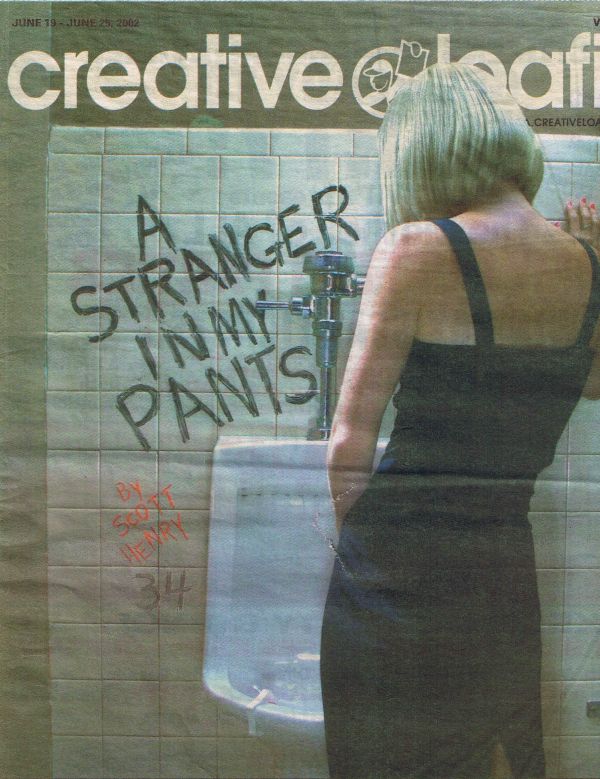

A Stranger in My Pants (2002)

©2002 by Scott Henry

Source: Henry, Scott. (2002, 19 June). A stranger in my pants. Creative Loafing, cover, 34-39.

Atlanta’s Creative Loafing is an unlikely place for a semi-serious article about transsexualism. Scott Henry thought he was being clever. He’s wasn’t.

A Stranger in My Pants

A Man Near You is Having His Own Vagina Monologue. Is Trannie Chic Far Behind?

By Scott Henry

Consider for a moment that freak of nature we call the platypus. Four‑footed, warm-blooded, fur-covered, it’s a critter that, despite its webbed feet and duck’s bill, seems as if it could safely be categorized as mammalian.

Yet it’s here that the platypus lays an egg, literally. By failing the litmus test for membership into mammaldom—bearing live young—the creature threatens to wreak zoological chaos. It certainly wouldn’t fly as a bird, but is it truly a mammal? Moreover, why should we care about any of this when the platypus itself is utterly unconcerned?

Setting aside our metaphor-rich mascot for the time being, let’s meet Jessica Eberle, a software programmer who rides a motorcycle, plays drums and just began learning the bass guitar. She wears little makeup, doesn’t like frilly dresses and walks around barefoot in the modest northwest Atlanta bungalow she recently bought and shares with her girlfriend of two years. Bisexual, but leaning toward lesbian, she confides that the two have gotten involved in the local S&M community.

Setting aside our metaphor-rich mascot for the time being, let’s meet Jessica Eberle, a software programmer who rides a motorcycle, plays drums and just began learning the bass guitar. She wears little makeup, doesn’t like frilly dresses and walks around barefoot in the modest northwest Atlanta bungalow she recently bought and shares with her girlfriend of two years. Bisexual, but leaning toward lesbian, she confides that the two have gotten involved in the local S&M community.

Fact is, there’s really only one personal detail that the amiable Jessica seems reluctant to discuss. It’s like pulling teeth to get her—as she covers her face in embarrassment—to divulge the name her parents gave her 33 years ago. That would be Jeff. Not a bad name, but, obviously, not one that most women find themselves saddled with at birth.

Jessica, however, isn’t most women. By Texas State Supreme Court standards, she’s not really a woman at all, but more about that in a moment. Then again, she certainly isn’t a man — and hasn’t been one for some time now.

Her “transition,” as it’s called in the transgender community, took place a decade ago and involved two years of hormone treatments and full sex-reassignment surgery. For a long time afterward, Jessica would become infuriated when people still would call her “sir.” Were these clods so dense they couldn’t tell someone so determinedly feminine was a “she” not a “he?” Then came her epiphany.

“Once I realized I didn’t have to be one or the other, but could be somewhere in between better,” she explains.

It’s safe to say that there now are more such in-betweeners than at any time in human history. Certainly more than in 1952, when an obscure ex-G.I. left for Denmark as George Jorgensen and returned an overnight celebrity as Christine. More than in 1977, when tennis player Renée Richards won in the courts of New York the right to return as a woman to the courts of the U.S. Open, where she once had competed as a man.

