You Make Me Sick! (2004)

©2004 by Dallas Denny

Sources:

Denny, D. (2004). You make me sick!: A critique of the psychological and medical literature of transsexualism. Paper presented as part of the Trans-Progressing Symposium, Fantasia Fair, 17-24 October, 2004, Provincetown, MA.

Denny, D. (1997). Needed: A new literature for a new century. Paper presented at the XV Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association 15th Symposium: The State of Our Art and the State of Our Science, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 10-13 September, 1997.

You Make Me Sick!

A Critique of the Psychological and Medical Literature of Transsexualism

By Dallas Denny

Author’s Note: I would like to thank Dr. Vern Bullough and Dr. Sandra Cole for their comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

The psychological and medical literature of transsexualism, which began after Hamburger et al.’s announcement of Christine Jorgensen’s sex reassignment some 52 years ago, consists chiefly of clinical reports and studies written by presumably nontranssexual individuals. It is a literature which has been historically based on a number of unfounded assumptions: that those with gender identity disorder (as it is now called) are mentally disturbed; that their destinies are best determined by mental health professionals; that only those who are profoundly unhappy in their birth gender should be allowed access to body-changing medical technologies, and then only after passing various tests required by psychotherapists; and that body-changing medical technologies should be used only in the service of altering bodies to resemble as closely as possible those of the “other” sex, with no intermediate states allowed or even conceivable. Only in the last few years have new writings begun to challenge these assumptions.

The assumptions which have driven the literature arose from the often sexist and homophobic attitudes of researchers and clinicians and have colored both public and private perceptions of transsexuals and transsexualism and set the course for the literature itself by determining not only the research questions asked, but the ways in which the resulting data have been interpreted. The biases of researchers are often kept overtly out of their papers, but are made clear in their conversations with other professionals. Cautionary voices of anthropologists, feminists, occasional clinicians, and transsexual people themselves have been virtually ignored. Questions of experimenter bias, subject selection, and the power dynamics of the client-caregiver relationship have not been addressed. Until recently, the voices of transsexual and transgendered scholars were entirely absent from the discourse. Consequently, the literature of transsexualism is largely pejorative, tending to blame and otherwise stigmatize transsexuals not only for their very transsexualism, but for shortcomings in research design and treatment. When the assumptions underlying this literature are understood, the literature’s failing can be seen to lie not so much in the inadequacies of transsexuals themselves as in the shortcomings of the system which arose to treat and study them, and in the disenfranchisement of transsexuals themselves, who have been considered unworthy of contributing to the literature.

Much of the existing literature, although technically accurate, addresses in detail questions which no longer seem relevant. For instance, there have been any number of studies designed to determine the ways in which transsexuals vary from controls (i.e., “normal” individuals). A great deal of effort has been expended in attempts to “manage” transsexualism and transsexuals themselves. Meanwhile, other, more important, questions remain unaddressed. We do not particularly need further studies about the relative performance of transsexuals vs. control groups on the scales of the MMPI; we need studies which will define a new literature which is less bound to the notion of the inevitability of genital surgery and Ken and Barbie stereotypes of masculinity and femininity, which empowers transsexual people rather than degrading or stigmatizing them, and which asks new questions relevant to a new century.

Although people we would today characterize as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgendered, and transsexual have always existed (cf. Feinberg, 1996; Taylor, 1996), it was not until the nineteenth century that they were came under the scrutiny of the medical profession [1]; that is, physicians selected them as fitting subjects for study and ascribed pathology to them. This is perhaps best exemplified in Krafft-Ebing’s (1894) Psychopathia Sexualis, in which one can read grim clinical depictions of century-ago analogs of modern-day homosexuals, transvestites, and transsexuals (Bullough & Bullough, 1993, pp. 204-207). Initially, variations in sexual orientation and gender expression were considered by physicians to be different facets of the same disorder, a sort of “third sex” (Ulrichs, 1994). It was not until the publication in 1910 of Hirschfeld’s Die Transvestiten that the two were adequately differentiated. In the last two decades of the twentieth century homosexuality ceased to be viewed (except by extremists) as a mental disorder, but transsexualism and other gender variabilities remain codified in the DSM with the diagnostic label Gender Identity Disorder (DSMIV-TR).

During the first half of the twentieth century, the professional literature almost uniformly viewed homosexuality as a disorder. The work of Evelyn Hooker (cf. Hooker, 1957), the removal of homosexuality from the DSM-III in 1980 (described in Bayer, 1987), the pioneering work of Masters & Johnson (Vern Bullough, personal communication), and the rise of the gay liberation movement following the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969 (Duberman, 1993) did much to change this literature. These days, the acknowledged and unacknowledged assumptions of researchers about gay men and lesbians are quite different than in the past, and from the contemporary perspective much of the earlier literature seems naive and biased. The few medical professionals, like Charles Socarides, who continue to stubbornly insist without benefit of data that homosexuals are mentally ill are forced to seek alliances with organizations like the right-wing American Family Association and in fact begin to look rather troubled themselves (cf Socarides, 1996). This sort of change of paradigm (Kuhn, 1962) is not uncommon in science; in fact, it is perhaps our only real evidence that science actually works.

Although gender-variant people have been heavily involved in the gay liberation movement since its earliest days, they have not benefitted, as have gay men and lesbians, by becoming demedicalized. Christine Jorgensen’s sex reassignment and its attendant publicity brought transsexualism firmly into the medical camp (Hamburger, et al., 1952). Suddenly there was a new type of person, one who sought access to medical technologies such as hormonal therapy and genital sex reassignment surgery in order to modify the body to resemble that of the other sex. Much of what has been published in professional journals since Jorgensen’s heyday concerns the medical management of these individuals. Papers abound on the morality (or lack thereof) of sex reassignment, the etiology, incidence, prevalence, mental state, and treatment of those who are or wish to be sexually reassigned, and the outcome of sex reassignment surgery. The primary assumption of this psychomedical literature is that anyone who wishes to have sex reassignment has an underlying mental disorder which causes great anguish, and that physicians and other professionals, who have been unable to cure this “disorder” with their armamentarium of psychoanalysis, behavior modification, pharmaceuticals and psychosurgery, may be able to alleviate the pain of a select few individuals by granting them access to body-changing technologies. A corollary of this assumption is that psychological and mental health professionals must guard the gates, vigorously safeguarding those technologies, lest they be used by those who have not met the tests imposed on them by the psychomedical community and are therefore undeserving of treatment. [2]

Harry Benjamin’s 1966 The Transsexual Phenomenon was the first serious attempt to provide a name and a theoretical framework to explain people who wished to gain access to these medical technologies. He called them transsexuals. The psychiatric condition he presumed them to have was first called transsexualism, then gender dysphoria (Fisk, 1973), and is now known as gender identity disorder (DSM-IVTR)—but transsexuals we remain.

Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment, Green & Money’s 1969 edited text, provided a multidisciplinary look at the newly conceived phenomenon of transsexualism; it provided a multidisciplinary treatment model that is followed by gender programs to this day. Benjamin’s and Green & Money’s volumes were milestones, and hold up well after 30 years, but much of what has followed has been a virtual rehash. Denny (1993) has called this literature “a collection of papers by clinicians explaining to other clinicians how to deal with such troublesome people.” It is a literature bothersome in a variety of ways, but its primary shortcoming is that it has never examined in a systematic and rational way Benjamin’s model of transsexualism or looked at alternatives to the treatment system described in Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment. Consequently, the literature has come to consider transsexualism a condition discovered rather than invented (Denny, 1997a).

