Nobody’s Transvestite Fantasy (1999)

©1999, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (1999, October). Nobody’s transvestite fantasy. TG Forum.

This article was written for Changing Men magazine, which abruptly folded just as it was due to be published. It was touch and go whether there would be a final issue, but it eventually proved to be stillborn. And so Nobody’s Transvestite Fantasy was published for the first time on TG Forum.

Nobody’s Transvestite Fantasy

By Dallas Denny

Before I embarked on my transsexual journey, I was not, as psychoanalyst Robert Stoller was known to characterize male-to-female transsexuals, “among the most feminine of men.” Nor was I “among the most masculine of men.” No, I was just ordinary-masculine. Lynne, my wife, accused me of acting a bit light in the loafers on occasion, but she assured me it was nothing to worry about. It was just an occasional limpness of the wrist or other minor slip of my masculine facade.

I looked maybe a little like John Belushi; in fact, I once won a bottle of champagne at a Halloween party for stalking about all night in a bathrobe, doing Belushi’s samurai from Saturday Night Live. I never broke character. When I won a bottle of champagne for best costume, I looked at the proffered bottle of champagne and grasped the hilt of my sword and lifted an eyebrow, and everybody stepped back to give me room.

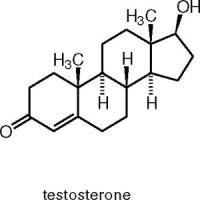

I was a gentle man, a loving man, but testosterone can do strange things; occasionally, I would give in to it. Picture this: I’m maybe 24 years old. I’m in grad school and penniless and my 1963 Fiat convertible has broken. I’m lying underneath it in the dark, the transmission balanced on my chest, trying to get it past the rack-and-pinion steering so it will mate with the engine. It’s not working. I’m filthy from head to foot: leaves are in my hair and in my beard, my hands and arms and face are black with grease. I wrestled with this project all day yesterday, and I’ve been at it twelve hours already today. I lift the transmission until my muscles rebel, and then, sometimes not that gently, set it on my chest, lower it to the ground, squirm out from under the car, turn the steering wheel a bit, prod the malfunctioning drop light with my foot to get it working again, and crawl back under the car. My arms ache. My eyes burn from stuff falling in them. Sharp rocks gouge my back. I hate what I’m doing: hate being dirty, hate the pains in my arms, hate the transmission I’m hugging, the car I’m putting it into, and the world in general. After two days, I’ve worked myself in a pretty damn foul mood.

Inside my trailer home is John, an art fag [1] type Lynne, my wife, met at school in a drama club, and who, at her invitation, is staying with us because it’s between quarters at the university and the dorms are closed. Lynne, who took pity on him and told him he could stay with us until the dorms re-opened, has flown away to work, leaving me alone with him.

For forty-eight hours, John has been watching television and eating everything in sight. He is a veritable vacuum cleaner for food: chips, vegetables from the crisper, canned goods, dried fruits—our entire larder has been disappearing at an alarming rate, and we have no money to replace what he has devoured. Of course, John didn’t bother to bring any food and hasn’t offered us compensation for what he is eating. I am already pissed at him for making a stylized pass at Lynne, under the guise of an audition for a play he is directing.

About once an hour for most of the day, I’ve crawled out from under the car, stood up achily-breakily, and gone into the house to politely ask John to please help me by turning the steering wheel as I try to maneuver the transmission into place. Each time, he has halfheartedly come outside, moved the wheel listlessly a couple of times, and then gone back inside to fry some more potatoes and watch another episode of Gilligan’s Island. He has no grease under his nails, no leaves in his hair, and I’m beginning to hate him for it.

I can’t remember, more than twenty years after the fact, what John had eaten that finally set me off, but when I went in to make some lunch and found the makings gone, I let him have it. “You cocksucker,” I said. “You sit here in my house and eat my food and watch my television and you would screw my wife if you could, and yet you can’t be bothered to get off your ass and help me for a few minutes. Get the fuck out there and grab that steering wheel, and if you let go of it before I tell you to, you’d better be gone when I come out from under the car.”

John, wide-eyed, grabbed a flashlight, ran outside, and obligingly maneuvered the wheel until I worked the transmission around the steering arm. I don’t know what made me feel better—that transmission sliding into place after two days, or John’s fear of a crazed 250-pound Belushi-like madman. For a brief, shining moment, being a man didn’t seem like such a bad deal.

