Preschool Children’s Performance on Two Measures of Emotional Expressiveness Compared to Teacher Ratings (1982)

©1982, 2013 by Dallas Denny, Lynneda J. Denny, James O. Rust, and Taylor & Francis, Inc.

Source: Dallas Denny, Lynneda J. Denny, & James O. Rust. (1982). Preschool children’s performance on two measures of emotional expressiveness compared to teacher ratings. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 140, pp. 149-150.

Photo: Composite of six photographs used by Dr. Carroll Izard in his studies of human facial expression.

This paper was based on Lynneda Denny’s master’s thesis. Lynne and I were once married.

Journal of Genetic Psychology Pages (PDF)

Preschool Children's Performance on Two Measures of Emotional Rating, Original Version (PDF)

Preschool Children’s Performance on Two Measures

of Emotional Expressiveness Compared to Teacher Rating 1 2

Dallas Denny, Lynneda J. Denny, and James O. Rust

Middle Tennessee State University

1. The study is based on a Masters Thesis by the second author. Reprints are available from J.0. Rust, Box 533, MTSU Station, Murfreesboro, TN 37132

2. Our thanks to Dr. Carroll E. Izard for the use of his materials.

Summary

The present study compares teacher ratings of children’s level of emotional expressiveness with the children’s ability to recognize emotional intent from photographs and their ability to produce facial expressions. Thirty boys and girls ranging in age from 3 to 5 years were shown triads of photographs and asked to select a keyed emotion (recognition task). Later, the same children were videotaped while being asked to produce each of the seven emotions used in the recognition task: joy, fear, disgust, distress, surprise, interest, and anger (production task). Three graduate students were asked to view the videotapes and decide which of 10 possible selections the child was producing, The results indicated increases across age in the children’s ability to produce emotions which the judges correctly identified. There was not a significant relationship between teacher rating and the performance of the children in recognition and production tasks, but teachers tended to rate the older children as less emotionally expressive than the younger children.

Just as it is important to investigate the child’s ability to understand and generate facial expressions representing emotions, it is also important to study teachers’ perceptions of how well children demonstrate this ability in their relationships with peers, relatives, and teachers. Several studies have shown that preschool children are capable of recognizing and producing emotional expressions. Various researchers have used live presentations as well as photographs, films, or videotapes in both recognition and production tasks (l, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8).

Izard (6) did extensive crosscultural analysis of the ability of American and French children to recognize and label emotions. He formed pictorial triads depicting emotional intent from posed photographs of models. Each triad consisted of a keyed emotion photograph and two different randomly selected emotion photographs. A sampling of 286 American children and 140 French children ranging in age from 2 ½ through 9 years was tested on both emotion recognition and emotion labeling tasks. In the emotion recognition task the children were asked to show or point to the picture that depicted the keyed emotional expression. For the emotion labeling task the children were asked to describe or give a term for the emotion represented in the pictures. The score calculated was the number of correct responses or descriptions of the emotion. Results showed a substantial growth curve for age across cultures in both recognition and labeling.

In 1972 Odom and Lemond (8) replicated Izard’s recognition task and added a production task in which 32 kindergarten and 32 fifth-grade children participated. The production task required the children to put their heads into a Masonite frame and look toward a movie camera. Each child was asked to do either an imitation-production task or a situation-production task. In the imitation-production task the children were shown two pictures and asked to make a face like the person in the picture. For the situation—production task the subjects were told a situation and asked to produce a face like they would if they were in that situation. Trained judges were asked to score the children after watching a frame-by-frame playback for each attempted expression. Results showed a lag between labeling and production for both age groups, with no reduction of lag with increasing age. Fifth-graders did considerably better than kindergarteners on both imitation-production and situation-production tasks and on the labeling task.

The major purpose of the present study was to compare the performance of children on emotion recognition and production tasks to teachers’ judgements of the emotional expressiveness (the ability to understand and generate facial expressions) of those children. It was hypothesized that there would be a positive relationship between age of the children and scores on both recognition and production tasks. A positive and significant relationship was predicted between teacher ratings and the children’s ability to recognize and produce emotions by means of facial expressions.

Method

Subjects: Subjects were 30 preschool children who attended nursery schools in Tennessee. All were representative of the middle socioeconomic class, and all were estimated by their teachers to have about average intelligence. Ten of the children were 3 years of age, 10 were 4 years of age, and the remaining 10 were 5 years of age. Age was considered to be the independent variable. Sex, race, and intelligence were not systematically investigated.

Judges: Three volunteer graduate students of Middle Tennessee State University were asked to evaluate responses of subjects completing a production task.

