Interview with David Ebershoff (2000)

©2000, 2013 by Dallas Denny

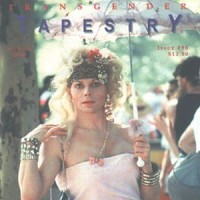

Source: Denny, Dallas. (2000, Summer). Interview with David Ebershoff. Transgender Tapestry, 90, pp. 60-64.

Source: Ebershoff, David. (1999). The Danish girl. New York: Viking. 280 pp. ISBN 0-670-88808-7

Ebershoff, the publishing director at Modern Library, has taken a highly unusual subject— and a big chance— for his first novel. That it comes off triumphantly is a tribute to his taste and restraint and to the highly empathetic quality of his imagination. His book is based on the real-life story of Einar Wegener, a Danish artist who 70 years ago became the first man to be medically transformed into a woman— long before the much better-known case of Christine Jorgensen. Ebershoff has naturally changed some of the characters, giving Einar an American wife from his own native city of Pasadena, thereby introducing a New World perspective to the drama.

— Publisher’s Weekly, 22 November, 1999

Review by Dallas Denny

Those who have read Niels Hoyer’s Man into Woman will know it as the story of Einar Wegener, a Danish painter who underwent several surgical procedures back in the 1930s in order to become Lili Elbe, his alter ego. I can’t speak to the original Danish, but the English translation is hauntingly written as Hoyer almost poetically describes Einar’s gradual self-realization that he is a woman and the steps he and his wife Gerda take to make Lili a reality.

It’s a remarkable tale, one deserving of wide recognition, but Lili’s story, although news in the 1930s, had been largely forgotten— that is, until David Ebershoff wrote The Danish Girl, a novel based on Lili and Gerda’s experiences.

I received the advance publicity for The Danish Girl before the book itself arrived, and I must confess, I was prepared to dislike it. Perhaps because I liked Man into Woman so very much, and perhaps because I am frustrated by the common relegation of females into the background in tales of male-to-female transpersons, I was offended that Ebershoff had changed Einar’s Danish wife Gerda into Greta, an American. How dare this man toy with the woman who had loved Einar and supported him in his quest of becoming!

And yet, when the book arrived and I began to read, I couldn’t maintain my indignation. Yes, Ebershoff had transformed Gerta into Greta, but Greta was no one-dimensional supporting character thrown into the book as a convenient foil for Einar’s transformation. Rather, she was a strong and independent woman, and it was clear The Danish Girl was as much, and perhaps more, about her than it was about Einar and Lili. By the end of the first several chapters I was able to put my prejudices aside and read for enjoyment.

And enjoy I did. The Danish Girl, like Man into Woman is a beautiful book.

Interview with David Ebershoff

David Ebershoff is the author of the remarkable new novel The Danish Girl. Your editor interviewed him via the internet.

Tapestry: How did you discover the story of Einar and Gerda Wegener?

Ebershoff: A few years ago I began flipping through a book a friend had sent me. Buried in its pages, parenthetically, in fact, was a short paragraph about Einar Wegener. I had always thought Christine Jorgensen, an American GI from Brooklyn, had been the first man to surgically change to woman. Something in this tangential paragraph made me curious. Why was this person forgotten from history? Who was he? Who was his wife? How did such a transformation affect their marriage?

Tapestry: When you first came across that reference to Lili Elbe, the one that intrigued you, and began to follow up on it, I would expect you straightaway came across Niels Hoyer’s evocative biography, Man into Woman. Was that the first thing you found? What other materials did you locate, and how did you find them? How much did they tell you about the lives of Gerda and Einar Wegener and Lili Elbe?