But nearly every other moment of my life, I resented my maleness. I hated the social expectations forced upon me by my gender. When I was a teenager, I wanted to talk with the girls about feelings and relationships, but that would have been dangerous. Instead, I talked about things, and occasionally, about women as things, with the boys. I learned to type by banging away on a 1930s-model Woodstock typewriter left over from my mom’s high school days; typing class was for girls and for boys of questionable sexuality and I was afraid to sign up. I would have liked to have taken Home Economics; instead, I made a lamp (and not a very good one, I might say) out of a bowling pin in shop class. My father wanted me to play football, a game I considered hopelessly competitive. I remember thinking, “Why, if everyone would just cooperate, we could run up thousands of points for each team, and make sure the game ended with a tie. Everyone would win.” Even though I was smart enough not to suggest such a strategy to the coach, my football career lasted only a week. I just didn’t have the necessary competitive mentality. No, scratch that. I refused to put up with the macho bullshit.

When I was in my late teens the Viet Nam War was raging. Instead of staying home with the women, I was expected to register for the draft and go when called to fight a senseless war in service of politicians and generals and Wall Street. I didn’t want to kill anyone, and I saw no honor or glory in coming home in a box. I thought I might head for Canada if I was called. Fortunately, my draft number was 251, and I didn’t have to make that decision.

When I married, Lynne expected me to work on the car and mow the lawn. I was happier and at least as efficient as she at cooking and cleaning the house, even without the valuable early experience of Home Economics. We should divide the chores by ability, and not by gender epectations, I told her, but the best deal I could manage was to add cooking duties to my list of chores and mowing to hers.

I could never bring myself to don the male business regalia, the suit and tie. My male uniform was jeans, casual shoes, and long hair. There were only a few times, mostly at weddings, when I had to hang an tie around my neck, shrug into a suit, and go play Man for a few hours.

I especially resented the expectation that because I was male, I would move heavy objects. I was an feminist, and I didn’t acknowledge the inferiority of women, at any level, even physical— hell, let them use leverage, they can get them boxes in, the testosterone in me said—but being Southern bred, I would always do as I was bidden.

Had my dissatisfaction with maleness been limited to social expectations, I might have been able to cope with manhood, but that wasn’t the case. In addition to my distaste for the male role, I had a deep and lasting loathing of my body, or rather of the type of body that fate and testosterone seemed to have dealt me.

I hadn’t particularly minded being a boy, but manhood brought the oily feel of testosterone on my skin and in my hair, the sudden rages, the high sex drive. I abhorred it all. I would much rather have had a female body, and eventually figured out how to have one, but for all that, the male body could be pleasurable, if I set my mind to it. For instance, I didn’t particularly want a penis, but since it was there, I figured, why not use it? I can honestly say my pecker and I had some really good times together. Not that I’m not glad it’s gone—I am—but it was okay while it lasted. I didn’t want facial hair, either, but there it was: why not grow a beard? And so I did.

Still, I hated the things testosterone did to my body, making my voice drop, giving me whiskers and hair on my chest, making my skin and hair oily, yada yada yada. But most of all, I hated losing my hair. Every strand I found in my comb was another sign of a battle lost to the dreaded male hormone.

I think the reason I resented my maleness so much was that I wanted so badly to be a female. From age 13 or so, all I had ever really wanted out of life was to be a girl. I would crossdress at every opportunity, and by luck of the draw, I had a physique—delicate facial features, smooth throat, small-pored skin—which allowed me to see how I would have looked had I been an actual girl. With my short hair blended into a fall, my eyes made startlingly large and innocent by the addition of eyeliner and false eyelashes (it was the ’60s; everyone was wearing them), and my cheekbones enhanced with blush, I would step into a short purple dress I dearly remember, and my maleness would be temporarily eradicated. In the mirror I would see not a crossdressed boy, but a very pretty girl.

She was a fiction, that young woman, someone who had to go back into the box before my parents came home and discovered her, but she afforded me a glimpse through the Looking Glass. I wanted, I desperately desired to be her, but my maleness prevented her from manifesting permanently. I had to work really hard to make her appear. I had no idea how to make her a reality, but I was very nearly consumed by the need to do so.

I now know the girl in the mirror was to a large extent a fantasy. She was real only for the moment, a fabrication not only of my wish to be a girl, but of my sexual desire as a boy. She was a blank canvas for my expectations and sexual desires, my transvestite fantasy, and I loved her and desired her, and at the same time I would have given anything to be her.

