The Standards of Care: What Are They? (1990)

©1990, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Sources

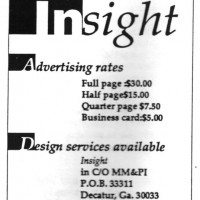

Denny, Dallas. (1990, Fall). The Standards of Care: What are they? Insight, 8.

Denny, Dallas. (1993, February). The Standards of Care: What are they: T.A.T.S. Newsletter, February, 1993, pp. 2-3.

The Standards of Care

What Are They?

By Dallas Denny

Most transsexual persons, and probably most physicians and psychologists, don’t realize there is a set of minimum guidelines for hormonal and surgical treatment of transsexual people. These guidelines were developed in 1979 and were last revised in 1981. They are called the Standards of Care.

The Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, Inc. (HBIGDA) is comprised of physicians and clinical behavioral scientists (psychologists and other mental health professionals) who provide diagnosis and therapy for transsexual people. Concerned by a lack of standardization of treatment, HBIGDA’s Standards Committee developed the Standards of Care to provide protection for both service providers and transsexual persons. Before the Standards were published, requirements varied according to the beliefs or value systems of the clinics or persons providing services. Some had very harsh requirements and some had almost none—hormonal and surgical reassignment on demand, as it were.

The Standards of Care brought some order out of chaos. For the first time there was some quality assurance for treatment of transsexual persons. As with most standards, however there is some latitude for interpretation, and modern-day service providers may still have varying requirements—but the variation is much less than that which existed before the Standards. It should be noted the Standards are minimal rather than optimal, and can, and in the opinion of the Standards Committee, often should be exceeded.

Many transsexual people consider the Standards of Care a series of hurdles they must leap. In a sense, they are. They require the individual to seek services—like psychotherapy—(s)he may or may not feel (s)he needs, and these services are often expensive. They may delay hormonal or surgical reassignment—indefinitely, in some cases, if the individual doesn’t meet the diagnostic criteria for gender dysphoria. Many transsexual people want and even demand hormonal and surgical sex reassignment surgery on demand. They feel, with reason, that their bodies are their own to do with as they please. Physicians feel, with reason, that hormones and surgery may be counterindicated in some instances. Understandably, these different feelings make for some friction between the transsexual and medical communities—and doubtless between many transsexual people and their individual physicians and therapists.

The Standards minimize the chance of permanently making irreversible changes to the body. For example, surgical reassignment procedures are allowed only late in the game, after the transsexual person has successfully lived in the gender of choice (is somatically gender-consonant) and is unlikely to revert to the original gender.

The first step for the transsexual person is to obtain the services of a clinical behavioral scientist (therapist). The therapist, who can be a psychiatrist, psychologist, clinical social worker, family and marital therapist, licensed professional counselor, or pastoral counselor, will give a diagnosis. If the diagnosis is gender dysphoria (transsexualism), the therapist will write a letter indicating so. The transsexual person will take this letter to an endocrinologist, who will prescribe hormones. After an indeterminate time on the hormones, and after electrolysis for the male-to-female, the transsexual person will enter a period of real-life test, living in the gender of choice. Reassignment surgery is done only after one to two years of RLT and with letters from two therapists. The transsexual person must maintain an ongoing relationship with at least one of the clinicians; in this way the therapist can verify the desire for gender change is ongoing and not of recent origin.

Most transsexual people can negotiate the hurdles imposed by the Standards of Care. Despite the criticisms of the Standards by some factions of the gender community, and despite their inadequacies, they were a major step forward. Before there was uncertainty; now there is a clearly defined series of steps (or hurdles, if you will).