Ebershoff: Man into Woman— Lili Elbe’s diaries and correspondence, which Niels Hoyer edited— was not the first book I came across while researching The Danish Girl, although certainly it turned out to be the most important source for my research. The novel is without a doubt indebted to it. The other important sources that were important were the newspaper accounts of Wegener’s transformation into Lili. This was a big story in 1930 and 1931, and it was reported widely in Europe and to a lesser degree in America. I also found limited information about Wegener in other books written about transgendered men and women, as well as in medical books that deal with sexual topics. But these sources tended to focus on the clinical details of Einar Wegener and Lili Elbe: the three surgeries at the Dresden Municipal Women’s Clinic; the mysterious bleeding that preceded the surgeries; Einar’s pair of underdeveloped ovaries buried in his abdomen. Not much could provide me with rich detail about the way Einar and his wife and Lili Elbe lived their lives. That’s why I had to go to Europe to write this book.

Tapestry: How many times did you visit Europe while researching the novel?

Ebershoff: I made three trips. First I visited Copenhagen, where I researched at the Royal Library. There I saw an original Danish edition of the diaries, and read on microfiche (with the help of a translator) the accounts of Einar and Lili’s story as recounted in the Danish press. One newspaper in particular, Politiken, covered the story extensively and very sympathetically. Those articles— a few of them full of detail and penned by Lili Elbe but published under a pseudonym— were very important sources for The Danish Girl. These press accounts, published in 1931, were the first time the world could read about what happened to Einar Wegener and who Lili Elbe was. They describe Einar’s gradual self-realization, the many futile visits to various ill-informed doctors, and Einar’s eventual journey to the Dresden Municipal Women’s Clinic. Part of what is described in Man into Woman first ran in Politiken.

While in Copenhagen I also visited the Royal Academy of Arts, where both Einar and Gerda Wegener were students. In my novel Wegener’s wife is Greta, but in actuality her name was Gerda. The Academy maintains a library on Danish artists, and this is where I first read of Gerda’s successful career, and the extent to which her paintings of Lili Elbe brought her acclaim. In the library’s files I first saw some of the many images of Gerda Wegener’s paintings, as well as read more details of her life: how she would have her husband paint the backgrounds of her paintings; about her successful career in Paris illustrating for fashion magazines such as Vogue; about her highly modern artistic style, which was in contrast to the 19th century style of Einar Wegener. This same trip to Copenhagen I retraced Einar and Gerda’s footsteps, visiting the neighborhood of Nyhavns Kanal where they lived and the park, Kongens Have, where they would stroll late on mid-summer nights. I hunted the Copenhagen flea market for old maps and picture books portraying images of the streets of Copenhagen and the Danish bogs in the early part of the 20th century.

My research took me back to Europe two other times. In Dresden a boxy cement building houses the Dresden Hygiene Museum, a creaky institution poorly funded, but perpetuated by the Communists. Now it sits dusty, waiting for the few visitors it receives each day. Its small library provided me with further details of Wegener’s transformation and of material life in Dresden in 1930 and 1931: the elegant arc of the Elbe River; the limestone facades of city now destroyed; the cast of gloom as Germany lurched into its darkest time.

Another trip took me to Paris, where I visited the medical clinics at which Einar and Greta first sought help. That same trip I returned to Copenhagen for further information about Einar and Greta and to see some of their artwork, especially the candy-bright paintings painted by Greta of her husband dressed as Lili. One of those paintings is on the spine and back jacket of the American edition of the novel.

Tapestry: Did you have a chance to see any of Einar or Gerda’s original paintings?

Ebershoff: Yes. A museum in Copenhagen has had an exhibition of about 70 of Gerda Wegener’s paintings up for several months. Through my research I got to know the head of the museum, and he showed me several of the paintings he was curating for the show. Many of the paintings are in private hands, but some of their owners have showed me their paintings, some of which have been out of public view since they were originally executed.

Tapestry: Man into Woman is illustrated with several of Gerda Wegener’s Lili paintings. In real life, did Gerda paint Lili as extensively as did Greta in your book?

