Electrolysis in Transsexual Women: A Retrospective Look at Frequency of Treatment in Four Cases (1997)

©1997, 2013 by Dallas Denny & Ahoova Mischael

Source: Dallas Denny & Ahoova Mischael. (1998). Electrolysis in transsexual women: A retrospective look at frequency of treatment in four cases. In D. Denny (Ed.), Current concepts in transgender identity, 1998, 335-352 and Journal of Electrolysis, 1997, V. 12, No. 2, pp. 2-16.

This study is, so far as I am aware, the only empirical study of electrolysis in transsexuals.

Journal of Electrology Pages (PDF)

Chapter 20

Electrolysis in Transsexual Women

A Retrospective Look at Frequency of Treatment in Four Cases

By Dallas Denny and Ahoova Mishael

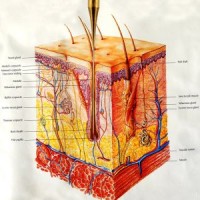

The role of the electrologist is, of course, to permanently remove unwanted hair from the face and body. Many electrologists treat only females, but males frequently seek treatment as well. Men may desire to be rid of hair for any number of reasons: because they dislike shaving or have sensitive skin which makes shaving painful or difficult, because they are bothered by ingrown hairs, because they wish to have an even beard or hair line, because hair grows in unwanted areas like the back, or more thickly than wanted, or simply because hair on certain parts of their bodies just does not fit their self-image. Into the latter category fall males with transgender feelings—men who wish to become women, or more like women. [See Note 1]

Transgendered people are of both sexes, but the electrology needs of the genetic female who is moving in the masculine direction are quite limited, whereas the post-pubertal genetic male will almost always need extensive facial electrolysis in order to achieve a suitably feminine appearance. In the remainder of this paper, we will use the words transsexual woman to refer to the male who is becoming or who has become a woman. We will address the special needs of the female-to-male transsexual (transsexual men) and the male crossdresser in the discussion section.

Electrolysis Needs of Transsexual Women

Despite an internal identity as females, transsexual women, before transition, find themselves with unremarkably male bodies. This means that in the absence of intervention with opposite-sex hormones, their facial, body, and head hair will follow the normal male pattern, with a diamond-shaped public patch which extends upward towards the navel, increased axillary hair, a heavy growth of facial hair, and thick dark hairs on the arms, legs, and torso (Dupertuis, Atkinson, & Elftman, 1945; Montagna, 1976).

Baldness, heavy body hair, and beard growth can be very ego-dystonic in transsexual women, who desire to pass in society as nontranssexual (Finifter, 1969) [But see again note 1]. Bringing body and facial hair under control is critically important for the individual who plans to live as a woman, for the male beard can be concealed only by ingenuity and hard work, and even then not with complete success. [2] The transsexual client will in fact have the same distress about facial hair as the genetic female with hirsutism, especially if living as a woman.

Hormonal therapy, which is an essential part of the process of sex reassignment, will generally cause body hair patterns to change in the female direction (especially when antiandrogens are used; see Prior, Vigna, & Watson, 1989), but depending on the level of hirsutism of the individual, electrolysis on the torso, neck, legs, and arms may be necessary. With estrogen and progesterone, facial hair growth will slow, and with anti-androgens such as spironolactone, there may actually be some thinning of facial hair (Prior, Vigna, & Watson, 1989; Basson & Prior, in this volume), but unless the masculinization process is arrested early in puberty (which rarely occurs) or the individual naturally has sparse beard growth, extensive facial electrolysis is usually necessary (Finifter, 1969).

Sex reassignment is a process of physical and social change that takes place over a number of years, culminating, in some cases, in genital surgery, which is a confirmation of the new gender, rather than the cause of it (Laub, Laub, & Biber, 1988). Living and working in the new gender role is in fact a prior requirement for surgery, as outlined in the Standards of Care of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, Inc (Walker, et al., 1990), the guidelines which are consensually used by health care professionals. The individual must have proven competence in handling herself in the new gender before irreversible surgery; this is called the real-life test.