And, although there are no such well-known female-to-male role models, the ranks of what had long been a stealth group are growing and becoming more vocal.

The role the Internet has played in informing, connecting and sometimes mobilizing the transgender community cannot be overstated. Only a generation ago, people routinely grew up feeling completely isolated and alone in their doubts; now they can choose from a collection of online trannie diaries to see how others have coped with their problems.

Today, transgender advocates are working to overturn not only rigid gender stereotypes, but the fundamental assumption—understood and accepted intuitively by any child— that there are only two sexes, and if you’re not one, then you’ve got to be the other. Instead of just chocolate or vanilla, there’s an entire rainbow of flavors, they argue. Political correctness aside, they may be winning this battle.

It’s something of a cliche, Jessica concedes, but her pre-platypussian childhood in south Florida was overshadowed by the horrific certainty that she was the victim of some terrible genetic accident, a chromosomal gender-bender.

“I always wanted to do what the girls were doing— playing with Barbie instead of G.I. Joe— but I was doing boy stuff and I didn’t know why” she says. “It was like I was living the first 21 years of my life as someone else.”

Specifically, she was going through the motions of growing up as the boy she knew deep inside that she wasn’t, despite the way everyone treated her and the evidence offered by her own male anatomy. Needless to say, this was knowledge she could barely admit to herself, much less share with others. As the unhappy, adopted son of a middle-class couple, Jessica reacted to cruel puberty by embracing the expectations placed upon teenage boys, hoping to shake something loose in her psyche. Tall, trim, and athletic, Jessica played football and became captain of the high school wrestling team. Privately, she loathed both sports.

“I cried once after a wrestling match and everyone assumed it was because I lost, but it’s because I couldn’t understand why I should want to hurt people,” she recalls.

Relating as naturally to girls as she did made it easy for the sensitive youngster to make female friends—and to get those friends into bed. She cut a wide swath through the eligible maidens at her school, partly to reassure the conflicted Jeff’s sense of masculinity.

“I’ve always had lesbian relationships,” Jessica says, smiling. “My partners just didn’t know it at the time. She laughs now, but back then, he was miserable. And if this game of musical pronouns is hard to follow in print, imagine how confusing it must be to live as an 18-year-old boy uncomfortable in her own skin. After a few weeks of much-needed psychotherapy, Jessica realized that in order to find any happiness in life, she would have to emerge as the woman she always believed himself to be.

She had been working for nearly a year at the Hard Rock Cafe in Orlando when she began the estrogen treatments that soon would induce her body to grow A-cup breasts, cause her muscles to soften and make her feel “ditzy and moody, like a 13-year-old girl.” It was time to tell her managers that Jeff the busboy would be leaving shortly and Jessica the busgirl would be taking his place.

“I think they kept me on because they knew they’d never win a lawsuit,” she says, “but they made me announce my my plans publicly at a staff meeting and asked me not to use the women’s restroom.” She began wearing makeup and women’s clothes on the job, stuffing her bra in anticipation of her transformation and holding her bladder all day rather than step up to a urinal dressed like that. Eventually I said, ‘To hell with it,’ started using the women’s restroom and no one ever said a word,” she recalls.

Along the way, there was the unenviable task of telling a couple of shocked parents that the trust fund they’d set aside to send their son to a good college would instead be used to send him to a good doctor, for a sex change.

“I told them I was willing to lose everything—friends, job, family— to make this happen, but they told me I could count on their support,” she says.

Jessica describes her two years as a pre-op transsexual as limbo. Dressed as a woman, but still equipped with male hardware that was becoming ever less, um, functional under the effect of female hormones, she begrudgingly complied with the real-life test.

In the late ’50s, American gender research pioneer Dr. Harry Benjamin introduced standards of care that have since been used almost universally to treat what the good doctor called gender dysphoria, or having a sexual identity that doesn’t match one’s genitals.

Under the Benjamin Standards, a candidate for sex-reassignment surgery can be prescribed hormones only after being diagnosed as a transsexual by a qualified gender therapist. Male patients should undergo electrolysis to combat their five-o’clock shadow. They must live 24/7 as a woman for at least one year and possibly two, until the therapist believes they are psychologically committed to surgery.

This test period is intended to separate true trannies, who will never be happy with their original parts, from mere cross-dressing fetishists and lifestyle dabblers who can’t really decide what they want. For her own surgery, Jessica shopped around and settled on a clinic in Montreal, where she could get retrofitted for around $7,000, about half the cost of her runner-up choice in Colorado.