The existing literature has many problems. Its themes, its assumptions, and its language make it nearly impossible to discuss transsexuals or transsexualism in a healthy way. It is on the whole profoundly disrespectful of transsexual people, who are portrayed as sexual stereotypes, ridiculed for their manner of dress, and insulted in a variety of other ways both overt and covert. It actively promotes a model disempowering to transsexuals, who have been expected to surrender their autonomy to mental health professionals and then disavow their transsexualism by disappearing into the woodwork and passing as nontranssexuals after their gender transitions. And it has historically limited choices by recognizing only two options: remaining in the sex of original reassignment, or emulating as closely as possible the other sex. Much of the literature continues to ignore the commonly-expressed fact that many transgendered individuals find it more comfortable in the nether ground between the two commonly acknowledged sexes.

The Enforced Absence of Transsexual Voices

One of the most profound but virtually unremarked problems with the literature of transsexualism is that it has excluded people with transsexualism from the discourse. Pat Califia (1997) writes:

… Transsexuals are stereotyped as patients undergoing sex reassignment, the troubled clients of psychotherapists…. This gives the experts a privileged voice and disenfranchises differently-gendered people. In autobiographical or fictional accounts, they may set down what they perceive to be true about themselves and the world around them, but it is the medical doctor, therapist, academic, or feminist theoretician who interpret “them” for the rest of “us,” and thus claim to be the voice of reality…. To be differently-gendered is to live within a discourse where other people are always investigating you, describing you, and speaking for you; and putting as much distance as possible between the expert speaker and the deviant and therefore deficient subject. (pp. 1-2)

Except for relating strictly autobiographical experiences, transsexuals have been considered to have had nothing important to say about transsexualism. Certainly, they have remained unpublished. I recently noted that until recently, all major theoretical papers, all of the descriptive studies, and all of the textbooks about transsexualism were written by nontranssexual persons. This situation is analogous to the study of Black history and identity without the involvement of Black scholars, or of gay and lesbian history and identity without gay and lesbian scholars” (Denny, 1997b, p. 75). The transgender revolution of the ’90s made it clear many transsexual persons view themselves in ways other than depicted in the psychomedical literature (cf. Bornstein, 1994; Boswell, 1991), but they were unable to share it with the world because their transsexualism silenced them: first, under the prevailing reign, if they spoke the truth they were considered not to be “true” transsexuals and risked being denied access to body-changing medical technologies (see Bolin, 1988; Denny, 1992; Kessler & McKenna, 1978; and Stone, 1991 for critiques); and second, no one would publish their work. Is it any wonder perceptions of transsexuals and transsexualism have entered a period of intense change now our voices are being heard?

Even words that seemed as if they might have been written by a transsexual had led to exclusion from peer-review publications. Both Denny (1997b) and Cromwell (1997) have documented the rejection of a paper by Bolin; on the margin of one of the copies returned to her was the scrawled comment of a reviewer: “Obviously a transsexual.” Unwritten were the words, “… and so, this paper is inherently biased and not worthy of publication”). Acknowledging this problem, Richard Green (1997) noted of Denny’s 1997c edited text, “Startling as it is for me to think it, I wrote the conclusion to Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment about 25 years ago…. I am struck at the outset that the biggest change with this new text may be that it is edited by a transsexual.”

In the past several years, transsexual and transgendered persons have begun to contribute meaningfully to the literature and much of what they (I should say we, as I am proudly transsexual) have to say is dramatically different from what has previously been published. We tend to be influenced not only by the medical and psychological literature, but by feminist and queer theorists, by each other, and of course by our own experiences. Queer and transsexual and transgendered scholars bring a different vision to the table, for we tend to look at the desire to change one’s body and social role not as a sign of psychopathology, but as a form of self-expression not dissimilar to getting a tattoo or having a rhinoplasty. The problem, if any, is seen to lie not within us, but within a hostile and rejecting society that cannot or will not accept us as we believe we are (Califia, 1997; Wilchins, 1997). Gender identity disorder is a term coined by the medical community to ascribe pathology to what is actually a healthy process of self-discovery and personal growth. In this view, much of the literature is flawed by this presumption, which causes in its adherents a peculiar tunnel vision in which transsexualism is seen as a journey from one restrictive gender role to the other, equally restrictive role, and transsexuals themselves are constructed to fit this model (Bolin, 1988; Denny, 1992; Stone, 1991). Transsexual and transgendered scholars reject this bipolar model, considering that acceptable gendered space lies anywhere along the continuum between male and female, or off the continuum altogether (Boswell, 1991). The idea is not to produce new males and females who conform as closely as possible to existing gender norms, but to help people unhappy in their assigned gender role to find gendered space they find comfortable C wherever that may be.

My ultimate purpose in this paper is not to debate the merits of lack thereof of social-constructionist vs. essentialist approaches to transsexualism. [3] I do, however, wish to give examples of the ways in which the medical and psychological literature has vilified and stereotyped transsexual men and women. I have used selected quotations to illustrate my points. My quarrel is not with the individual authors, but with the literature itself.

The Medical and Psychological Literature of Transsexualism

The Benjamin model has been attacked from a variety of perspectives, including psychiatry (Wiedemann, 1953; Socarides, 1976; McHugh, 1992), feminism (Greer, 1989; Raymond, 1979); social constructionism (Billings & Urban, 1982; MacKenzie, 1994) and Christianity (O’Donovan, 1982, 1984). The hostility of authors like Socarides, McHugh, Greer, and Raymond is without parallel in any field of science. Raymond (1979), for instance, writes of Dr. Renée Richards, “It takes (castrated) balls to play women’s tennis” (p. xiii). McHugh (1992) cited “the confusions imposed on society where these [transsexual] men/women insist on acceptance” and “the sad caricature of the sexual reassigned” (pp. 503, 509). Socarides says of sex reassignment surgery, “The creation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein monster pales in comparison with this grotesque spare-parts, Tinker-Toy type of surgery practiced on living, suffering, and desperate human beings” (1976, p. 138). Not surprisingly, none of these authors cite empirical evidence to document their often outrageous claims, and none offer significant data of their own. None, in fact, have interacted to any significant extent with transsexual people. [4] Their work is opinion disguised as science, and it is venomous almost beyond belief.

But if the enemies of sex reassignment have been uncritically critical, so, too, have many of its supposed proponents. Much of the supposedly objective literature is characterized by moral pronouncements, outrageous attacks on the nature and appearance of transsexual people, and the use of nomenclature and pronouns which are offensive (deliberately, in some cases) to transsexual people. This is but the visible tip, however, of what lies under the surface of a literature which presumes that transsexuals are what the medical community has always supposed them to be: manipulative, dishonest, maladjusted, sexual stereotypes. It is a literature which gives permission to its authors to write whatever they wish about transsexuals, with no fear of censure.

Occasionally, authors will unabashedly state their moral distaste for sex reassignment. For example, Donald Laub and Norman Fisk wrote in the journal Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in 1974, “To change an individual’s God-given anatomic sex is a repugnant concept.” It goes without saying that such a gratuitous remark has no place in a surgical journal—or does it? Apparently, this amazing statement went entirely unremarked until 1991, when I pointed it out in Chrysalis, a journal I edited.