As it is very difficult to begin this period of crossliving while there is still heavy facial hair, electrolysis is best done early in the transition phase, while the individual is still living in the male role. Facial hair growth on a man will not ordinarily cause undue comment or ridicule, but the same growth on a woman, transsexual or otherwise, can be highly stigmatizing and very embarrassing. Nonetheless, many transsexual women do not have a significant amount of electrolysis before entering the period of real-life test, or even before surgery. Some never have electrolysis.

The individual in real-life test may have scheduling difficulties caused by the need for seclusion while allowing the hair to grow for a day or two before treatment. A busy schedule may make it difficult to allow the hair to grow to a suitable length for treatment, and the individual may not be willing to show herself in public during the time necessary for growth. [See Note 3] However, by careful juggling of the schedule (e.g. treatment on Saturdays or evenings), it is possible for the transsexual individual to have electrolysis while in real-life test.

Removal of facial hair can require many hours of treatment. Anne Bolin, in her book In Search of Eve (1988), estimates that an average of 200 hours of electrolysis are needed to completely clear the average male face. We have seen similar estimates in the magazines and newsletters of the transgender community. As in all electrolysis, it is critical that the hair root be killed. It is not unusual for a transsexual woman to undergo hundreds of hours of electrolysis with no significant reduction of beard density. Bolin gives an example of an individual who, after more than 300 hours of treatment, was still able to grow a beard. We have known individuals who have said they spent over ten thousand dollars in a fruitless attempt to rid themselves of facial hair.

As the plans for the future of the transsexual woman may depend to a great extent upon having the facial hair under control, it is critical that she find an electrologist who is capable of removing her facial hair with a minimum of treatment, but without causing unsightly scarring, pitting, or discoloration of skin. Because the facial hair of the male is more difficult to remove than the thinner hair of the female, it is important that the transsexual woman seek an electrologist with experience with hair removal in males, and preferably one who has worked extensively with transsexual women. This is not always possible, however, because of geographic limitations.

It is important that electrologists who are treating transsexual women be aware that they may need to modify their techniques somewhat for these clients. Aspen (1995), noted that she has had success with the manual blend method, using dual foot pedals, using as a base rate (which is modified, as needed) a galvanic current ranging from 4 to 7 milliamperes, and high frequency ranging from 1.2 to 2.5 (low intensity). Aspen varies her timing according to the thickness of the hair: “Sometimes 8 seconds or less of dual currents is sufficient, and at other times it is necessary to lead with galvanic, for say 5 seconds, adding high frequency for another 5 seconds. Be consistent with the count… and use larger needles for the beard, whenever possible” (pp. 11, 13).

Some electrologists have reported success with insulated probes; current is delivered only at the tip of the prove. This theoretically causes less damage to the skin, although we are unaware of any data to support this.

A few electrologists advertise marathon electrolysis sessions in the magazines and newsletters of the transgender community; it is not unheard of for an individual to fly or drive to another state and have 40 or more hours of electrolysis in a five or six day period. While this certainly is much less expensive, both travel-wise (fewer trips are necessary) and treatment-wise (there is generally a discount for booking multiple-hour sessions), it seems reasonable to assume that even with an insulated probe, this poses greater risk for damage to the skin than the same amount of treatment stretched over weeks or months.

As we prepare to go to press, there has been a great deal of speculation in the transgender community about electrolysis delivered via laser. Although lasers promise the development of an effective, rapid, and inexpensive way of getting rid of facial hair, we are reminded of the many past methods of electrolysis which were unproven and ultimately abandoned. The individual anxious to transition might well be better served by opting for proven methods than by waiting for technological breakthroughs which might or might not happen.

Thermolysis, galvanic electrolysis, and the blend all have their proponents, both within the transsexual community and within the community of electrologists, and both authors have heard reports of successful and unsuccessful treatment using all of these methods. We believe that the technique (level of expertise) of the electrologist is the most critical factor in clearing the face and other areas of hair, whether in transsexual or nontranssexual women. Unfortunately, it is sometimes difficult for the transsexual woman to judge the efficacy of electrolysis, for with treatment the hair will be removed, even if the root has not been destroyed. What seems to be a successful course of treatment will not be revealed to be unsuccessful until circumstances prevent the individual from seeing the electrologist for several weeks. Suddenly, it may become apparent that there has not been any appreciable reduction in beard growth. It goes without saying that any patient would find this highly distressing.