The price is a huge consideration for all but the well-heeled; there’s not a health-insurance plan in the world that pays out to turn men into women (as anyone who’s seen Dog Day Afternoon already knows).

Folks who are squeamish should skip the next couple of paragraphs as we walk gingerly through a quick description of the procedure, after which you’ll agree that anyone who goes through with this isn’t just kidding around.

In the first of several steps that even Vlad the Impaler might describe as icky, the penis is split open, hollowed out (like a hot dog, according to one trannie) and the remaining skin is turned outside in. The erectile tissue (the filler, as it were) goes in the Dumpster and the foreskin is peeled off and set aside for later.

Still with us? OK, then. Next, the testes are 86’ed, but the scrotal sack is left attached. The surgeon hollows out a cavity between the legs and folds the ex-penile skin inside to form the walls of this new vagina. It’s here that you learn size really does count: The better hung the patient was, the deeper her well of womanhood will be.

Of course, the urethra is rerouted as the patient sacrifices one of the primary benefits of being male: the ability to pee standing up. Then, the scrotal skin is scraped free of pube follicles and sewn into place as the vulva. As the crowning touch, the foreskin is sculpted into a clitoris and grafted onto the new creation. And voila!

Or, aaiiieeee!, depending on your point of view.

“Nobody told me there could be that much pain,” recalls Jessica, wincing. After surgery, she moved in with her parents for a while to recuperate and plan her life as a woman: She would go to a state college, get a tech job and return to dating, not necessarily in that order.

“When I recovered, there are were three things I wanted to do with my vagina: have sex with myself, have sex with a woman and have sex with a man, to see what it felt like,” she says.

According to Jessica, sex is better as a woman than it ever was as a man, both psychologically and physically. She claims she’s discovered another dividend of being female: multiple orgasms.

Of course, the desire to change one’s sex isn’t really about sex, in the carnal sense. Gender identity is the most deeply rooted sense of self that we possess, outranking and even altering sexual orientation.

Considering that perhaps half of transsexuals find themselves attracted to a different sex after surgery than they did before, sexual orientation can seem surprisingly flexible, according to Erin Swenson, a gender counselor with experience on both sides of the issue.

‘There’s something about living in the role of the other gender that changes things,” says Swenson, who transitioned convincingly from man to woman eight years ago. “Sexual orientation is not as fixed as we’d like to think it is.”

In many cases, a trannie’s rigid sense of gender-role equilibrium can seem to dictate that he/she remains “straight.”

Take John Weiss, for example, who’d gone through three wives—”Two of them I divorced and the third up and died on me”—fathered 10 children and spent 30 years driving an 18-wheeler.

Take John Weiss, for example, who’d gone through three wives—”Two of them I divorced and the third up and died on me”—fathered 10 children and spent 30 years driving an 18-wheeler.

All the while, he hid the passion for wearing women’s clothing that had gripped him since the age of five. After his parents caught him in a skirt as a youngster, John became a truck driver so he could spend more time away from home, making the long haul in pumps and hose because it “felt right and normal.” His wives left him because he was always on the road, but he’d never considered himself to be anything other than a straight guy who wore dresses on the sly; he had a family largely because that’s what guys his age did.

After the kids were grown and his third wife buried, he moved from Albuquerque to Atlanta and met other cross-dressers, but felt more kinship with the handful of transsexuals. Only then did the thought occur to him: “I should have been born a woman.”

Sidestepping the trial-period test against Swenson’s advice, in 1996 John flew to Brussels, where, for $6,000, a doctor agreed to transform him into Joan. That’s not all that changed.

“When I went over there, I liked girls,” Joan says. “When I came back, I liked guys. Now I’m female and I need to be with a man. I look at other women mainly to see what they’re wearing.”

Although Joan has had her Adam’s apple shaved down to aid the illusion, she still speaks in John’s unmistakably male voice and she concedes she couldn’t fool the eye in a medium-close inspection, in which she appears to be a somewhat weathered 58-year-old man of medium build with long hair and painted nails.

To their credit, Joan and Erin don’t go for the caked-on makeup, teased hair and Laura Ashley dresses that many middle-aged trannies seem to mistakenly believe will somehow camouflage their broad shoulders and big-boned physiques.

Joan gave every scrap of her man’s clothing to Goodwill, but still prefers to wear jeans and T-shirts around the Acworth home she shares with her partner, a 50-ish industrial mechanic.