At other times, an author’s distaste for transsexuals will suddenly surface like a Freudian slip in an otherwise nonjudgemental descriptive passage, as in the second sentence of the following:

The realistic assessment of gender-dysphoric patients must take into account that there are some individuals who could never pass as members of the opposite sex, regardless of how skillfully they are dressed and made up. A six-foot-five, 300-pound trucker will never pass as a woman, but will always look like “a guy in drag. (Steiner, 1990, p. 102)

Less subtle was psychoanalyst Robert Stoller, who frequently and vociferously made known his concerns about sex reassignment. He wrote, of transsexuals and sex reassignment, “After 30 years… both the treatments and the patients (of both sexes) have been, at most, near misses” (Stoller, 1982, p. 283). In this sentence, Stoller informs the reader of his opinion that male-to-female transsexuals are not “really” women.

Tongue-in-cheek remarks like Stoller’s, above, were not uncommon. Witness Money and Primrose’s (1968) sly put-down of transsexuals who took the initiative to learn about what was going on with them:

Transsexuals… are distinguishable from females at large by their lack of special attraction to the helpless newborn and their imagery in coital fantasies. It is possible, though, that transsexuals will change their conception of the female stereotype to include these features after reading this article, since they are often influenced by reading about their condition. (p. 472)

Money & Primrose’s remark illustrates a phenomenon pointed out by sociologist Irving Goffman (1961, 1963): when an individual is stigmatized, whatever he or she does is interpreted and interpretable as problematic in light of the stigma. Thus, when transsexuals endeavor to learn more about their situation—something that would be considered admirable in expectant mothers or individuals with sickle-cell anemia—their resourcefulness is viewed as emblematic of their condition.

There have been grave problems with a lack of respect with the terminology of transsexualism. The widespread use of terms such as “male transsexual” and “female transsexual” to refer, respectively, to male-to-female and female-to-male transsexuals, are offensive to transsexuals (Cromwell, Green, & Denny, & Cromwell, 2001), but the terms are generally not used maliciously. The same cannot be said of pronouns. In the psychomedical literature, authors wield pronouns like swords, using them to express their disapproval and pronounce the “true” sex of transsexuals. By far the worst offenders are Janice Raymond and Leslie Lothstein. Raymond’s (1979) book is a political manifesto unconvincingly (and in my opinion unethically) disguised as science. Lothstein’s (1983) book on female-to-male transsexualism is egregiously offensive. He not only uses female pronouns to refer to subjects who live as men, but refuses to use their male names, calling them by their original female names, which no longer match either their appearance or the realities of their lives. “It was hard to believe that the cocky, self-assured ‘male’ sitting in the waiting room was really a biological female” (Lothstein, 1983, p. 95). Note how Lothstein uses quotation marks to tell the reader his subject is not “really” male.

Considering that Lothstein is a male with the first name of Leslie, one might think that he would be aware of the pain pronoun misattribution can cause. Should I turn the tables and refer to Ms. Lothstein and her regrettable book, turning Lothstein into a female on paper, it becomes clear how disrespectful such pronoun misuse really is, that I am attacking Lothstein on a personal basis. This is because it has long been considered appropriate for others to make decisions about which pronoun to use with transsexuals, regardless of the self-perception of the transsexuals themselves, but it is decidedly not okay to do so with nontranssexuals. Quite simply, with it comes to transsexualism the usual rules of propriety do not apply, and no one seems to notice that they have been set aside, even in the hallowed pages of medical and psychological journals.

The severity and intensity of some patients’ psychopathology and acting out were… revealed within the group, for example, two members brought loaded guns into the group (One member had to be forcibly restrained from using it!); auto- and mutual masturbation; exposure of breasts; an attempted kidnaping; several near-violent confrontations among group members which carried over outside the group (in which patients threatened each other physically and one patient drew a knife); innumerable sexual overtures to the therapists; patients bringing in pets (two dogs and a menagerie of land crabs); serious psychosomatic symptoms (including ulcerative, arthritic, hyperventilative, and cardiac distress). (Lothstein, 1979, p. 73)

Most of our surgically treated patients had a long history of arrests and convictions for minor nonviolent crimes, especially prostitution…. In addition to a long history of petty criminal offenses, they dressed in dramatic seductive fashion, passed convincingly as women, had a history of passive participation in homosexual activity, and seemed to have fully adopted the feminine gender role late in adolescence. In addition they were manipulative, demanding, and therefore troublesome in their behavior…. Most of the patients in our series had histories of having taken drug overdoses and some had been hospitalized psychiatrically during their turbulent years preceding and just after beginning to live fulltime in the feminine role. (Stone, 1977, p. 26)

Choice of words, especially when used to describe transsexuals, tends to reinforce the prejudices of authors and readers alike. Take a look at the word usage of Lothstein (1979) and Stone (1977), in the passages above. They tailor their language carefully to paint strong word pictures of clearly deviant individuals. Consider also the previous passage by Steiner, and the following, also from Steiner (1990):

Some biological males cross-dress in such a convincing manner, with discrete makeup and tasteful jewelry, that they “pass” as women without ever having commenced feminizing hormones. Others would pass if they were not so flamboyant! Strange esoteric hairdos and immensely long artificial nails like talons (usually painted a bright scarlet) may grossly exaggerate such patients’ appearance in a caricature of “femininity.” (p. 101)

It goes without saying that many nontranssexual women wear long nails, or are less than discrete with their hairdos, makeup and jewelry. The literature clearly gives Steiner license to ridicule the appearance and grooming of transsexual women in language she would never use if she were talking about nontranssexuals. Can you imagine the stir the above paragraph would have caused had it been applied to African-American or Republican women?

Of course, gender professionals’ own appearance is appropriate, whatever they choose to wear. For your amusement, the following, from a transgender community flyer, circa 1980:

She arrived late, having been delayed in a “clinic.” Most of the audience was slightly taken aback as she appeared in a tight figure-hugging fire-engine red dress with sides slit up her thighs and beige spike heels, her long straight very, very blonde hair falling sensuously over her eyes. [Name deleted] had definitely out-transvestited the transvestites, who wondered what kind of “clinic” she had just left!

The literature is filled with sweeping generalizations of transsexuals; the sky is the limit: “These (secondary transsexual) individuals do not pass easily in the opposite gender role without the aid of hormones and electrolysis. Their natural voice is quite masculine, numerous expensive cosmetic procedures are often necessary before they can approach the total femininity they seek.” (Dolan, 1987). “All transsexual biological females are homosexual in erotic object choice, and all of them wish to have a penis…” (Steiner, 1985, p. 353). It goes without saying that many secondary transsexuals and some male crossdressers are quite passable and in fact rather attractive without hormones or electrolysis, and more than a few female-to-male transsexuals identify as gay men (cf Allen, 1989; Cameron, 1996).

Generalizations about transsexuals go beyond appearance to behavior. As late as 1993, one gender program’s application included the question, “How often have you used prostitution as a means of supporting yourself?” It was presumed that male-to-female applicants had of course prostituted themselves. Such questions are not asked of persons seeking treatment for other conditions; it is simply acceptable to ask such questions of transsexuals, but of course, it would not be appropriate to do the same with persons with heart disease or diabetes.

Professional journals contain a number of articles which should never have been published. By portraying transsexuals as deviant, the literature opens publishing avenues for articles which reinforce this perception, however undeserving they may actually be. Milliken (1982) opened a paper titled “Homicidal Transsexuals: Three Cases” by stating that transsexuals are known to be overall less violent than the general population; he nevertheless then searched until he found three transsexuals who had committed or attempted to commit murder. Psychiatrists are arguably less violent than the general population; however, I know of no papers titled “Homicidal Psychiatrists: Three Cases.” If I were to write one, there would be little chance of it being accepted for publication in a peer-review journal.