One way for both the patient and electrologist to monitor the effectiveness of treatment is by the resistance of treated hair to removal with tweezers. After treatment, the hair should slide easily out of the follicle. If there is resistance, in all likelihood, the hair root has not been destoyed, and there will be regrowth.

From conversations with many transsexual women, we have discovered that Bolin’s estimate of 200 hours may be a reasonable estimate of the time required to “clear” a genetic male’s face. The second author, Ahoova Mischel, has practiced electrology for 18 years, and has treated hundreds of transsexual women. Our examination of her treatment data shows that she has been successful in clearing the faces of the majority of her transsexual clients with far fewer hours of treatment, using the thermolysis method. Moveover, many of her clients have made dramatic personal changes as a result of combined electrolysis and hormonal treatment.

While our data are not as rigorous as we would have liked (i.e., we were unable to do actual hair density counts or strictly control for previous electrolysis), our subjective impressions of the individuals before treatment were “Yes, she has a beard within normal male limits,” and afterwards that their facial skin was free of large, thick hairs, as is the case with most genetic females; and that their facial skin did appear much more feminine. Progress of treatment was usually coincident with the beginning of life in the feminine role, and it is our opinion that the electrolysis made a significant contribution to successful full-time crossliving. We believe our data, limited as they are, are the first such ever presented.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were four adult transsexual women retroactively selected as representative from a pool of more than one hundred transsexual women who had seen the second author for treatment. Their ages ranged from the early thirties to the mid-forties. Selection was dependent upon 1) initial presentation with a significant amount of facial hair, which would, in the opinion of both the subject and the second author, were within the normal male range and would have made living as a woman difficult; 2) a stated history of little or no previous electrolysis (10 hours maximum); and 3) regular and continued treatment, until the second author and the subject reached a consensus that continuing electrolysis was not (or was only rarely) needed. We found four subjects who clearly met these criteria. Three had transitioned, and were living as women before the end of treatment. The fourth was living as a woman (with considerable harassment from her co-workers) when she entered treatment.

Treatment

Treatment was by thermolysis, using an Instantron Model SS69 machine. Time and intensity settings were adjusted according to the individual needs of each subject. Subjects were encouraged to come weekly or bi-weekly for treatment, as their finances permitted, but this was not always possible.

All treatment was given by the second author or occasionally by Hanna Dalal, using the same equipment. Typically, she would work in a specific area of the face, and would in subsequent sessions clear that area before moving into untreated areas. Thus, it was not necessary for the subject to shave the treated areas, so long as she was having weekly treatments. [See Note 4]

Usually, treatment would start with the cheek or lower neck area, but the site of initial treatment varied with the wishes of the subject. Subjects were urged not to shave or pluck areas which had been cleared, although they sometimes did, especially when extended times elapsed between treatments.

Results

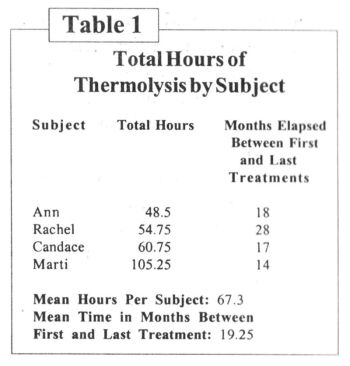

The hours in treatment ranged from 48.5 hours for Ann, whose facial hair was relatively sparse, to 105.25 hours for Marti, who presented with an exceptionally heavy beard. The mean was 67.3 hours. Total hours of thermolysis for each subject are shown in Table 1.