Apparatus and Materials: Pictorial triads used by Izard (6) in a cross-cultural study were used for an emotion recognition task. Each picture triad consisted of three 3 x 5 inch black-and-white photographs pasted on a cardboard base. In each triad there was one keyed emotion photograph and two randomly selected emotion photographs. There were four triads keyed for each emotion. Seven emotions were used, resulting in a total of 28 triads. Order of presentation of the triads was predetermined by Izard.

Teachers of the subjects were given a rating sheet consisting of five questions regarding the children’s degree of emotional expressiveness with peers, relatives, and teachers. They were asked to rate each question using a ten-point scale. Questions were as follows: 1) Is the child sympathetic toward other children? 2) Does he emotionally express himself with children as well as adults regardless of who or how many observers are present? 3) Does he express facially his emotions using a variety (three distinct emotions or more) of emotions to transmit his feelings? 4) Is he influential in the way he expresses emotions? 5) Is he influenced by the facial expressions used by others (either parents, peers, or any other person with whom he may interact)?

A black-and-white videotape machine was used for taping of a production task.

Procedure: Teacher rating sheets were distributed at least one day prior to testing. The ratings were made and the sheets returned to the experimenters before the subjects were tested.

Two measures similar to Odom and Lemond’s recognition and production tasks were given. These were also called recognition and production tasks, and were considered to be indicators of emotional expressiveness.

Seven of Izard’s nine emotions were used for this younger sample: joy, fear, disgust, distress, surprise, interest, and anger. The emotion recognition task was given first. Each triad was held in front of the subject by an experimenter as the appropriate request was made. Requests followed the stem, “Show me the one who is …” or “Can you tell me (point to) the one who is ….” If a child seemed unable to recognize the name of the emotion, he or she was not given a descriptive phrase. A tally was made of the subjects’ correct responses.

The production task followed the recognition task by 5 minutes. For the production task, each subject was given two chances, each of which lasted approximately 10 seconds, to present a requested facial expression. All seven emotions were asked randomly of the subjects. The request for the child to produce the expression began, “Can you make a face like you …” or “How would you look if you ….” This was followed by the same emotion terms and/or phrases used in the recognition task.

Before scoring the production task, the judges were shown a pilot videotape showing one 3-year-old, one 4-year-old, and one 5-year-old completing the production task. These three children were volunteers who did not participate in the recognition task. The videotaped pilot was used to acquaint the judges with their task and to give them a sample of the responses of the subjects of each age group. After viewing the videotape, judges were told which expression the children were attempting to convey. Examples of the photographs used both in this study and by Izard were also shown to the judges. This was followed by a discussion period. The judges seemed to be well acquainted with their task after this discussion period and performed their tasks separately and without any assistance afterwards.

Judges were asked to view videotapes of the production task and to assign emotions to each attempt by the subjects to produce an expression. The judges were given 10 choices of emotional classifications; the seven emotions actually used in the production task plus shame, contempt, and undetermined. The three extra classifications were given to the judges so they could not assign emotions to the subjects by elimination. Judges were instructed to use the classification “undetermined” only if no expression was discernable. They were also told to write which emotion they felt the subjects were producing, even if it meant using the same emotion more than once.

Judges were asked to view both attempts by the subjects before making their decisions. An interval of 10 seconds was given after each pair of attempts to allow the judges to write their decisions.

Results

For each child a score was calculated for 2) teacher rating, 2) emotional recognition, and 3) emotion production. The teacher rating was obtained by adding scores of the 5-item 10-point scale. The teacher rating scores ranged from 19 to 45 on a 50-point scale; the higher the score, the higher the rating of the child’s emotional expressiveness.

