that transsexuals be mentally ill. Needless to say, my thinking and language have evolved since early 1990, when this article was published. It does, however, accurately reflect the effect of the medical literature on my thinking more than ten years after my frightening immersion in that literature.

I was an editor of this issue of Insight, the newsletter of the Montgomery Medical & Psychological Institute.

Are Transsexuals as Reliable as Other People? (Text)

Copyright 1990, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Denny, Dallas. (1990, Spring). Are transsexuals as reliable as other people? Insight, 6(1), cover, 1, pp. 5-6.

Are Transsexuals as Reliable as Other People?

by Dallas Denny

Author’s note: The literature suggests that female-to-male transsexuals are in general more stable than male-to-female transsexuals. I have therefore geared the following discussion for the male-to-females (who would seem to need it). The examples in this article are fictitious, but are based on real life persons and circumstances.

Are transsexuals reliable? That is the theme of this issue of Insight. The question might as well be “Are relatives reliable?” or “Are politicians honest?” The answers, or course, are yes and no. We took a critical, yet (we hope) kind look at our paraculture, and frankly, while we found much of which to be proud, there is room for improvement. We hope our readers will engage in a moment of honest self-examination.

Recently, I visited a physician and requested of him a simple surgical procedure. He told me that because he had had so many bad experiences with transsexuals, he no longer provided the service I had requested. “it’s just not worth it to me,” he told me. “There were just too many problems. I’ve decided I’m not going to do it any more.”

I didn’t ask him exactly what the problems had been. I could guess: missed appointments, and unpaid bills, and perhaps unpleasant scenes in the waiting room. Whatever caused him to change his mind, he was unwavering; he would no longer provide the service. Neither would the second physician I contacted, and for the same reason.

Out of this experience was born this article: whether transsexuals are reliable. It is a question that, so far as we know, has never been addressed. It is an important issue, and, considering that we lost several valuable professionals in 1989, a timely one.

Martha was worried. Her electrolysis practice was not flourishing. The rent on her apartment was overdue, and she faced the prospect of an unpleasant confrontation with her landlord, for she was seventy-five dollars short of the full amount. Fortunately, she had appointments scheduled for one, two, three, and four o’clock, and if they all showed, she would have enough money to pay the rent and fill the refrigerator with groceries.

At one-thirty, her three o’clock phoned and canceled. Her one o’clock had neither shown nor called. When her two o’clock didn’t come, she shook her head in exasperation and wondered why she hadn’t gone into real estate like her mother had wanted. At four-fifteen, her four o’clock appeared and went immediately to the restroom, (where she spent five minutes) then asked for an aspirin, claiming she had a headache, and refused to start treatment until the aspirin took effect. After the session, she wrote a check which later bounced.

Two of the clients were male-to-female transsexuals, and two were genetic females.

On Saturday, a caller identified herself as transsexual. Martha referred her to another electrologist.

Transsexuals are a minority, and the general public has a perception of them, just as it has a perception of other minorities. That image is shaped by many things: By the general moral climate of the nation, by television talk shows, by articles in tabloid papers, by the media focus on “celebrity” transsexuals like Renée Richards, and by innumerable other factors. But transsexuals themselves, in appearance and behavior, do much to shape this image, and it is the purpose of this article to examine how transsexuals contribute to their public image.

The average American has never encountered a “real, live” transsexual, so when he or she does meet one, he or she is apt to attribute characteristics of the individual to the entire group. Such generalization is an all-too-common human failing, and one we won’t be rid of anytime soon. But we can try to ensure generalizations are positive rather than negative. Obviously, people will be favorably affected by reasonable, polite behavior and unfavorably affected by eccentric, bizarre, or tasteless behavior. That makes each and every transsexual an ambassador for the entire class, for the people she meets are likely to use her as a standard by which to judge other transsexuals. Unfortunately, there is as much variability in transsexuals as in any other group of people, and while the majority are reasonable, reliable people, some are not. There are people out there who have been burned, in one way or another, by transsexuals, and it will not be easy to change their unfavorable opinions.

Nurse Johnson stuck her head through the doorway and made a clucking sound. When Dr. Madison looked up she said, “I’ve pulled all the tardies and have them in the mail to go to the collection agency.” Her head disappeared.

A moment later it reappeared. “I was right. You know that patient I asked you about? The one I told you was a man? The one that made me so nervous? I told you you would never see any money from him. I don’t know why you see those people.”