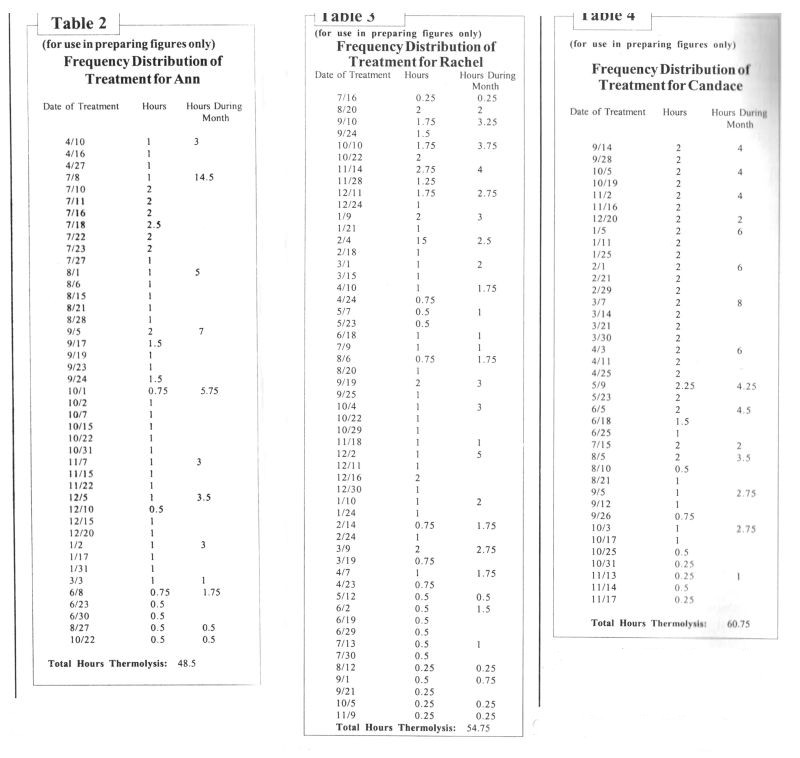

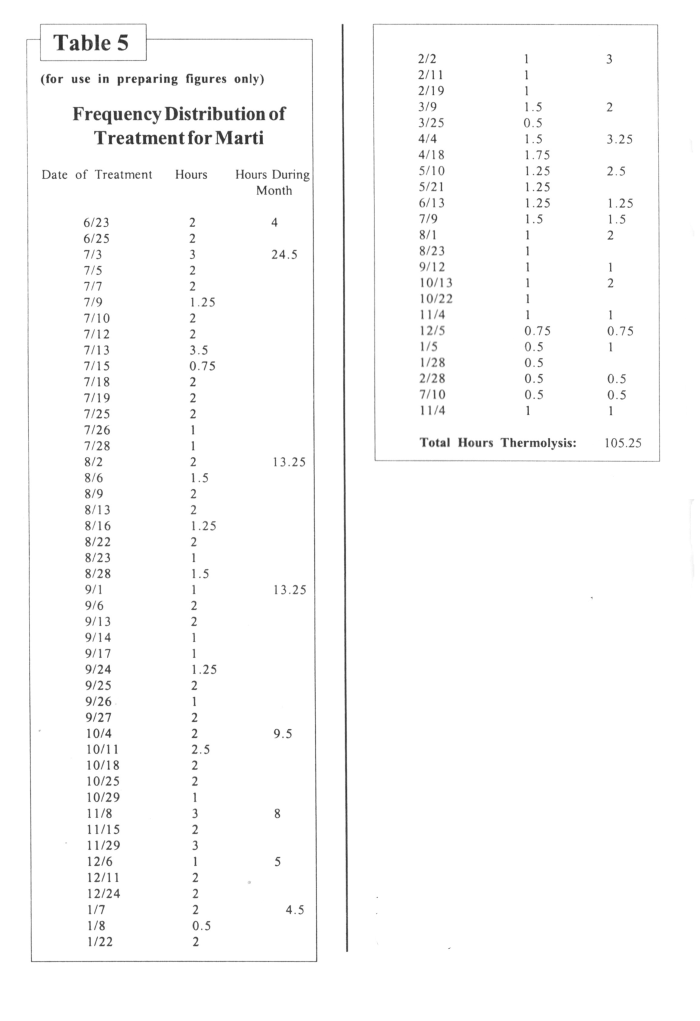

Ann’s 48.5 hours of treatment took place over 18 months. Initially, she came frequently for treatment, and then less often, as regrowth decreased. Table 2 shows a frequency distribution for Ann’s treatment. We noted a similar tendency for the other three subjects (Tables 3-5).