She jokingly calls their relationship a case of mind over matter: “If he doesn’t mind, it doesn’t matter. Basically, the novelty is gone and now I’m a housewife.”

Retired from truck-driving, Joan does housework, raises two shar-peis, chats with neighbors about typical female stuff and enjoys talking to her children, at least the ones who’ve been able to handle their father’s transformation into Donna Reed.

Joan claims she has never for a moment regretted her latent sex change. She could certainly be forgiven, however, for glossing over some of the difficulties that most male-to-females suffer in adjusting to new lives as women who obviously used to be men.

In fact, those who do regret having surgery usually haven’t changed their mind about wanting to be female, but are disappointed with the results (picture Linda Tripp before she had work done) and with the way people now react to them, explains Dallas Denny, Georgia’s acknowledged expert on all things trannie.

Dallas, a retired psychotherapist, ex-man and the author of numerous scholarly articles, explains that early sex-reassignment clinics such as Johns Hopkins, were very selective of their patients, granting access to surgery only to men who would make convincing (read: attractive) women, like Christine Jorgenson.

When transsexualism was still considered a pathological malady, help was not available to just any Tom, Dick or hairy guy who walked through the door. Clinics wouldn’t take men who were too ugly, too old or too beefy. They required surgical candidates to divorce their wives in preparation of living as straight women, to change their names and to leave their careers to take jobs more befitting their new gender, such as secretarial work.

Really, the clinics reinforced sexual stereotypes, says Dallas, adding that once an early trannie had transitioned, she was encouraged to blend into the fabric of society and effectively disappear into what Dallas calls the closet at the end of the rainbow.

This brush-it-under-the-carpet approach was fine for the lucky post-op few, but it didn’t help those who’d been denied surgery or do much to educate the farm boy in Kansas or the Catholic schoolgirl in Boston who felt as if they must be the only people who had ever felt like this.

Small support groups have always existed in large urban areas, but it took the twin spurs of American social change—Phil Donahue and the Internet— to blow the lid of secrecy off the transgender community.

When Joan hit town in the early ’90s, the Atlanta Gender Explorations support group had just been launched by five men in various stages of transition. Since then, Atlanta’s annual five-day Southern Comfort conference has become the largest transsexual convention in the Southeast and AGE now boasts about 60 members, including 15 or so post-op vets, pre-op hopefuls and every variety in between.

There’s even a handful of that most exotic subspecies, the female-to-male. In keeping with the trannie rule of thumb of referring to someone as his/her target gender, we’ll use the masculine pronoun in describing Marik, who only recently started on testosterone. The hormone eventually will lower his voice, increase his muscle mass, cause him to sprout facial and body hair, and make him less inclined to ask for directions.

Marik is a former tomboy with painful memories of puberty: “I wasn’t allowed to cut my hair. It was down to my waist, but I always wore it up because I couldn’t stand to have it near me.”

A tad heavyset but filled with youthful energy and sporting a hip, androgynous shag, Marik possesses an infectious smile that would translate as cute in any gender.

Before the end of the year, he plans to have a hysterectomy, partly to hasten his transformation by halting the production of estrogen, and to have top surgery. Unlike a radical double mastectomy, which leaves grotesque scars, this specialized procedure will reduce the breasts and re-position the nipples to give the chest a flat, manly appearance. Together, the surgeries total around $7,000.

Marik has always liked boys, but identifies as queer. This, at first, seems a logical contradiction until he explains that he is a young, gay man trapped in the body of an 1 8-year-old girl, a concept that no doubt has already occurred to Aaron Spelling.

He anguished over gaining his parents’ support (score: 1 for 2), but that later may seem a piece of cake compared to finding success in the image-conscious world of the club circuit, which is why he is determined to find the money to pay for bottom surgery.

You have to be young and beautiful, he acknowledges, and I want to be ready to enjoy my 20s and party till I drop.

Which leaves him two choices, neither of which is ideal. One of the more notorious effects of testosterone on the female body is that it causes the clitoris to grow, sometimes more than an inch, and longer when aroused. An additional bit of surgery can lengthen it even more, to about the size of a finger. Marik concedes, however, that such an appendage is unlikely to attract very many takers on the other side of a glory hole, so he’s hoping he can raise the money for the deluxe model.

Phalloplasty was born on the battlefield early this century to patch up damage done by land mines and, in keeping with those utilitarian origins, the results are decidedly unpretty, especially when the recipient is starting from snatch.

It’s estimated that perhaps less than 5 percent of female-to-males bother to get phalloplasty (even the word has a nasty, almost-onomatopoetic ring to it). Paying more than $70,000 for an after-market package with no moving parts isn’t their idea of a bargain.