Ebershoff: She did dozens of paintings of Lili, as well as many sketches. But in real life her career didn’t rest entirely on her Lili paintings. She was also a prolific illustrator for the fashion magazines of Paris, as well as a high-end pornographer. Her art is Art Deco in style, very modern, and had been out of fashion until the last ten years. Currently, there is a great demand for her paintings in Europe, and they have sold for as much as $250,000.

Tapestry: You mention in your Afterword that of necessity you made up some of the particulars of the novel. Could you give an example or two about what in the book the reader might think is fiction but is real and what the reader might think is real but is fiction?

Ebershoff: The novel, by its very definition, is an invention of my imagination. I decided to write this story as fiction because I wanted to retell it in a way that evoked the complicated emotions of both Einar and Gerda Wegener. One detail in the book that might seem fictional but is actually true is Einar’s mysterious bleeding. For several years prior to his surgeries, he did in fact suffer from a periodic bleeding from his nose and anus. It wasn’t monthly, but almost, and Einar came to believe in this hemorrhaging as a sort of symbolic menstruation. In fact it was the result of the pair of rudimentary ovaries in his abdomen, which his doctor in Dresden discovered. This fact seems like the detail a writer of magical realism might invent, but it’s true.

Something in the novel that might seem true but is invented is the character of Hans. In reality, Wegener had no boyhood friend with whom he was uncommonly close and who became an important figure in his adult life. But I wanted to create a past for Einar which could help give context to his present situation.

Tapestry: Did Gerda and Lili actually live for a time in Paris?

Ebershoff: Yes, not in the Marais, but on the left bank, off St-Germain-des-Pres. Paris was a freeing environment for Einar and Lili, and especially freeing for Gerda and her art. She had an easier time as a female artist in Paris than in Copenhagen.

Tapestry: In real life, did Gerda have a relationship after Einar became Lili but before her death? What about in Gerda’s later life? Did she remarry?

Ebershoff: Yes, Gerda actually remarried before Lili died. She married an Italian army officer and moved to the north of Italy. Gerda lived for about seven or eight years longer than Lili, dying in the late 1930s, just before the outbreak of World War II.

Tapestry: In actuality, did Lili leave the clinic and function in society for a time between the second and third operations?

Ebershoff: Lili’s first operations were in 1930, and after her recovery she returned to Copenhagen and had about 6 or 9 months of life as a young woman in Denmark before she returned to Dresden for her final operation, the one that arguably killed her. She didn’t ever fully function in society, however, because when word got out about her story she was hounded by the world media, and she had to go into a sort of hiding. She never took a job, as Lili does in my novel. But I didn’t want to write about the media frenzy because, to me, that is very uninteresting and generally reduces a person to a caricature of themselves. I wanted to write about the few months when Lili might have felt most accepted and self-accepting.

Tapestry: Did Lili had relationships with men?

Ebershoff: She fell in love with a man in the last year of her life, a man who asked her to marry him. However, I do not know if that love was ever consummated. Something makes me suspect it was not, in part because her surgeries were so crude that she was constantly in pain after them. But perhaps.

Tapestry: What do you think caused her death? A rejected uterus transplant, as in your book?

Ebershoff: The first operations, in 1930, left Lili with terrible pain, which she bore bravely. When she returned to Dresden in 1931 for a final operation, she was already fairly weak. There is some speculation about what the final operation was. I have read that it was to construct a vagina. But I have also read a few things that led me to believe that the doctor’s final operation was more drastic, like the transplant of a uterus. This doctor was skilled at transplants and interested in experimenting with them; he had also promised Lili that he could make her fertile. Based on this I’ve speculated that he attempted a uterine transplant— an operation that can go horribly wrong. But my speculation cannot be taken as fact.

Tapestry: When you were in Dresden did you perchance attempt to seek out Lili’s grave? If so, was it still there? I ask this more for myself than for our readers. I used the picture of her tombstone from Man into Woman as the frontispiece for one of my books. I expect that because of the fierce Allied firebombing it’s been gone these 50 or so years, but I’d very much like to know for sure.

