Sex and Gender Characteristics: How Men and Women Differ (1990)

©1990, 2013 by Dallas Denny

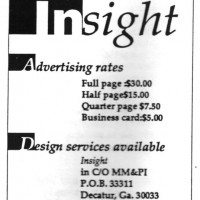

Source: Denny, Dallas. (1990, Fall). Sexual and gender characteristics: How men and women differ. Insight, 7-8 .

Sex and Gender Characteristics

How Men and Women Differ

By Dallas Denny

The statistically average genetic male differs from the statistically average genetic female In many ways, some of them striking, and some of them quite subtle. While the purpose of this article is not to provide a complete lesson in the morphology or psychology of sex differences, I do want to point out some of the obvious differences for purposes of illustrating some of the physical and behavioral problems transsexual persons must overcome. Most of the traits I mention are discussed by Desmond Morris in his books Manwatching and Bodywatching.

The average person is well aware that there are anatomical and behavioral differences in men and women, but when pressed may be unable to objectively describe any but the more obvious differences. It is the gestalt—the summation of characteristics—that causes us to identify a person as a male or a female. It is perfectly possible, of course, for a female to have one or several of the traits usually associated with the male (for example, great height and a deep voice), without her sex or gender being questioned. Conversely, a male can be small-boned and without appreciable facial hair, and yet escape being mistaken for a female. It is only when a combination of characteristics begins to tip the scale that we see the person as a member of the opposite sex.

What are these differences? They are manifold. First, there are gross differences in morphology. Anatomists can tell the skeletons of males from those of females, and internal organs differ as well. Genetic males tend to be taller, with larger hands and feet, heavier bones, broader shoulders, and hips which are narrower than those of genetic females. Their brow bones are more pronounced, and they tend to be more prognathous (have heavier jawbones) than do females. The male pelvis makes for more efficient walking and running than does the female’s, which is compromised by the conflicting requirements of locomotion and childbearing. The male is stronger, with more pronounced muscles. His legs and arms are proportionally longer, and his forearm is longer in relation to his upper arm than is the female’s. His hands are bigger, with thicker fingers and stronger thumbs. His chest is bigger, to house bigger lungs. His neck is shorter and thicker. His brows are bushier; her eyes are proportionately larger. His nose is more prominent. And of course, his reproductive organs are on the outside of his body, whereas the female’s are inside.

The female has larger, fleshier lips, and her buttocks protrude more than does the male’s because of her pelvic anatomy. She has more fat on her body, and it is distributed differently. She is fleshier in the shoulders and knees, and in the breasts, buttocks, and thighs.

Fat in the male tends to show up as a pot belly. In the female, fat tends to show up the thighs, buttocks, and upper arms.

The secondary sex characteristics of males and females arise at puberty, triggered by gonadotropins (the sex hormones— estrogens and androgens) The males voice deepens, and he may develop a visible Adam’s apple. Facial hair, and genital and axial (armpit) hair appear; thick body hair appears on the arms, legs, chest, and stomach—and sometimes the back and neck. If he carries gene for pattern baldness, a man will begin to rapidly lose his hair, and even if he doesn’t, androgens will often cause the hair to thin. His skin will become oilier.

The female’s voice also deepens, but not as much. She develops genital and axillary hair and body hair as well, but generally not to the extent of the male. Her genital patch will differ from that of the male, being triangular in shape, whereas his extends upwards toward the navel. Her breasts grow and her hips widen.

Many of the physical differences in males and females occur at puberty as the result of mediation by gonadotropins. Administration of opposite-sex hormones after puberty can offset some of these differences— for instance, causing breast development and redistribution of body fat in genetic males, and causing deepening of the voice and beard growth in genetic females— but other changes, once triggered, are not subject to hormonal reversal. A six-foot-two male will not shrink to the five-foot-seven height that may have been his ceiling if he had received estrogens at puberty, and a five-foot-two-inch female will not grow to the five-foot-ten height she may have achieved with androgens at puberty (although she may grow an inch or two). Neither will large hands and feet or broad shoulders go away, or will pattern baldness reverse itself— and the male’s voice will not raise in pitch.

Behavioral differences are legion, and to a large degree unstudied. Males tend to be louder and more boisterous than females, and are often more object-oriented and less aware of or attach less importance to interpersonal relationships than do women. Their movements are more rapid and less streamlined and smooth than those of women. Their speech differs from that of women. They are quicker to show anger and slower to express tenderness.

Many behavioral differences are subtle; when passing a male n a crowd, women tend to turn away from him; the male usually turns toward her. Women clasp their hands more often. Women are more likely than women to fold their arms across their chests (and the way in which they fold their arms and cross their legs is topographically different than in men. Desmond Morris points out in Manwatching that males often mimic this behavior in an exaggerated manner when pretending to be feminine.

Other gender signals are what Morris calls invented; that is, they arise for cultural reasons. They are not inherently masculine or feminine, but are interpreted as such because of the society in which they occur. Morris’ examples of invented signals are “short hair versus long hair; skirts versus trousers; handbags versus pockets; makeup or no makeup; and pipes versus cigarettes.” Invented gender signals can influence behavior—long hair can be tossed or stroked in ways short hair cannot. Skirts demand a modest way of sitting, and this habit can persist even when an individual is wearing trousers. Invented signals cross the line from sex to gender; they are part of the learned display that makes us a man or a woman, and have little to do with being male or female.

Sex reassignment requires tipping the balance—altering the sexual characteristics so that one is perceived as and believed to be of the sex that corresponds with the gender of choice. Some characteristics (height, bone structure, pitch of the voice) are unfortunately set at puberty, and little can be done about them. Others (breast development, body hair, fat distribution, and, for the FTM, facial hair and vocal pitch) can be altered over time by administration of male or female gonadotropins. Other traits can be altered surgically; unwanted hair removed by electrolysis, genitals refashioned by surgery, faces or breasts or Adam’s apples reshaped by the scalpel of the plastic surgeon; hair transplanted. Desired behavioral patterns can be learned through observation of others and by practice and self-monitoring, and undesired behavioral patterns can be eliminated in the same way.

Despite the myriad differences between the sexes, is it possible to change one’s body; it is possible to come to look like, sound like and live as the opposite sex. Surgery, hormonal therapy, and hard work—over time—can do it. One must, of course, take a hard look at what one has to work with: a five-foot-and-two-inch tall women will be a five-foot-and-two-inch man. A man with size thirteen feet will be a woman with size thirteen feet. But most men and women can come to tip the balance so they are perceived as the gender of choice.