Again, those with weak stomachs will want to avert their eyes.

After sewing shut the vagina, the surgeon forms the faux penis from a chunk of skin, flesh and veins he carves from the patient’s forearm—call it robbing Paul to pay Peter. But, apart from giving the transman a reassuring bulge in his britches, the new member is a non-starter. It can only be put into action with the aid of the very unromantic, pre-Viagra penile pump and doesn’t provide its owner with much in the way of stimulation, unless your idea of ecstasy is having someone lick your wrist.

When I wear a short-sleeved shirt, I’ll just have to tell people I had a chainsaw accident, Marik says, shrugging. Nonetheless, he believes no self-respecting queen would be caught without his scepter, even if it doesn’t actually work.

Still, he’s confident that he’ll soon be flaming through Hotlanta. Asked who the young lady is who tags behind him, he says: Oh, that’s my friend. She’s a fag hag.

Marik’s transitional role model is Rayees, a bearded, 32-year-old transman so completely convincing that when he talks about attending an all-girls school in his native Pakistan, the conversation has the feel of a Candid Camera gag.

In fact, he explains, with perhaps a faint hint of pride: “I was always very masculine-looking and could pass as a young boy just by changing clothes. I knew in my heart I was anatomically wrong.”

At first glance, this situation would seem to be no small problem in a Muslim nation, especially when one’s father is a highly placed military officer, so he waited until arriving at grad school in the States before telling his family. Ironically, his concern was unfounded.

“In my country, daughters are considered a burden and a son is everything, Rayees explains. When I finally wrote my father, he called me immediately and said, ‘My son, why didn’t you tell me before?’ I just broke down and cried on the phone.”

Rayees had his surgery in Pakistan in 2000 (unlike his fellow transmen, he is offended when asked for details) and returned to the U.S. just in time to experience the downside of being a Muslim man in post-9-11 America.

“I feel like I’ve lost some of the female privilege I had because suddenly I’m viewed as a potential terrorist,” he says. “When I go to the airport now, I know I’ll be searched and harassed.”

Speaking of trannie horror stories involving the law, the saga of San Antonio’s Christie Lee Littleton stands as a Texas-sized raw deal. She had been a woman for 17 years and a happily married wife for seven when her husband became sick and died in 1996. Littleton’s subsequent medical malpractice suit was successfully challenged on the basis that, since she’d been born a man, her marriage must be considered same-sex and thus illegal under state law. Therefore, no widow’s right to sue.

The state Supreme Court refused to hear her appeal, effectively rejecting the idea that someone can change his/her gender, despite the fact that Littleton had a state-issued driver’s license, marriage certificate and a revised birth certificate that described her as a woman, and that she had been ordered to make support payments to her husband’s children during his illness. (It should come as no surprise that the Texas high court includes several George W. Bush appointees.)

If it were taken seriously as legal precedent, the decision could have far-reaching implications for genetic testing to establish gender status. (Imagine a horde of former East German athletes asking, I defected for this?)

Atlanta is among a dozen or so U.S. cities whose non-discrimination clauses extend to transgendered folk, and trannies have found greater acceptance through the political clout of the gay community, but more work is required to defeat decades of prejudice and misunderstanding.

In Georgia, as in most states, there are no laws on the books that define what it legally means to be male or female. Southern Comfort, a documentary film shot in Georgia about a tragic trannie love story, shows the last few months in the life of transman Robert Eads, who died of ovarian cancer after being refused treatment by several doctors in his hometown Toccoa. One of the doctors told Eads that seeing him in the waiting room might make the other patients uncomfortable. The movie has been shown on HBO and played theatrically in other large cities, but hasn’t come to Atlanta because some of the people appearing in the film are afraid their neighbors might discover their secret.

Jessica thankfully has no such tale of woe. Her main complaints now involve the basic inequities of belonging to what Simone de Beauvoir termed the second sex—i.e. women pay more for clothes, dry cleaning, health care, etc.

She also loses patience with her fellow Y-chromosome holders, such as when male colleagues question her software expertise. Then there’s the incident in which a grease monkey wanted to sell her a new car battery, even though she told him it was only low on water. Now look, little lady, batteries are complicated things … he began before she read him the riot act.

But other moments stick with her as well, such as the day her father first introduced her to a stranger as my daughter.

Her philosophy of life as a trannie boils down to this nugget: matter how bad things might get from now on, I won’t get upset because I know it’ll never be as bad as it used to be before surgery.