Because the literature presumes transsexuals to be incapable of making informed judgements about altering their bodies with hormones and surgery, they are assumed to be unable to make other decisions for themselves. Special precautions are needed even for transsexuals who ask for a rhinoplasty:

With patients over the age of 30, great care must be taken not to alter nasal contours or size too greatly, as the older patient may experience a sense of loss of identity with associated postoperative crisis. (Edgerton, 1974; emphasis in original)

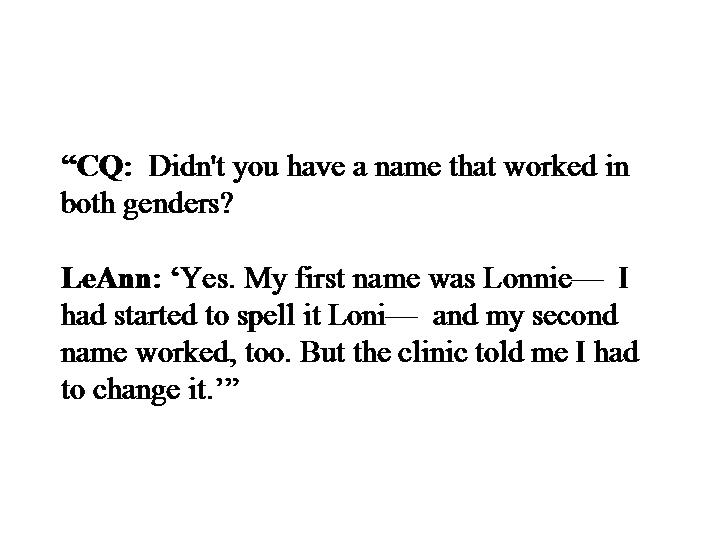

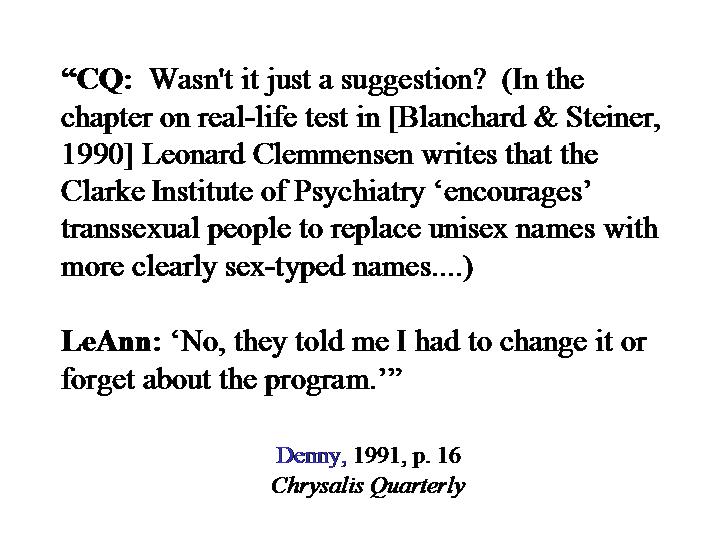

Indeed, professionals have not only told transsexuals what to wear and how to behave, and what to do with their noses, they have been so presumptuous as to tell them what names to use, what sort of jobs they should have, and who they should be sexually attracted to, and have even insisted that legally married transsexuals must divorce. Although they are generally vouchsafed in the literature as “recommendations” (cf Clemmensen, 1985), these are generally requirements, with the price of noncompliance being the withholding of hormones or surgery or rejection from the program. The following is an excerpt from Denny (1992); LeAnn is talking about the very clinic Clemmensen (1985) described as “recommending” its transsexual clients assume gender nonambiguous names:

CQ: Didn’t you have a name that worked in both genders?

LeAnn: Yes. My first name was Lonnie. I had started to spell it Loni, and my second named worked, too. But the clinic told me I had to change it.

CQ: Wasn’t it just a suggestion? (In the chapter on real-life test in [Blanchard & Steiner, 1990] Leonard Clemmensen writes that the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry “encourages” transsexual people to replace unisex names with more clearly sex-typed names….)

L: No, they told me I had to change it or forget about the program.

—p. 16

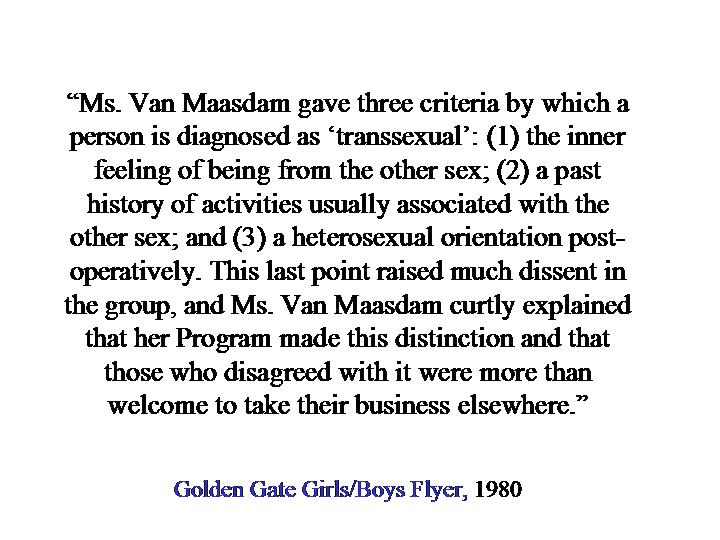

Following is a paragraph from “What;s Wrong with Stanford?” a one-page flyer distributed around 1980 by Golden Gate Girls & Guys, a transgender support group. It describes a question-and-answer session with Judy Van Maasdam of the Gender Dysphoria Program in Palo Alto (formerly the Stanford Gender Program).

Ms. Van Maasdam gave three criteria by which a person is diagnosed as “transsexual”: (1) the inner feeling of being from the other sex; (2) a past history of activities usually associated with the other sex; and (3) a heterosexual orientation post-operatively. This last point raised much dissent in the group, and Ms. Van Maasdam curtly explained that her Program made this distinction and that those who disagreed with it were more than welcome to take their business elsewhere.

Clearly, this “our way or the highway” mentality signifies professional arrogance. Such arrogance was common in gender programs in the 1970s (Denny, 1992). And of course, responding to this type of manipulation, transsexuals learned to lie to their caregivers about their sexual orientation. Needless to say, they were then blamed for being manipulative and dishonest.

The preoperative individual recognizes the importance of fulfilling caretaker expectations in order to receive a favorable recommendation for surgery, and this may be the single most important factor responsible for the prevalent mental-health medical conceptions of transsexualism. Transsexuals feel that they cannot reveal information at odds with caretaker expectations without suffering adverse consequences. They freely admitted to lying to their caretakers about sexual orientation and other issues. (Bolin, 1988, p. 63; emphasis mine.)