The successful transsexual is invisible—so successfully integrated into society that her transsexualism goes unnoticed and unremarked—and any unusual behavior she may exhibit will not be attributed to transsexualism, but to other factors. It is the “clockable” transsexual and the transsexual who chooses to reveal herself who shape opinion. And to Everyman, one genetic male in a dress is the same as any other. Many who crossdresser are not (or are only marginally) transsexual. Heterosexual crossdressers (once called transvestites) are well-behaved, but their dress is sometimes fetishistic and most make no serious attempt to feminize their bodies (making them, as a group, easy to “clock”). There are also, of course, drag queens and cross-dressed prostitutes in profusion. A drive down Atlanta’s Peachtree Street in the wee hours of any Saturday morning, or a visit to a show bar will make this painfully apparent. The behavior of such individuals is generally unlike that of genetic females, being at best colorful and at worst highly obscene. Their dress is also unorthodox, being worn mainly for the purpose of attracting sexual attention. The high visibility and obvious maleness of this segment of the population cannot but negatively impact the opinions of at least the more conservative types who see them. And unfortunately, many true transsexuals more-or-less pattern themselves, in dress and behavior, after such “rude, crude, and lewd” people.

… While this individual is sometimes charming and overtly friendly, he tends to be impulsive, flighty, manipulative, and undependable. He is likely to make promises he doesn’t keep, and will often disappoint those who rely on him the most.

—Note from file of transsexual client of Dr. Amos Franklin

The very nature of transsexualism can make it difficult to behave in an ordinary manner, especially if the individual has not come to terms with herself. The transsexual is a poor psychic fit to her social role—she has a body she detests, and the demands made on her are keyed to that body and not the body and social role she feels she should have. Functioning daily in the wrong body is highly stressful, and can lead to depression, lassitude, and general lack of productivity, with the individual not really caring about herself, and perhaps sabotaging herself in subtle (or not-so-subtle) ways. Her actual wants and needs differ from those of the non-transsexual male. Her values are different. It is not surprising, then, that others may characterize her as deviant, that her behavior may to them seem strange or unfitting. How so? Well, she may pay little attention to her personal appearance and grooming, show little ambition or drive, be resentful or jealous of genetic females, or have difficulty in interpersonal relationships. She may engage in bouts of hypermasculine behavior in attempts to “prove” her maleness. She may mutilate her body or genitals. She may allow herself to become obese or painfully thin. Her behavior may vacillate as she moves in and out of the closet, with relatively “good” (i.e. normal) behavior at times when she is coping relatively well, and aberrant behavior when she is at her most conflicted. Feelings of guilt may be so strong as to impact her functioning. Guilt and vacillation can lead to on-again, off-again behavior—resulting in appointments that are not kept, promises broken, deadlines not met.

Transsexuals can find themselves with conflicting role expectations; their lives as women may be in direct or indirect opposition to their lives as men. Any feminization of appearance will of necessity lead to a less masculine appearance. Arched brows and waxed arms, feminine hairstyles, and estrogen-related somatic changes may result in problems in the masculine role—yet not making these changes is a denial of the individual’s inner self and will compromise the effectiveness of the feminine presentation. Changing social roles is emotionally jarring, and requires privacy and a certain amount of time for physical and psychic preparation. A transsexual may find herself with plenty of time to keep an appointment, yet insufficient time or place to dress—and even if it is possible for her to show up as a man, she may be unwilling to show herself as such in that situation.

There are also logistical problems. Ordinary avenues of access can be denied. If the individual cannot receive incoming calls at home or at work because of hostile or uninformed spouses, supervisors, or co-workers, she can be reached only by mail. And even written correspondence may be difficult, as the individual may not have a mail drop and may for reasons of privacy be unwilling to give out her address.

Ordinary avenues of help may be denied. Physicians and psychologists may be hostile, and, unless they have special training, are certain to be ignorant about issues of transsexualism. Friends and family may not know of the transsexualism, or, if they do, may be angry or indifferent. Clergy are not likely to understand or sympathize. Insurance and work-related support may deny coverage, or the individual may be unwilling to risk discovery by accessing such services. The transsexual may have never met another transsexual; there may literally be nowhere to turn.

Despite all this, it is possible for a transsexual to behave in a responsible manner. It can require some things: an acceptance of self, a realistic appraisal of the demands on the male and female selves, and budgeting of extra time, when needed, to allow costume changes.