Length of sessions gradually decreased for all four subjects. Early in treatment, most session lengths were one hour or more. Towards the end of treatment, three of the four subjects (Ann, Rachel, and Candace) had mean session length of 30 minutes or less. Marti’s session length increased from thirty minutes to one hour near the end of the treatment period, but she was coming only two or three times a year at that point.

It is worth noting that during her second month in treatment, Marti had 25 hours of thermolysis. This was at her insistence, for she was crossliving full-time and was ordinarily unwilling to grow her facial hair. She was on leave for a number of weeks following surgery (castration), and wanted to have as much electrolysis as was possible before going back to work. The second author had concerns about such an intensive schedule, but as Marti was already living as a woman and was unwilling to begin electrolysis except on her schedule, the second author acceded to her wishes.

Initially, all four subjects had facial hair growth which visually appeared to be within the normal male range. Afterwards, none of them shaved, which allowed for the growth of vellus hairs, giving their facial skin a feminine appearance. There was no visible scarring, pitting, or discoloration from electrolysis.

Subjects have continued to schedule treatment on an intermittent basis, but sessions are typically short, and regrowth sparse.

Discussion

Our experience suggests that if electrolysis is ongoing for more than about 10 hours without significant reduction of beard growth (and specifically, if the length of the session necessary to clear the face or certain sections of it has not become shorter than earlier in treatment), there should, if the individual’s life circumstances permit, be a treatment holiday during which progress is evaluated. If treatment is judged to be ineffective, then a change should be made either in electrologist or in the method of treatment (e.g., blend instead of thermolysis, or a significant change in the intensity and/or duration of the current).

Future research should attempt to establish an objective method of effectiveness of electrolysis (e.g., density counts before and after treatment).

We cannot overemphasize the importance of facial electrolysis in transsexual women. The presence of heavy facial hair requires frequent shaving, with subsequent skin irritation, and no matter how closely the individual shaves, no matter how blonde the facial hair, no matter how much makeup is applied, no matter how much the transsexual woman insists that her beard doesn’t show, the sophisticated observer will make assumptions that what is being covered up on the face relates to what is being covered up by the clothing.

Male crossdressers—that is, men who dress as women, typically take two or more hours to ready themselves for public outings. Most of this time is spent in trying, with varying degrees of success, to control unwanted hair growth. Until her hair growth is brought under control, the transsexual woman must undergo the same sort of rigorous preparation for even the most simple excursion—that, or risk being perceived as a man. Wearing heavy makeup, wigs, and prosthetic devices is more akin to crossdressing than transsexualism, which is a process of becoming, rather than simply dressing up. Control of unwanted hair is an integral part of that becoming. Few women have the luxury of a two-hour grooming process every day, and, if the transsexual woman is successful in her new role, neither will she.

A smooth face is a strong feminine signal, but even more so is a face which has the same amount of vellus hairs as is found in nontranssexual women. A face with these fine, light hairs will provide feminine gender cues which may not be consciously recognized, but which will nevertheless affect the overall perception of the individual. Shaving removes these vellus hairs as well as the thicker beard hairs.

Before treatment, when presenting as female, the four subjects and many other transsexual clients of the second author wore heavy foundation with beard cover, which they said they hated, but which they felt was necessary. Afterwards, they wore little or no foundation, remarking that they didn’t feel the need for it. They were thrilled that they no longer had to shave, as not having to do so reinforced their private views of themselves as women. Several stated that the morning shaving routine had always reminded them of their maleness.

With the loss of the facial hair came changes in hair style, clothing, comportment, and speech patterns, movement into full-time living [except for Marti, who had already (in the view of her support group, prematurely) moved into the female role], change of name, job changes, new relationships, and a gradual move into a new life. All of the subjects have since had genital surgery, although we point out that genital surgery is not necessary in order to lead a successful and productive life in the new gender role.