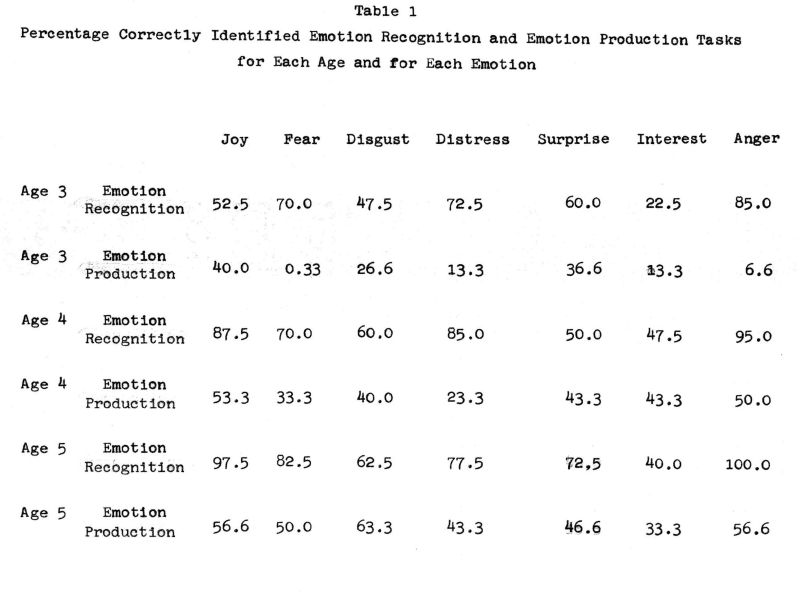

Emotion recognition was calculated from four trials per emotion for each of seven keyed emotions. Thus the highest possible score was four for each of seven emotions or a total score of 28. Scores on emotion production were calculated by adding the responses made by the three judges. Each child attempted to produce a recognizable facial expression for each of seven emotions. A child’s production score was determined by adding those attempts which were correctly identified. The highest score a child could obtain was three for each of seven emotions or a total score of 21. A score of three indicated that all three judges had correctly identified the expression produced. Table 1 lists the percentage of correctly identified emotion recognitions and productions by age and emotion.

Chi square tests on the frequency of correctly judged emotion productions indicated that each judge identified the attempted facial expression correctly at levels far exceeding chance (p<.0l). Additional chi square tests showed that there was an overall increase in judged correct responses across ages 3, 4,and 5 years, and between ages 3 and 4 years and ages 4 and 5 years (p<.01). Overall agreement between judges for each produced emotion (whether correctly or incorrectly identified) was .40.

Seventeen 3 x 1 unweighted means analyses of variance were performed on each of the following dependent variables: teacher rating; recognition of joy, fear, disgust, distress, surprise, interest, anger, and total emotions; production of joy, fear, disgust, distress, surprise, interest, anger, and total emotions. The independent variable was age (3, 4, and 5 years at last birthday).

Teacher ratings were found to be significantly different for 3-, 4-, and 5-year olds (p< .05). Additionally, significant age main effects were found for each of the following variables: recognition of joy, p<.01; recognition of total emotions, p<.05; production of fear, p<.05; production of anger, p< .01; and production of total emotions, p< .01.

The Tukey test for highly significant differences was calculated between ages 3 vs. 4 years; 4 vs. 5 years, and 3 vs. 5 years for each of the 17 analyses of variance; thus, 51 calculations were made. Between ages 3 and 5 the Tukey tests reached significance for the emotion fear for both recognition (p<.05) and production (p <.05) tasks. Results were also significant between ages 3 and 5 for total emotions for both recognition (p<.05) and production (p<.ol) tasks. Between ages 3 and 4, results were significant for total emotions for the production task p<.05).

Pearson Product-Moment correlations were calculated for all 18 variables, Age and teacher rating were found to be significantly negatively correlated (p<.05). For the recognition task, performance on the emotions joy and anger, as well as performance over all seven emotions, was positively correlated with age. For the production task the number judged correct for the emotions fear, disgust, distress, and anger, as well as total judged correct responses over all seven emotions, were also positively correlated with age. Teacher rating was found not to be correlated with performance for any single emotion or over all emotions for the recognition task, or for number of judged correct responses for any single emotion or total judged correct responses for the production task.

Discussion

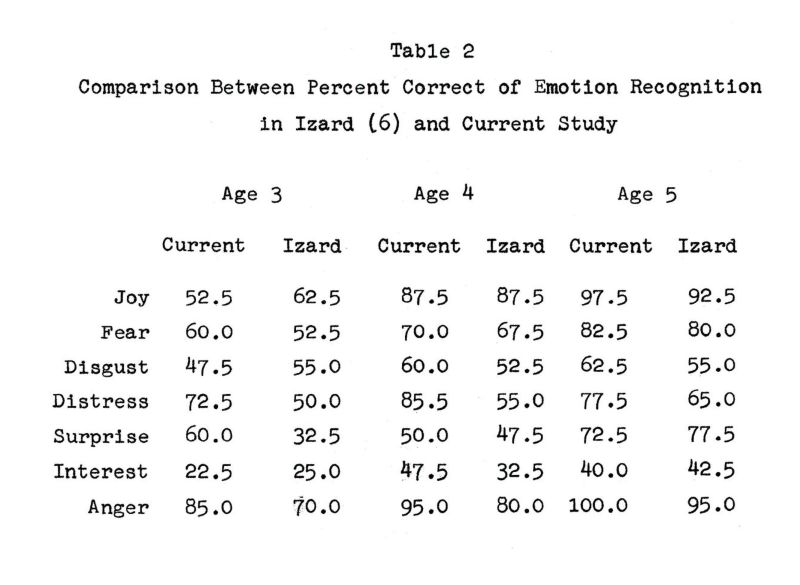

The results reflected increases across the ages of the children, both in their ability to recognize emotions and in the ability of judges to correctly determine produced expressions (Table 1). These findings are consistent with previous studies. Izard’s findings for 3-, 4-, and 5-year olds are remarkably similar to the findings of the present study in the increases in the ability to recognize the emotions joy, fear, disgust, distress, surprise, interest, and anger from photographs (Table 2).