The transsexual should strive to behave in a civilized and considerate manner. She should show up on time for appointments (and call when it’s necessary to cancel or reschedule), cancel only in absolute emergencies, follow through on promises (and not make any promises which are difficult to keep), show consideration for and politeness toward others, dress appropriately for the situation, return phone calls, leave messages on answering machines (and not just hang up), pay debts promptly or make arrangements for a payment plan), and in general, behave with decorum. All these are skills which any individual can acquire, and are easily transferable from the masculine self to the feminine.

Some individuals, of course, do not have such skills (even in their male lives), and are not interested in acquiring them. That is a lifestyle choice, and an unfortunate one, as it makes life difficult for others, and ultimately makes life difficult for the individual. Others just can’t seem to transfer those skills, and while being consummately dependable as a man, may be flighty, unpredictable, or erratic as a woman. If such differences persist across time, such persons should take a serious look at their notions of what men and women are like, and ask themselves if they are retreating into feminine behavior as an escape from their idea of what it is like to be a man.

Publications of the transgender community can help by bringing to light such issues, forcing the gender community to take a critical look at itself. Outreach by gender centers and support groups can educate professionals and others, alerting them to the special problems transsexuals have. But the burden is on the transsexual herself; only when she gets her act together will she become part of the solution and not part of the problem.

After six months or working with Alice, Margie discovered that Alice had not always been a woman. “I can’t believe she’s had a sex change!” she told her husband that night. “She’s just the nicest person! She’s so ordinary. Just like everyone else. I really like her. I do. You know,” she said, “she’s made me realize transsexuals are just like everyone else.”

From the Director's Desk (Text)

Copyright 1990, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Denny, D. (1990, Spring). From the director’s desk. Insight, 6(1), p. 1.

Despite its name, the Montgomery Medical and Psychological Institute was a support group. This is my note as one of the editor’s of insight and newly-appointed director of MMP&I.

From the Director’s Desk

by Dallas Denny

We are grieved to report the death of Janice, a long-time member of the support group, and of Richard, the life-partner of Lauren, both ex-group members. Both Jan and Richard were wonderful people, and we are diminished by their passing.

Are transsexuals reliable? That is the them of this issue of Insight. The question might as well be “Are relatives reliable?” or “Are politicians honest?” The answers, of course, are yes and no. We took a critical yet (we hope) kind look at our paraculture, and frankly, while we found much of which to be proud, there is room for improvement. We hope our readers will engage in a moment of honest self-examination and ask themselves if they are part of the solution or part of the problem.

The phone at the Montgomery house is an active puppy, ringing at all hours of the day and night, bearing tidings, good and bad, or bringing us a friend who wants to chat. most people exhibit good telephone manners, and, considering that the phone is busier than that of many small businesses, such consideration makes life easier. To those who are brave enough to talk to the answering machine, who leave messages and numbers so I can return calls, who wait until mid-morning to call on Saturday or Sunday, and who don’t call after midnight, I say “Thank you.” To the rest of you, I suggest this: read this issue of Insight from cover to cover.

A word on protocol: my job is to manage the affairs of the Institute and to provide services for its clients. In this responsibility I am greatly aided by the experience and knowledge of Jerry and Lynn Montgomery, who after years of service have expressed a desire for a little rest. I consult with them daily, and already they have helped me to grow in this important job. They request that all correspondence and phone calls be directed to me. I will relay your messages to them, and I will defer to them when needed. By taking your difficulties directly to them without giving me a chance to help, you are compounding a problem. Please ask for me when you call. Chances are I can be of assistance. If not, I’ll met with Lynn and Jerry and get back to you.

To help in the transition of leadership (and to give Lynn and Jerry their phone back), we have two new phone lines. MM&PI has its own number, and I have had a personal line installed. Lynn and Jerry are asking that group members no longer call them at their home, but to instead use the MM&PI line (when a personal response is not needed), or to phone me at my new number. Jerry and Lynn are friends of many group members, but in the interest of fairness are not making exceptions. Please help us alleviate the phone crunch. Everyone.

In looking over what I’ve just written, I’m afraid it may seem excessively negative to the reader. I don’t mean to be negative (although what must be said must be said). I’m very happy with our group, and with its members. Joining the group was the best thing I ever did, and being its director is one of the most challenging tasks I have ever undertaken. I can’t begin to express how grateful I am to even know the group members. Before February, 1989 I had never met another transsexual! And the problems we have are growing pains—the best kind to have.

See you next issue.

Survey

This article was published with a questionnaire that was distributed by the Montgomery Institute. I’m not sure how widely, or if the results were ever analyzed.