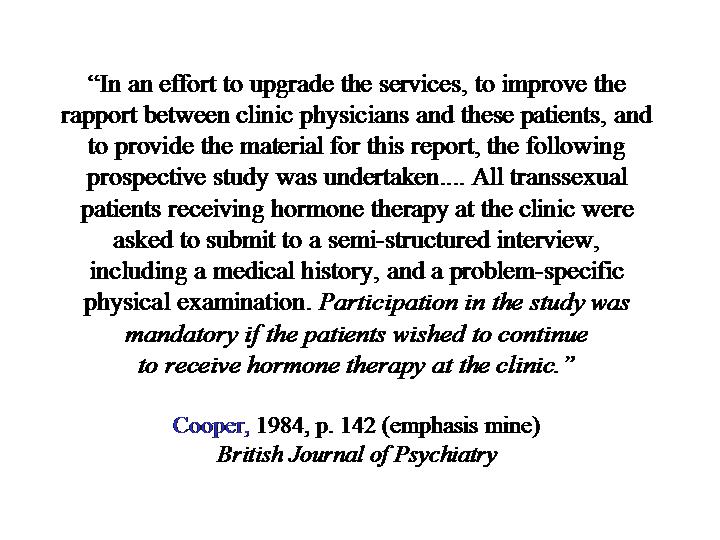

Abuse of the client/caregiver relationship by professionals has been widespread. The literature shows that transsexuals have been denied access to hormones and surgery because clinicians felt they would not be available for follow-up [“… the probability of being able to maintain (postsurgical) contact with the patient is one of the factors assessed before sex reassignment” (Steiner, Zajac, & Mohr, 1974)], or even for refusing to participate in experimental programs:

In an effort to upgrade the services, to improve the rapport between clinic physicians and these patients, and to provide the material for this report, the following prospective study was undertaken…. All transsexual patients receiving hormone therapy at the clinic were asked to submit to a semi-structured interview, including a medical history, and a problem-specific physical examination. Participation in the study was mandatory if the patients wished to continue to receive hormone therapy at the clinic. (Cooper, 1984, p. 142; emphasis mine.)

I wrote Dr. Cooper about this paragraph, and he assured me participation in his study was not mandatory in order to receive hormonal therapy. His article, however, argues otherwise.

Under the medical model, transsexuals are seen as blameworthy, not only for their condition, but for other things that are wrong with the world. Raymond (1970) scolds them for perpetuating the binary gender system; it’s as if she expects transsexuals to be some sort of gender heroes/heroines, and is lashing out at them because they have somehow disappointed her (one wonders why, if Raymond believes traditional gender roles should be deconstructed, she colors so carefully within the gender lines herself). Transsexuals are also sometimes considered at fault for the shortcomings of the medical model, most notably for the well-known problems with follow-up (Stoller, 1982). It’s hardly surprising that transsexuals, who were trained by gender programs to assimilate into society, did so, thereby becoming “lost to follow-up.” It’s perhaps to be expected that transsexuals who were frequently manipulated by the gender programs would have some enmity towards them, and so would be motivated to make themselves less than available for follow-up for which they were often expected to pay the cost (see Stone, 1991). Such eventualities were, of course, never considered by the gender programs workers. Denny & Bolin (1997) , who conducted a follow-up study outside the clinical setting, recently reported a rather surprising finding: almost 100% of more than 100 members of a transsexual support group were available for follow-up, some as many as five years after leaving the group. Group members in fact were part of a cohesive social support network which maintained long after their gender transitions. It would seem likely that the infamous problem with follow-up is actually a problem with the medical model which was used in previous studies; transsexuals have been unfairly blamed.

More insidious than overt hostility toward transsexuals is the way in which the presumptions about transsexuals’ pathological states can overshadow clinical judgement. Consider the following:

It is interesting to note that no female-to-male transsexual has currently requested [cosmetic surgery in addition to genital sex reassignment surgery and breast reduction for female-to-males]. This request appears limited to the male-to-female transsexual, which is in keeping with the greater frequency of personality disorders such as narcissistic or histrionic types, which occur more frequently in males. (—Steiner, 1985, p. 339)

Steiner chooses to interpret the differential rates with which male-to-female and female-to-male transsexuals request cosmetic surgery as due to differences in personality factors; she overlooks the fact that cosmetic surgery is often necessary if male-to-females are to present successfully as female—a trait Steiner considers important; note her passages above. Female-to-male transsexuals typically pass quite well without any intervention other than hormones and top surgery. Feminine features like a small nose or lack of an Adam’s apple are unlikely to cause an otherwise masculine individual to be perceived as female, but the observe is not true (Kessler & McKenna, 1978). Males in our society only occasionally have plastic surgery to make them appear more ruggedly masculine, but surgeons are frequently called upon by women to feminize their faces and bodies. When transsexuals follow the same pattern, male-to-females are characterized as having personality disorders, and female-to-males as being psychologically healthy.

Because the literature views gender variance as undesirable, it has eschewed exploration of third-gender roles or androgyny in favor of binary gender norms. Transgendered and transsexual persons must either be cured or helped to assimilate as members of the “other” gender; there is no middle ground. It is but appropriate and reasonable to use techniques, however intrusive, to eradicate transgender behavior, however benign. Even exorcism is worthy of consideration as a tool to “cure” transsexualism (Barlow, et al., 1977).

The excesses of behaviorists, in particular, have been legion (see Denny, 1994d, for a review of the literature with adults). Some of the experiments have been more than a little reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange.” Cooper (1963), in an attempt to control a man’s crossdressing, kept him awake for one week with amphetamines and gave him drugs every hour to make him violently nauseous while requiring him to view pictures of himself crossdressed. The subject developed cardiac problems and had to be hospitalized for a month. Incredibly, while the author lamented not having scheduled regular EKG, neither he nor his contemporaries considered that his treatment may have been a bit overzealous. Barker, in 1965 in comparing the effectiveness of electrical shock and purgatives in the treatment of transvestism, never mentioned the use of nonaversive techniques, and he certainly never discussed the possibility that the subjects might be counseled to accept their need to crossdress and integrate their crossdressing into their lives rather than being repeatedly shocked or made nauseous.

In the literature, behaviorists, who are ordinarily extremely sensitive to the fears of their critics that they will use behavioral techniques for purposes of social control, have engaged in just that sort of social engineering with adult transsexuals and crossdressers, and with almost no printed debate about its appropriateness. [5] This has not been true with other subject populations. For example, the use of aversive procedures with persons with developmental disabilities now requires multiple levels of peer and external review, and is discouraged both by administrative regulations and by consensus of those working in the field (LaVigna & Donellan, 1986). As usual, gender-transgressive individuals are exempt from protections afforded other vulnerable populations

Because professionals, rather than those with lived experience, have been considered the ultimate authorities on transsexualism, the literature has tended to perpetuate myths and misinformation. Transsexuals themselves have been unable to correct these mischaracterizations. It has frequently been claimed that transsexuals have stereotyped notions of manhood and womanhood (see Bolin, 1988, Ch. 8 for a review). In my experience, and in the experience of those who have taken the trouble to study transsexuals outside the clinical setting, this is no more true for transsexuals than for anyone else, although transsexuals frequently report feeling they had to dress and behave in gender-stereotypical ways in order to please their caregivers (Bolin, 1988, 1994; Cromwell, 1997; Denny, 1997d). Nor do all transsexuals hate their genitals, as has been frequently claimed. Many masturbate frequently, a trait generally considered to be a contraindication for surgery, and a behavior about which a great many transsexuals have lied to a great many clinicians (Stone, 1991). In a thousand ways, transsexuals are unlike what has until recently been written about them, but they have been forced to conform or risk being denied access to hormones and surgery.

