A Tale from Whitey’s Tavern (1967)

©1967, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (1967). A tale from Whitey’s Tavern. Unpublished short story.

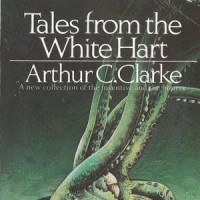

I wrote this story, as best I can remember, my senior year in high school. I had heard of but not read Arthur C. Clarke’s Tales From the White Hart, and the concept of fanciful stories told by regulars at a neighborhood bar intrigued me—and, apparently, Spider Robinson.

A Tale From Whitey’s Tavern

By Dallas Denny

When Whitey came back to the bar that night to get his overcoat, I was sitting at the counter finishing a gin and tonic. When I heard the door open I dove for the open hatch of the tunnel, but I wasn’t nearly quick enough; he had already seen me, and the hatch was in plain view. “Halt!” he cried, and I did, for I knew as well as Whitey that he carries a Model 10 Smith & Wesson in a shoulder holster. “Turn around slow, Buster, and start explaining.”

I turned, but I didn’t get a chance to explain, for Whitey recognized me. He looked as if had seen a ghost, and in a way I guess he had. He forgot all about the pistol in his hand. “My God! It’s Jerry Weston!” he exclaimed, with a look you wouldn’t believe on his unhandsome face. “You’re dead.”

“Not dead, Whitey. Just, you might say… deceased.”

“But five years, man. Five years! Where have you been?” A look of suspicion crossed his face as he found he was still holding his .38. “And what are you doing here? I think I’d better call the police.”

“I’ve quite a story to tell you if you won’t.” Living a monotonous existence for almost two years (Whitey was exaggerating) can make a man do strange things. I told Whitey the truth.

You see, I’m an architect. Used to be, actually. When my pal Whitey Carnes wanted me to design his new tavern, I just naturally felt at liberty to improvise something just for the hell of it. So I took the contractor aside, showed him a different set of blueprints than I had shown Whitey, and made him promise not to breathe a word of it to Whitey. I

hate to say whether money changed hands—but it did. I planned to surprise Whitey on New Year’s Eve, but for reasons I’ll explain in a minute, I never got around to it.

You see, what I had built was a special room between the main room of the bar and the room where Whitey keeps his liquor. It wasn’t much of a place, about seven feet square, but it had a tunnel leading to a spot in the wall just beside the mirror which was behind the bar, and another which opened to the outside. The room was heavily soundproofed. I figured that after I showed it to Whitey we would sit in there and laugh at the customers through the one-way mirror.

I spent quite a lot of time at the bar after it opened. I was one of those fellows who can somehow reach maturity without having his first drink; I had my first in that bar. I must have liked it, because I really began sopping it up. After a two-week drunk I sobered up to find my business was in ruins. My fiancee had left in tears and my checking account was seriously overdrawn.

I tried to salvage what was left, the strain of which led to more drinking. Things got a lot worse. I lost my house and my car—my house was repossessed and I did a pretty good job of destroying a telephone pole with my car. The police were looking for me with a hatful of bad checks I had no hope of being able to pay. Creditors had passed the being-polite stage and several of my clients had filed lawsuits because I hadn’t finished the plans for their buildings after accepting and spending substantial down payments. In short, I was up the proverbial creek.

And then, one night, after I had gotten particularly drunk, I woke up in the dark. You can guess where I was. Right. In the secret room, almost sober and with a terrible taste in my mouth. I must have climbed in from the outside entrance. I crawled out into the tavern, only to find the place closed. Then the idea hit me.

I went to my flat and wrote a note which said in effect, “Goodbye, cruel world,” packed what few belongings I hadn’t hooked into a cardboard box, and carried them to the tavern. I then went to an all-night drugstore and bought an assortment of junk food and bottles of water and paperback novels and a transistor radio with an earplug. Back at Whitey’s I grabbed a couple of bottles and climbed into the room.

After about a month I took the television set which stayed over the bar. Whitey, I guess, chalked the loss up to petty theft. I don’t know if he noticed his minor liquor losses, or the change which periodically disappeared from the cash register.

After Whitey would lock up and go home, I would leave and buy a cheeseburger at an all-night cafe, or cook over a Sterno stove back at the tavern. When my clothes became too offensive I would pick up a pair of pants and a shirt for free at the Salvation Army. I would wash my body and sometimes my clothes in the sink of the bathroom of the tavern, being sure to clean up my mess. I was sneaky about leaving things so it looked like they hadn’t been bothered.

I didn’t get roaring drunk a lot, but I stayed pleasantly stoned most of the time, lying in my room or sitting outside the blood bank with the usual assortment of winos, who couldn’t figure out where I slept or how I managed to always have a bottle. And the weeks turned into months and the months into years. I was happy. I didn’t give a damn what day of the week or month it was or who was President or who terrorist groups were terrorizing.

I had been sitting in the bar, not knowing or

caring about anything when Whitey came in to get his overcoat. I was caught, and like a damned fool I told Whitey the truth.

Whitey didn’t shoot me, but I think he was tempted. He told me the cops couldn’t figure why I had taken so many things if I was going to kill myself. They would have been suspicious if they had found out about those paperback books. But when an unidentified man who matched my description had run under a steamroller, all suspicions were dropped.

Whitey said he sometimes heard noises coming from the wall, but he had thought they came from the police holding station next door. He was starting to tell me how one time he had—but I guess my picking up the gin and tonic was just too much for Whitey—when I woke up, I was in this cell.

I went to court and was sentenced to spend nine months here. I escaped the road gang only because I was in such rotten physical shape. This cell is roomy after a seven-by-seven room. It’s funny I should end up right next door to Whitey’s.

I’m telling you this because you look like a man who can use a drink as much as the next guy. You’re going to be here for a long time, and I’ll need your cooperation. I need a drink. I’m used to it, and I don’t think I’ll make it much longer without one. The tunnel is already started, and there are a few more architectural quirks Whitey hasn’t found out about yet.