The girl in the mirror was fifteen. I’m forty-nine. I’ve been living and working as a woman for nearly ten years, and am more than seven years past sex reassignment surgery. And guess what? I’m not the girl in the mirror. I’m a forty-nine year old woman, no more, no less. I’m not a caricature. I’m not a stereotype. And I’m nobody’s transvestite fantasy, not even my own.

My personal decision to change sex wasn’t an easy one. It was predicated on a number of factors, including the aforementioned feminine facial features, a long history of successfully passing in public while crossdressed, being unencumbered by marriage (Lynne and I were divorced in 1977), children, social circumstances, education, or career, and by my lifelong desire to be a woman. I remember staring in the mirror, making a careful self-evaluation, asking myself whether, ten years down the road, I could be sufficiently feminine in appearance and demeanor to have a normal life; if I was going to excite comment wherever I went, I wasn’t even going to start. It seemed to me the go for it factors just barely outweighed the live with it factors. I eventually decided that as great as the risks were, the potential benefits were far greater. Like Michelangelo, I saw the finished product in the chunk of marble, and I went for it.

Somehow I found the courage to bring about the physical and social changes that would enable me to live as a woman, even though at least one gender clinic told me I wasn’t transsexual because I was “not dysfunctional enough” as a male. It seemed I didn’t share those two stereotyped hallmarks of male-to-female transsexualism, a hatred for my penis and a history of femininity from a young age. I wondered at the time whether I was transsexual or just a man who wanted to be a woman, and on occasion, I still wonder. Who knows? Who cares? What does it matter? I became a woman, and I not only have no regrets, it was the best thing I ever did for myself.

By the time I finally worked through my feelings and embarked on the first scary steps of sex reassignment, the girl in the mirror was long gone, without even a photograph to document her existence. Gone also is the young man I once was. When I examine old photographs, I see little resemblance to the youth smiling back at me. There seems to be no continuity, no way that person could have slowly changed into this person. And yet I remember the soft pubic-hair feel of my beard, the gravel in my back and the leaves in my hair and the weight of the transmission on my then flat chest.

My body has changed. My chest is no longer flat; my center of gravity, and perhaps the center of the universe, has changed. When I reach into my forbidden area, I feel something wet and warm and inward, and not a slab of flesh, a protrusion. My face is smooth, with no trace of hair on it, except for the fine vellus hairs all women have. Even my voice seems to have changed.

My psychology has changed also. I’ve become a milder person, disassociated from the behavior and speech patterns which I once displayed, and yet I remember with pleasure stalking into my house to browbeat the evermunching John into helping me with that transmission.

In my own journey, my dissatisfaction stemmed from the fact that being a man is physically and socially incompatible with being a woman. By that, I mean that I changed sex because I wanted to be a woman, not because I didn’t want to be a man. I realize now that my visions of manhood and womanhood were limited by the cultural blinders of the time and by my own then sexist and stereotyped notions of what men and women were like, especially in relation to myself. As a man, I had a need to conform, to appear masculine, and consciously fought any appearance of androgyny or bleedthrough of the femininity I so obviously felt. I didn’t lisp, I did not mince, I didn’t affect physical characteristics which would make me “suspect.” I couldn’t allow myself to be seen by others as feminine, or homosexual, or even androgynous. This was a terrible burden and, I now realize, a senseless one.

As I pursued my own process, my notion of what a man is began to change. As I became an adult and peer pressure relented, I felt more free to keep my legs shaved or to wear jewelry or to pierce my ears. I began to own who I was, to allow myself to be a different kind of man. As hormones feminized my body and facial hair disappeared with electrolysis, I grew accustomed to having people think I was a woman, even when I was doing my clever impersonation of manhood. And eventually, when I crossed over life’s Great Divide and began living as a woman, my idea of womanhood began to change. I learned women could do and be anything they darn well pleased. I grew less inclined to wear makeup, pumps, skirts, and dresses, and made myself comfortable in sweats and sneakers. I learned to assert myself. I learned to carry heavy boxes rather than exploiting men by allowing them to carry them for me.

In my process I reinvented my masculinity, and then my femininity, and achieved, for the first time in my life, unity. For me, it required a change of sex, but I suspect that for many others a reinvention of their maleness or a genderless or third-gender self-identification would bring the same sort of comfort I have found in being a woman.

I suspect that even if contemporary relaxed notions of manhood and womanhood been common back in 1964, when I first saw the girl in the mirror, I would still have reached the Final Solution I pursued, but I do know this: the journey would have been far less lonely.

Notes

[1] I know the term fag is offensive, but I can think of no better term to describe that asshat John.