The hubris of professionals can be almost without bounds. For decades, it was assumed that almost all male-to-female and all female-to-male transsexuals were heterosexual after surgery. Lou Sullivan, a female-to-male transsexual who identified as a gay man and refused to hide or lie about his sexual orientation, was able to obtain surgery only after a concerted and energetic campaign to educate professionals (Pauly, 1992; Sullivan, 1989). The reality of Sullivan’s sexual orientation was too apparent; he died of AIDS in 1991—and yet in 1996, a clinician insisted to me that were no gay-identified female-to-male transsexuals. Ironically, I must even now cite a professional source as well as Sullivan’s own work in order to document the fact of his homosexuality.

In retrospect, it is professionals, and not transsexuals, who were more likely to have been stuck in a Rambo/Bimbo limboland. They have consistently projected their often sexist notions onto transsexuals. Kessler & McKenna (1978) have noted that those turned away by one program included Puerto Ricans, who “looked like fags” to the gender clinic doctors (p. 118). They note also that one prominent clinician turned away male-to-female transsexuals whom he did not find sexually appealing (p. 118). When transsexuals, desperate for treatment, conformed to professionals’ Ken and Barbie notions, it merely confirmed and perpetuated the expectations generated by the literature (Denny, 1992).

The Impact of the Psychomedical Literature on the Standards of Care and the DSM

While a thorough discussion of the ways the literature has impacted transsexual lives would be enlightening, it would be a formidable task. I would like, however, to mention the effect the literature has had on two widely-disseminated and often-referenced protocols. The Standards of Care of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, Inc. (Walker, et al., 1984), which were first introduced in 1980 as a set of minimum consensual guidelines for the hormonal and surgical treatment of transsexualism. They presuppose that transsexuals are incapable of making their own decisions about treatment and give gatekeeping power to mental health professionals for treatments which are available to nontranssexuals without such gatekeeping. Nearly twenty years after their introduction, the same suppositions rule and have even gained in strength; the most recent proposed revision increases the gatekeeping power of mental health professionals over transsexuals (Levine, 1997). Until recently, they defined the breasts of female-to-male transsexuals as “genitals,” which they clearly are not. Bolin (1992) has pointed out that such characterizations are based on the view of female bodies as commodities. Transsexuals themselves become commodities under the Standards of Care. For example, a recent flyer for a professional workshop called “Managing the Transsexual” (a vision of a lion-tamer with a whip and chair comes immediately to mind) enticed professionals by promising a highly motivated audience which was willing to pay cash for psychological and medical treatment.

Not only do transsexuals find their autonomy limited by treatment protocols; they now have a mental illness. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association, 3rd edition (DSM-III, 1980) saw the inclusion of gender identity disorders for the first time. DSM-IV (1994) includes categories for both Transvestic Fetishism (302.8) and gender identity disorder (302.85), replacing the DSM III-R’s (1987) diagnosis of Transsexualism. The DSM-IV’s language has been roundly criticized by Wilson (1997), who finds that it and its supporting materials (Spitzer, ed., 1994) perpetuate negative stereotypes about transgendered and transsexual persons by the use of demeaning images and terminology. Wilson notes among other things that (1) the DSM-IV casebook describes a male who crossdresses as “The Fashion Plate;” (2) the DSM-IV categorizes transvestic fetishism with criminal behaviors like pedophilia and exhibitionism; and (3) the DSM-IV “blames the victim” for discrimination suffered by gender-variant people at the hands of society. Inclusion in the DSM is of little benefit to transsexuals, who, despite psychiatric diagnosis, are routinely denied insurance benefits for hormones, surgery, and counseling, and who, because they are categorized as mentally ill, frequently find themselves losing their jobs or custody of their minor children. Several years ago, Dierdre McCloskey, a prominent economist, was involuntarily psychiatrically hospitalized when she announced her decision to undergo sex reassignment. While it’s unclear what, if any, role the DSM played in McCloskey’s hospitalization, it was certainly available to provide a psychiatric label for what was in fact a well-considered and rational decision (McCloskey, 1996).

The Standards of Care and the DSM were prepared by committees which drew heavily upon authoritative published material about transsexualism. Now they in turn are considered authoritative. They are nevertheless based upon a flawed and pejorative literature, and continue the faulty assumptions, sexism, and negative stereotypes of that literature. There is little doubt that they will come under increasing attack from activists, and little doubt that they will fall under the weight of their own shortcomings.

The psychomedical literature of transsexualism is self-influencing, like a snake swallowing its own tail. It invites a certain understanding of transsexualism, and suggests certain directions for future research, which is done in due course and which in turn finds its way into the literature. Those most directly influenced by it are those who produce it; they tend not to see its recursive nature; they are simply too close to it.

The careful reader may note that most of the articles and books I have chosen to use as examples predate 1991. There are two reasons for this. First, time, even a few years, gives us a perspective that is lacking with the more recent literature; and second, there has been considerable improvement during the past ten or so years. Certainly, however, the literature continues in large part in its previous vein; it is simply disparaging transsexuals in more subtle ways. We will probably have to wait a decade or so to document that fact. However, I will give one recent example of a paper which is colored by an author’s assumptions about transsexuals.

Lothstein (1997), argues that interacting with prospective clients outside the consulting room can be “dangerous to our profession” (p. 273). That seems strange enough to those of use who are both transsexual and professionals and who have not considered ourselves in danger from transsexual acquaintances, friends, relatives, or lovers, or when we look in our bathroom mirrors—and it would certainly seem a peculiar notion to those trained in ethology, anthropology, or other disciplines which have as their mainstay naturalistic observation. However, insight into Lothstein’s thinking is perhaps best gained by the following sentence: “Person and Ovesey (1978) even visited transvestite and transsexual support groups to learn more about the phenomenon and to clinically inform their psychoanalytic perspective on how gender is experienced outside the consulting room” (p. 273, italics mine). Lothstein’s use of the word even shows how daring, dedicated, and perhaps foolish he considers Person & Ovesey to have been for venturing into transsexual space; he makes it sound as if they were Daniel, going into the den to beard the lion. None of the more than 300 transsexual support group, group therapy, and national transgender meetings I have attended have been anything other than polite gatherings; certainly none were anything like the circus Lothstein described in his 1977 paper (see above).

A New Literature for a New Century

It will come as no surprise to the reader that it is my belief that the literature needs to be reformed. In fact, reform is underway, and I expect it would continue without any help from me. I am, however, not averse to hurrying things along.

We are in need of a new literature for a new century, a literature which is respectful to transsexual and transgendered people, and which will explore new territory without being bound by limiting beliefs. Before this can happen, the contributions of non-clinicians—anthropologists, sociologists, queer and feminists scholars, and transgendered and transsexual authors—who have been for the most part been ignored by medical and psychological professionals, must be acknowledged and their viewpoints and data incorporated into the clinical zeitgeist. Moreover, we must learn to talk about transsexuals as human beings rather than patients, for only then will we be able to discuss then in terms that do not endow them with pathology. There has been resistance among clinicians to other voices (Denny, 1993). But the literature must change, and the literature will change. My hope is it will happen sooner rather than later.

Notes

[1] This has been described by anthropologists as medical “colonization.” In much the same way European powers invaded foreign lands, subjugating the inhabitants and claiming sovereignty, nineteenth physicians and mental health professionals staked out gender and sexual variance as their own. Denny (1999) has written:

Transsexualism is rather like a land that has been colonized by conquistadors from across the seas. For nearly 50 years now this transsexual country has been flying the flag of our masters. It’s not the flag of Spain or France or Portugal or England, or even the United States. The flag of the transsexual land is a caduceus, a staff entwined by serpents. Our flag is the symbol of the medical profession. Physicians have owned this land and its inhabitants—transsexuals—registered, copyrighted, trademarked, lock, stock, and barrel, signed, sealed, and delivered.