Ebershoff: I went to Dresden for four or five days in April, 1998, and attempted to find her grave, but could not. The clinic doesn’t exist as it did in the 1930s, and the city itself has, of course, fundamentally changed. An important thing to remember about a mass destruction like the Dresden fire-bombing is that not only was the city leveled, but most of its records— the letters, files, and clippings that provide details of the millions of lives lived there— burned on those horrible nights in the spring of 1945.

Tapestry: Your concluding paragraphs are quite ambiguous. They leave Lili, deathly ill, in a wheelchair in Dresden, abandoned temporarily by Carlisle and Anna. What do you suppose the reader will assume here? That Lili will recover? That she will die? Why did you choose to end this way?

Ebershoff: You’re absolutely right. The novel ends ambiguously. Readers have told me they find the ending sad, while others have told me it is hopeful. There is no correct interpretation. I wrote it ambiguously because I feel it’s more subtle, and that subtlety was very important to writing this novel. The novels I like to read generally have endings that open up the story as much as close them; I like it when a writer allows the reader to make some conclusions for him or herself, and that is why the novel concludes this way.

Tapestry: Niels Hoyer makes it quite clear in Man into Woman that Einar and Lili were separate and distinct. He remarks, for example, about the dramatic difference between Einar’s pre-surgical handwriting and Lili’s postoperative handwriting. Do you think Einar and Lili were such different personalities in real life as they are in the book? Do you suppose that’s true of transsexual people today?

Ebershoff: I wrote The Danish Girl to explore the subtlety of a transgendered person’s experience. I believe Einar and Lili were not two distinct people — that would imply that there was no evolution from one to the other. This is indeed different from how Einar and Lili are portrayed in Man into Woman. My novel, of course, is not meant to represent the experiences of all transgendered people, just one transgendered person, who happened to be the first. My job as a novelist was to describe and detail as deftly as I could one person’s life, not the lives of a whole set of people in society. Therefore, I cannot say whether or not transsexual people today have totally distinct lives from that of who they were before their surgeries. However, I believe generally things aren’t that black and white; that transgendered people, like everyone else, are made up of subtle shadings of experience and history; that what happened to us as children will, no matter what, impact who we are as adults, even if one has changed his or her gender.

Tapestry: Often, in writings about MTF transgendered people, natal females are relegated to supportive positions, their power removed, made invisible. When I read in your promotional material that you had changed Gerda’s name and made her an American, I assumed the worst— but Greta was someone I could relate to, someone with a strong personality, a real person, much more colorful than either Einar or Lili. The Danish Girl is Greta’s story as much— more, even— than Lili’s. Did you intend this from the beginning, or did the character just develop that way?

Ebershoff: Again, you’re right. Greta is in many ways the outsized character of the novel, and in some ways this book is her story. Developing her character took a couple of years writing and rewriting, filling in the details, so I was not exactly sure just how strong, how fascinating she was when I began to write the book. But over and over I kept asking myself what kind of woman would do this for her husband? What kind of woman could understand her husband so thoroughly, perhaps even better than he understood himself? I wanted to write the book as a love story, the exploration of a marriage that undergoes a fundamental change. The novel asks the question that everyone has at least once faced: what do you do when the person you love changes? It’s a defining question for all relationships, but especially when one half of the couple is a transgendered person.

Tapestry: And finally (bet you’re glad!): I’ve heard there’s a bidding war for the screen rights. Do you think we’ll see Lili and Greta one day soon in a motion picture?

Ebershoff: There have been offers for the movie rights, but as of right now I’ve not struck a deal. A movie version of The Danish Girl would require a director with a subtle vision and an ability to create a world on the screen where the characters are real and intelligent and humanly flawed. I care deeply about Einar Wegener, Lili Elbe, and Greta Waud, and I hope the film version of their lives can portray them as the brave, passionate, and complex people they were.