While electrolysis was certainly not the only factor which facilitated the change of role for these subjects, it was a critical one, for without it, they would have retained the strong secondary sex characteristic of beard growth, which would have strongly proclaimed them to be male and would probably have had a deleterious effect on their ability to find and maintain employment.

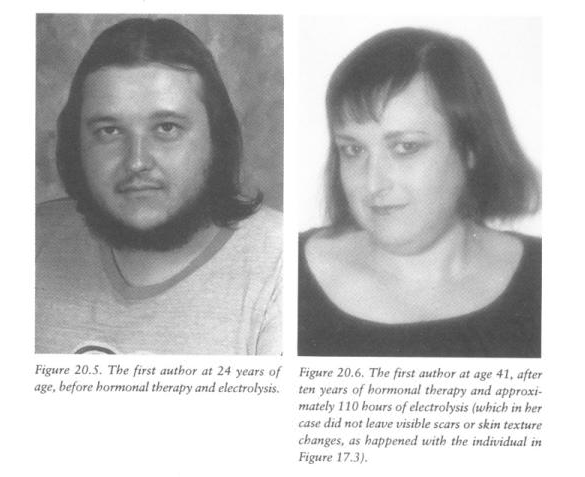

An example of the dramatic difference hormonal therapy and electrolysis can make in a transsexual woman can be seen in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows the first author (who was not one of the four subjects) at 23 years of age, before treatment. Figure 2 shows her at age 41, after ten years of hormonal therapy and approximately 110 hours of electrolysis in 1988-1990. [These figures do not appear in the Journal of Electrology version.]

Male Crossdressers and Female Impersonators

Male crossdressers dress as women for social reasons. Many are heterosexual, some are bisexual, and some are homosexual. Many crossdressers experience sexual arousal from crossdressing in puberty and young adulthood. This may persist, but in many men who crossdress, there comes to be some degree of identification with women, and they develop a desire to look as much like women as possible on those occasions when they do dress (Prince, 1976). Female impersonators, who make their livelihood by dressing as woman, have a similar desire. Some of these men will modify their bodies in an attempt to appear more feminine. Unfortunately, many turn to female hormones which have global effects on body shape, emotional state, and sexuality, rather than to facial electrolysis, which has only local effects and which may actually be more helpful in allowing them to pass as women than a year or two on hormones. However, many crossdressers and female impersonators do approach electrologists for removal of unwanted hair. Total removal of male facial hair via electrolysis may result in a somewhat boyish appearance, but in the absence of other feminization will not have a great effect on the ability of a man to perform as a man, as will happen with a large enough dosage of female hormones taken for a long enough time. Partial removal of facial hair can result in improved appearance as a woman, but allow a convincing stubble when the individual does not shave.

Crossdressers and female impersonators can make good clients, as they often desire not only facial electrolysis, but electrolysis on their bodies as well. It should be noted that for individuals under age 30 not on female hormones, androgens will stimulate new hair growth, requiring on-going electrolysis.

The Transgenderist

The transgenderist falls somewhere between the crossdresser and the transsexual person. By some definitions, the individual who wishes to live full-time in the other gender but does not desire genital surgery is a transgenderist. By others, the transgenderist is an individual who pursues characteristics of both sexes, who walks the middle line of androgyny. In either case, the electrology needs of the male-to-female transgenderist will be similar to that of transsexual women.

Transsexual Men

A significant minority, and perhaps as many as half of all transsexual people are genetic females who wish to live as males. With the introduction of androgens, they will develop facial and body hair which is not distinguishably different from other men. Their electrology needs will for the most part be the same as those for other men, consisting primarily of treatment to reduce pseudofolliculitis barbae, to trim up beard lines, or to remove hair from unwanted areas like the back; however, there is a special consideration regarding phalloplasty.

Phalloplasty, the surgical technique whereby the male sexual organ is created in transsexual men, requires grafting of skin tissue from other areas of the body. This tissue can be taken from the torso, thigh, leg, or inner arm. Because some of this skin may wind up inside the phallus, providing a conduit for urine, it is important that it not be hair-bearing, as calcification tends to occur around hair in the path of the urine (Hage, 1992). Any hair in the donor areas should be removed. Obviously, this will be much easier before the surgery than afterwards.