[2] This approach can be useful when dealing with individuals who have psychological or psychiatric problems; however, the model makes it impossible to look at any transsexual or transgendered person without a presumption of psychopathology, and colors the very language used. (See Cromwell, Denny, & Green, 2001).

[3] Well, maybe just a bit. While postmodern theory can be difficult to read and sometimes seems to have its own rather opaque language, it has much of worth to say. Unfortunately, some medical and psychological professionals reject it in its entirety, usually with claims that it is antiscientific. “The difficulty with social constructionism is that it impedes science and the collection of knowledge” (Hershberger, 1997, p. 560). Hershberger is being shortsighted, for he presumes scientists and therefore science have no social agendas—and of course, they do.

What social constructionism actually attempts to do is to cast loose the moorings of science, to test unchallenged and often unconscious assumptions scientist may not even know they have. In this regard, it is indeed scientific, for it enables new viewpoints that result in reinterpretation of existing data. What essentialists are actually arguing for is to maintain the status quo, which impedes science, which is really all about the very shifts in perspective that social constructionism can facilitate.

[4] I have a letter from McHugh, written in 1994, in which he expresses his profound disbelief that a post-operative male-to-female transsexual could be sexually attracted to other women. If McHugh had spent any time with male-to-female transsexuals, he would have known that a significant percentage (probably about one-third) of post-op male-to-females self-identify as lesbian. One wonders how someone with so little knowledge of transsexualism and transsexuals feels qualified to rage about them in the pages of American Scholar, as has McHugh.

[5] In contrast to the behavioral treatment of adults, which has gone unremarked, the behavioral treatment of children (attempting, of course, to cure them for their own good) has come under heavy fire. See Zucker & Bradley (1995) for an medially-biased overview and Burke (1996) for an anti-treatment position.

References

Abel, G.G. (1979). What to do when nontranssexuals seek sex reassignment surgery. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 5(4), 374-376.

Allen, M.P. (1989). Transformations: Crossdressers and those who love them. New York: Dutton.

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd. ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd. ed., revised. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th. ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th. ed, revised. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Barker, J.C. (1965). Behaviour therapy for transvestism: A comparison of pharmacological and electrical aversion techniques. British Journal of Psychiatry, 111, 268‑278.

Barlow, D.H., Abel, G.G., & Blanchard, E.B. (1977). Gender identity change in a transsexual: An exorcism. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 6(5), 387‑395.

Bayer, R. (1987). Homosexuality and American psychiatry: The politics of diagnosis. Princeton, NJ: PrincetonUniversity Press.

Beatrice, J. (1985). A psychological comparison of heterosexuals, transvestites, preoperative transsexuals, and postoperative transsexuals. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 173(6), 358-365.

Benjamin, H. (1966). The transsexual phenomenon: A scientific report on transsexualism and sex conversion in the human male and female.New York: Julian Press.

Billings, D.B., & Urban, T. (1982). The socio-medical construction of transsexualism: An interpretation and critique. Social Problems, 29(3), 266-282.

Bolin, A. (1988). In search of Eve: Transsexual rites of passage. South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, Inc.

Bolin, A. (1992). Gender subjectivism in the construction of transsexualism. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(3), 22‑26, 39.

Bolin, A.E. (1994). Transcending and transgendering: Male-to-female transsexuals, dichotomy, and diversity. In G. Herdt (Ed.), Third sex, third gender: Essays from anthropology and social history, pp. 447-485. New York: Zone Publishing.

Bornstein, K. (1994). Gender outlaw: On men, women, and the rest of us. New York: Routledge.

Boswell, H. (1991). The transgender alternative. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(2), 29‑31.

Bullough, V.L., & Bullough, B. (1993). Cross-dressing, sex, and gender. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Burke, P. (1996). Gender shock: Exploding the myths of male and female.New York: Doubleday.

Califia, P. (1997). Sex changes: The politics of transgenderism. San Francisco: Cleis Press.

Cameron, L. (1996). Body alchemy: Transsexual portraits.Pittsburgh, PA: Cleis Press.

Clemmensen, L.H. (1990). The “real-life test” for surgical candidates. In R. Blanchard & B.W. Steiner (Eds.), Clinical management of gender identity disorders in children and adults, 119-135. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.

Cooper, A.J. (1963). A case of fetishism and impotence treated by behaviour therapy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 109, 649‑652.

Cooper, M.A. (1984). Hormone treatment clinic for transsexuals. Hawaii Medical Journal, 43(5), 142, 144, 146, 149.

Cromwell, J. (1997). Fearful others: Medico‑psychological constructions of female‑to‑male transgenderism. In D. Denny (Ed.), Current concepts in transgender identity. New York: Garland.

Cromwell, J., Green, J., & Denny, D. (2001). The language of gender variance. Paper presented at XVII HBIGDA International Symposium on Gender Dysphoria, Galveston, TX, 31 October – 4 November.

Dierdre McCloskey. Chronicle of Higher Education, (1996, February), A‑17.

Denny, D. (1992). The politics of diagnosis and a diagnosis of politics: The university-affiliated gender clinics, and how they failed to meet the needs of transsexual people. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(3), 9-20.

Denny, D. (1993). Letter to the editor: Response to Charles Mate-Kole’s review of Ann Bolin’s In search of Eve: Transsexual rites of passage. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 22(2), 167-169.

Denny. D. (1994a). Gender dysphoria: A guide to research. New York: Garland.

Denny, D. (1994b). Introduction. In Gender dysphoria: A guide to research. New York: Garland.

Denny, D. (1994c). Behavioral treatment in gender dysphoria: A review of the literature and a call for reform. Paper presented at the 20th Anniversary Conference of the Association for Behavior Analysis, Atlanta, GA, 26‑27 May, 1994.

Denny, D. (1997a). A consumer;s perspective. Address given at the XV Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association Symposium: The State of Our Art and the State of Our Science, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 10‑13.

Denny, D. (1997b). Coming of age in the land of two genders. In B. Bullough, V. Bullough, M.A. Fithian, W.E. Hartman, & R.S. Klein (Eds.), Personal stories of “How I got into sex”: Leading researchers, sex therapists, educators, prostitutes, sex toy designers, sex surrogates, transsexuals, criminologists, clergy, and more…, pp. 75-86. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Press.

Denny, D. (Ed.). (1997c). Current concepts in transgender identity. New York: Garland.

Denny, D. (1999, 24 September). Beyond our slave names. Keynote address, Southern Comfort Conference, Atlanta, GA, 22-25 September, 1999.

Denny, D., & Bolin, A. (1997). And now for something completely different: An outcome study with surprising results and important implications. Paper presented at the XVth Symposium of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, Vancouver, Canada, 10-13 September, 1997.

Dolan, J.D. (1987). Transsexualism: Syndrome or symptom? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 32(8), 666-673.

Duberman, M.B. (1993). Stonewall. New York: Dutton.

Edgerton, M.T. (1974). The surgical treatment of male transsexuals. Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 1(2), 285-323.

Feinberg, L. (1996). Transgender warriors: Making history from Joan of Arc to Ru Paul. Boston: Beacon Press.