Borke (1) found that the ability of Chinese and American children to recognize social interaction situations representing the four emotions happy, afraid, sad, and angry increased by as much as 90 percent between the ages of 3 and 6 years. Gates (3) found a gradual increase in the ability of children between the ages of 3 and 14 years to recognize from posed photographs the emotions joy (laughter), fear, distress (pain), surprise, anger, and scorn.

Odom and Lemond (8) found that fifth-graders were both better recognizers and producers of facial expressions than kindergarten pupils for the emotions joy, fear, disgust, distress, surprise, interest, and anger. The kindergarten children showed a significant difference (p<.01) between abilities to discriminate and produce facial expressions for all emotions except interest and joy. A study by Hamilton (5) had similar findings. (6)

In the present study, one emotion, anger, was correctly determined by almost all of the 4-and 5-year-olds. This indicates that 4- and 5-year-olds have learned to recognize this emotion and discriminate it from other emotions. However, among the 3-year-olds, anger was the least successfully produced of the seven emotions; there was a substantial increase in successful production between 3 and 4 years of age. This may be an instance of developmental lag between perception and production of facial expressions, since 3-year-olds did quite well in recognizing anger. Odom and Lemond noted that this lag had been identified with regard to discrimination and drawing of shape configurations and with regard to understanding and vocal production of language. They demonstrated that this lag exists also for facial expressions. Similarly, there were rather large increases in recognition of interest and joy between ages 3 and 4, indicating that perhaps the children were actively learning to recognize these emotions. Again, there was some indication of developmental lag (Table 1). These data indicate that some of the emotions used in this study were too difficult for even 5-year-olds to recognize consistently (e.g. interest).

Teachers tended to rate older children as less emotionally expressive than younger children. This may be due to a tendency of children to repress facial expressions of their emotions as maturation occurs. Izard has noted that socialization training may inhibit the production of facial expressions. The term “display rules” has been introduced by Ekman and Friesen (2) “to describe what people learn about the need to manage the appearance of particular emotions in particular situations”(p. 137). For instance, a 3-year-old might be quite uninhibited about crying when his feelings are hurt, while a 5-year-old might “act grownup” and suppress the tears. There is evidence that particular emphasis is placed on learning to control facial expressions, to the extent that the body may provide better cues than the face as to whether a person is being deceitful, at least in adults (7).

However, scores on the teacher rating sheet were not correlated with emotional expressiveness. It may be that the scale was insensitive to emotional expressiveness, or that the teacher’s were not skilled at judging expressiveness. It should be noted that the teachers were not questioned about the specific emotions which the children were asked to recognize and produce, but rather about the general level of expressiveness of each child. Izard’s Teacher Rating of Social Adjustment Scale showed a significant relationship to the emotion labeling task (p <.01) but not to the emotion recognition task presented in his study.

The hypothesis that a positive relationship would exist between teacher ratings and the children’s ability to recognize and produce emotions by means of facial expressions was not substantiated for either of the measures given. Teacher ratings were negatively correlated with the age of the children, indicating that “display rules” may cause children to become less emotionally expressive as they mature. The hypothesis that there would be a positive relationship between age and scores on each of the measures given was verified. Findings were consistent with previous studies.

References

I. Borke, H. The development of empathy in Chinese and American children between three and six years of age: A cross-culture study. Developmental Psychology, 1973, 9, 102-108.

2. Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. Unmasking the face. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1975.

3. Gates, G.S. An experimental study of the growth of social perception. Journal of Educational Psychology, 1923, 14,

449-462.

4. Hamilton, M. L. Imitation of facial expressions of emotion. Journal of Psychology, 1972, 80, 345-350.

5. Hamilton, M. L. Imitative behavior and expressive ability in facial expressions of emotion. Developmental Psychology, 1973, 8, 138.

6. Izard, C. E. The face of emotion.New York: Appleton Century-Crofts, 1971.

7. Littlepage, G., & Pineault, T. Verbal, facial, and paralinguistic cues to the detection of truth and lying. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1978, 4,

461-464.

8. Odom, R.D., & Lemond, C.M. Developmental differences in the perception and production of facial expressions. Child Development, 1972, 43, 359-369.