Because phalloplasty is expensive (transsexual surgeries are almost never covered by medical insurance), and because of aesthetic and functional limitations of this surgery, most transsexual men opt either to forego “bottom surgery,” or to have metadoioplasty (Laub, 1985), a surgical procedure which produces a small phallus from the testosterone-enlarged clitoris. In this case, electrolysis is generally not needed.

Vaginal Hair

In transsexual women, surgeons use penile and/or scrotal tissue and sometimes a flap of skin from the perineal area or a skin graft to line the neovagina. Because this is often hair-bearing tissue, it is important to remove any growth from the areas which will wind up inside the vagina. Otherwise, the vagina can become congested with hair, making dilation (a procedure necessary to keep the vagina open) and sexual intercourse uncomfortable and embarrassing (Farrar, 1993). Removal of these hairs is very difficult (and reportedly, painful) after surgery. Unfortunately, surgeons have been remiss in alerting their patients to the need for this. One surgeon, who we shall not name, remarked in his presentation at the 13th International Symposium on Gender Dysphoria (New York City, October, 1993) that his transsexual patients were so grateful at having surgery that they did not mind having hair in their vaginas. Transsexual women assure us, however, that they do mind (Farrar, 1993).

Because many transsexual women are unaware of the problem of hair-bearing vagina, the American Educational Gender Information Service (AEGIS), released an advisory bulletin in early 1995, designed to educate surgeons, electrologists, and transsexual women about the importance of electrolysis in the pelvic area.

It should be noted that electrolysis in this region is not needed until surgery is on the immediate horizon, by which time most of the facial hair should be removed and the individual should be living and working as a woman. Some individuals will not have hair in the target area, or their hair growth will be so light as to make electrolysis unnecessary. However, because electrolysis is an ongoing procedure, it is important that those with thick hair growth allow sufficient time for clearing the area before the date of surgery. In some cases, this may mean that it is appropriate to start treatment before the advent of full-time crossliving.

The individual who is presenting male with no facial electrolysis of other signs of feminization but insisting on electrolysis in this area should be treated with the same caution as would any male client requesting electrolysis in the genital area. However, the electrologist should keep in mind that many transsexual women do not pass particularly well as women, even after extensive hormonal therapy and electrolysis. Personal knowledge of the individual’s life situation can be helpful to the electrologist in making a decision about treatment in the genital area. If in doubt, the electrologist might ask for a letter or phone call from the individual’s therapist or support group as a confirmation that the request is genuine.

Many transsexual people are ill-at-ease about their condition, and this can cause apprehension in the electrologist. Such clients may schedule appointments and not show, or, more commonly, may dissemble about their real reasons for having electrolysis. The electrologist may be able to ease the client’s apprehension by flatly stating that she treats a number of transsexual clients. This is generally more effective than revealing this information via hints.

The transsexual client may present for treatment looking like any other woman, or looking like an ill-at-ease man in women’s clothing, or in male clothing, looking indistinguishable from other men. The electrologist should remember that the distinguishing characteristic in male-to-female transsexualism is not the individual’s ability to pass convincingly as a woman, but rather her private view of herself as a woman.

While this study is flawed by lack of objective measurement of hair density in the treated areas, by the fact that some of the subjects had had previous electrolysis, and by our retroactive selection of test subjects, we are happy to present these data. Hopefully, future studies will provide better subject selection and more objective measures of the effectiveness of electrolysis.

Notes

[1] Many individuals wish to live as members of the sex other than that assigned at birth, but without genital surgery. The lack of a desire to modify the genitals should not be taken as a counterindication for electrolysis or other body-modifying procedures. Nor should an identity not as a woman or man, but as both, or neither, or as a blend of the two be seen as a counterindication for treatment. Also, some individuals have little or no desire to “pass” in society as members of the biological other sex, even though they live their lives in the clothing of that sex.

[2] The lack of the thin, light vellus hairs which women have on their faces and other subtle cues will alert the sophisticated observer.