Fisk, N. (1973). Gender dysphoria syndrome (the how, what and why of a disease). In D. Laub & P. Gandy (Eds.), Proceedings of the Second Interdisciplinary Symposium on Gender Dysphoria Syndrome, pp. 7-14. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Medical Center.

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates.New York: Doubleday.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice‑Hall.

Green, J., Denny, D., & Cromwell, J. (In progress). Study on respectful language. Atlanta, GA: American Educational Gender Information Service, Inc. and San Francisco: FTM International.

Green, R. (1997). Conclusion to Transsexualism and sex reassignment: Reflections at 25 years. In D. Denny (Ed.), Current concepts in transgender identity. New York: Garland Publishers.

Green, R., & Money, J. (Eds.). (1969). Transsexualism and sex reassignment. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Greer, G. (1989, 22 July). Why sex-change is a lie: Or why men can never become women. The Independent Magazine, 16.

Hamburger, C., Sturup, G.K., & Dahl-Iversen, E. (1953). Transvestism: Hormonal, psychiatric, and surgical treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 12(6), 391-396.

Hershberger, S.L. (1997). Review of Ken Plummer (Ed.), Modern homosexualities: Fragments of lesbian and gay experience. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26(5), 559‑561.

Hirschfeld, M. (1910). Die transvestiten: Eine untersuchung uber den erotischen verkleidungstrieh. Berlin: Medicinisher Verlag Alfred Pulvermacher & Co.

Hoenig, J. (1974). The management of transsexualism. Canadian Psychiatric Association, 19(1), 1-6.

Hooker, E. (1957). The adjustment of the male overt homosexual. Journal of Projective Techniques, 21.

Imber, H. (1976). The management of transsexualism. Medical Journal of Australia, 2(18), 676-678.

Kessler, S.J., & McKenna, W. (1978). Gender: An ethnomethodological approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Reprinted in 1985 by The University of Chicago Press.

Krafft-Ebing, R. von. (1894). Psychopathia sexualis (C.G. Chaddock, Translator). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. Reprinted in 1931 in Brooklyn by Physicians & Surgeons Book Co.

Kuhn, T.S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press..

Laub, D.R., & Fisk, N. (1974). A rehabilitation program for gender dysphoria syndrome by surgical sex change. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 53(4), 388-403.

LaVigna, G.W., & Donellan, A.M. (1986). Alternatives to punishment: Solving behavior problems with non‑aversive strategies. New York: Irvington Publishers, Inc.

Levine, S.B. (1997). The revision of the Standards of Care for the Treatment of Gender Identity Disorders. Paper presented at the Second International Congress on Sex and Gender Issues, King of Prussia, PA, 19‑22 June, 1997. Available on audio cassette from Renaissance Education Association, 987 Old Eagle School Road, Ste. 719, Wayne, PA 19087.

Lothstein, L.M. (1979). Group therapy with gender-dysphoric patients. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 33(1), 67-81.

Lothstein, L.M. (1982). Sex reassignment surgery: Historical, bioethical, and theoretical issues. American Journal of Psychiatry, 139(4), 417-426.

Lothstein, L.M. (1983). Female-to-male transsexualism: Historical, clinical and theoretical issues. Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Lothstein, L.M. (1997). Pantyhose fetishism and self-cohesion: A paraphilic solution?: Response to Ken Corbett. Gender & Psychoanalysis, 2(2), 273-281.

MacKenzie, G.O. (1994). Transgender nation. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green University Popular Press.

McHugh, P.R. (1992). Psychiatric misadventures. American Scholar, 61(4), 497-510.

McCloskey, D.N. (1996, June). An economist’s new clothes. Lingua Franca, 67‑69.

Milliken, A.D. (1982). Homicidal transsexuals: Three cases. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 27(1), 43-46.

Money, J., & Primrose, C. (1968). Sexual dimorphism and dissociation in the psychology of male transsexuals. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 147(5), 472-486.

O’Donovan, O. (1982). Transsexualism and Christian marriage. Bromcote, Notts: Grove Books.

O’Donovan, O. (1984). Begotten or made? Oliver O’Donovan.

Pauly, I.B. (1992). Review of L. Sullivan, From female to male: The life of Jack Bee Garland. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 21(2), 201-204.

Person, L., & Ovesey, E. (1978). Transvestitism: New perspectives. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 6, 301-323.

Raymond, J. (1979). The transsexual empire: The making of the she-male. Boston: Beacon Press. Reissued in 1994 with a new introduction by Teacher’s College Press, New York.

Roback, H.B., McKee, F., Webb, W., Abramowitz, C.V., & Abramowitz, S.I. (1976). Psychopathology in female sex-change applicants and two help seeking controls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85(4), 430-432.

Socarides, C.W. (1976). Beyond sexual freedom: Clinical fallout. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 30(3), 385-397.

Socarides, C. (1996). The erosion of heterosexuality: Psychiatry falters, America sleeps. American Family Association World Wide Web Page, http://www.gocin.com/afa/home.htm. Reprinted from The Washington Times (date not given).

Spitzer, R. (Ed.). (1994). DSM-IV casebook: A learning companion to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.

Steiner, B.W. (1985). The management of patients with gender disorders. In B.W. Steiner (Ed.), Gender dysphoria: Development, research, management, pp. 325-350. New York: Plenum Press.

Steiner, B.W. (1990). Intake assessment of gender-dysphoric patients. In R. Blanchard & B.W. Steiner (Eds.), Clinical management of gender identity disorder in children and adults, 93-106. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.

Steiner, B.W., Zajac, A.S., & Mohr, J.W. (1974). A gender identity project: The organization of a multidisciplinary study. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal, 19(1), 7-12.

Stoller, R.J. (1982). Near miss: “Sex change” treatment and its evaluation. In M.R. Zales (Ed.), Eating, sleeping, and sexuality, pp. 258-283. New York: Brunner/Mazel. (84 refs.)

Stone, A.R. (As Sandy Stone) (1991). The empire strikes back: A posttranssexual manifesto. In J. Epstein & K. Straub (Eds.), Body guards: The cultural politics of gender ambiguity, pp. 280-304. New York: Routledge.

Stone, C.B. (1977). Psychiatric screening for transsexual surgery. Psychosomatics, 18(1), 25-27.

Sullivan, L. (1989, 6 June). Sullivan’s travels. The Advocate, Issue 526, 68-71.

Taylor, T. (1996). The prehistory of sex: Four million years of human sexual culture. New York: Bantam Books.

Ulrichs, K.H. (Michael A. Lombardi-Nash, translator). (1994). The riddle of “man-manly” love: The pioneering work on male homosexuality, Vols. 1 and 2. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Press.

Walker, P.A., Berger, J.C., Green, R., Laub, D., Reynolds, C., & Wollman, L. (1984). Standards of care: The hormonal and surgical sex reassignment of gender dysphoric persons. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 13(6), 476‑481.

What’s Wrong with Stanford? (ca 1980). San Francisco: Golden Gate Girls/Guys.

Wiedeman, G.H. (1953). Letter to the editor. Journal of the American Medical Association, 152(12), 1167.

Wilson, K.K. (1997). Gender as illness: Issues of psychiatric classification. Paper presented at the 8th Annual International Conference on Transgender Law and Employment Policy, Houston, Texas, 11-12 July, 1997.

Wilchins, R.A. (1997). Read my lips: Sexual subversion and the end of gender. Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books.

Zucker, K. J., & Bradley, S. J. (1995). Gender identity disorder and psychosexual problems in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press.