[3] The differential in salaries between males and females can make it difficult for the transsexual woman to afford electrolysis in the new role. Discrimination frequently forces talented and qualified individuals out of their pre-transition careers, and makes it difficult for them to find new jobs. The individual whose facial hair or other characteristics makes it difficult to “pass” frequently faces even more discrimination than those who do “pass.” Finding themselves unable to get any job whatsoever and unable to afford electrolysis, even talented and well-educated individuals sometimes find themselves in a downward financial spiral which leaves only sex work as an alternative to homelessness.

[4] Aspen (1995) recommends working on the entire face of transsexual clients, clearing beard growth gradually, so that it is not apparent to observers who see hairless patches that the client is having electrolysis. If cost and speed are not a factor, or if security is an issue, this is certainly advisable. However, it is our experience that the kill rate for hairs in the anagen (early growth) phase is markedly higher than for older, more established hairs. The second author’s clients are often anxious to be rid of facial hair as rapidly as possible, and have been able to explain the cleared areas without undue difficulty.

Summary

The condition called transsexualism is characterized by the persistent desire to change the primary and secondary sex characteristics to resemble those of the other sex. In sex reassignment, the individual actually does this via a series of procedures which may include electrolysis, hormonal therapy, plastic surgery, voice training, and resocialization. In post-pubertal males, facial hair must be removed to facilitate successfully passing as female. This requires the transsexual woman to seek an electrologist. We present data from four male-to-female transsexual subjects, showing the number of hours of treatment across time. Time spent in treatment ranged from 48.5 hours to 105.25 hours (Mean = 67.3 hours, and the time between first and last treatments ranged from 14 to 28 months (Mean = 19.25 months). Our results suggest that when electrolysis is ongoing for more than 20 hours without significant reduction of the time necessary to clear the face, there should, if the individual’s life circumstances permit, be a two to three month treatment holiday during which progress is evaluated. If treatment is judged to be ineffective, then a change should be made either in electrologist or in the method of treatment. We were unable to obtain an objective measure of hair growth from our clients (e.g. beard density count). Future studies should include objective measures of effectiveness of electrolysis.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd. ed., revised. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Aspen, B. (1995, February). Electrolysis for transgendered clients. International Hair Route, 11, 13, 46.

Bolin, A. (1988). In search of Eve: Transsexual rites of passage. South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, Inc.

Dupertuis, C.W., Atkinson, W.B., & Elftman, H. (1945). Sex differences in pubic hair distribution. Human Biology, 17, 137-142.

Farrar, J. (1994). Letter to the editor. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(7), 7.

Finifter, M.B. (1969). Facial hair: Permanent epilation with respect to the male transsexual. In R. Green & J. Money (Eds.), Transsexualism and sex reassignment, pp. 309-312. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hage, J.J. (1992). From peniplastica totalis to reassignment surgery of the external genitalia in female-to-male transsexuals. Amsterdam: Vrieji Universiteit Press.

Laub, D.R. (1985). Metadoioplasty for female-to-male gender dysphorics. Paper presented at the 9th International Symposium on Gender Dysphoria, Minneapolis, MN, September, 1985.

Laub, D.R., Laub, D.R., II, & Biber, S. (1988). Vaginoplasty for gender confirmation. Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 15(3), 463-470.

Montagna, W. (1976). General review of the anatomy, growth, and development of hair in Man. In K. Toda, Y. Ishibashi, Y. Hori, & F. Morikawa (Eds.), Biology and diseases of the hair. Baltimore: University Park Press.

Prince, V. (1976). Understanding crossdressing. Los Angeles: Chevalier Publications.

Prior, J.C., Vigna, Y.M., & Watson, D. (1989). Spironolactone with physiological female steroids for presurgical therapy of male-to-female transsexualism. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 18(1), 49-57.

Walker, P.A., Berger, J.C., Green, R., Laub, D.R., Reynolds, C.L., & Wollman, L. (1990). Standards of care: The hormonal and surgical sex reassignment of gender dysphoric persons. (1990 Revision). Available from AEGIS, P.O. Box 33724, Decatur, GA 30033.