Prodigal Son (1994)

©1994, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Denny, Dallas. (1994, Spring). Prodigal son: A tale of noncommunication and rejection. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(7), pp. 23-26.

View Chrysalis Quarterly Pages (PDF)

Prodigal Son

A Tale of Noncommunication and Rejection

By Dallas Denny

My earliest and most vivid memory dates from the early 1950s. I was perhaps four years old. Certainly, it is a remarkable first memory, an exercise in prejudice with a lesson that an ordinary boy child would almost certainly have missed. But then, I wasn’t an ordinary boy child.

It was a hot summer day in Asheville, North Carolina, even inside the normally cool interior of the house. We needed provisions, but we had no car. My mother, not wanting to make the long walk to the market, allowed herself a luxury; she called to have the groceries delivered.

A half-hour later, a black gentleman of about sixty-five made his way up the outside wooden steps to the second-floor landing and knocked gently on the screen door of the kitchen. When my mother opened it, he handed her a sack of groceries. Perspiring profusely, he used his shirt sleeve to wipe the sweat away. I now realize he was Uncle Tomming when he said, “It sho’ is a hot day, Miz Denny.” My mother allowed that it was. He said, “Yep. Sho’ is a hot day. I hates to bother you, but could I trouble you for a cold glass of ice water?”

My mother smiled most pleasantly and fetched a red-handled ice pick and a red-and-yellow jelly glass from the cupboard. We didn’t have a refrigerator—one of my other early memories is of the iceman coming in with a block of ice dangling from a great set of tongs—so she opened the icebox and chipped off some slivers of ice and put them in the glass and filled it from the faucet at the sink and took it to him. The man, still standing on the landing, drank it, thanking her effusively. Mother smiled and asked him if he wanted more. He said that he didn’t, made his goodbyes, and trudged slowly down the stairs and across the dusty yard to the even more dusty road.

As soon as he was out of sight, my mother, with a look of distaste on her face, looked at the glass in her hand and then stepped onto the porch and threw it as hard as she could. The most vivid part of the memory is that glass, tumbling red-and-yellow, red-and-yellow through the air and rolling to a stop without breaking in the dust of the yard below.

I was dumbfounded, but I knew instinctively why my mother had thrown the glass. I had had no previous experience with prejudice, but her facial grimaces told the story; she somehow considered the man unclean or inferior. I knew it was because his skin color was not like ours. But it was patently clear he was in no way inferior; in fact, in their exchange, he had been operating from a position of moral superiority, being pleasant in the face of her obvious condescension. I knew that if I were to chance upon him in the street and tell them about the glass, he would smile sadly, unsurprised. I pictured him, coming back on another hot day with another sack of groceries, standing quietly, looking down in the dust at the glass. I felt his rage and shame, connecting with it in a way I couldn’t connect with my mother’s hypocrisy.

I didn’t say anything to my mother, for I knew that there was nothing she could possibly say to justify what she had done, and no way I could convince her that what she had done was wrong. I kept my mouth shut and my opinions to myself.

That was a pattern in my family—not dealing with issues. We would discuss our problems, but not in the depth and detail that situations demanded. We were just six people thrown together by happenstance, with little in common except shared genes. We were tolerant of one another, and even loved one another in the usual familial way, but our only bonds were those of family. Later, after my youngest sister was grown, she and my mother became close in the way that friends do, but with that exception, we acted out our roles mechanically and for the most part politely. It was our imitation of the Ward and June Cleaver/ Ozzie and Harriet 1950s nuclear family. It made for a comfortable and secure, if somewhat robotlike, life.

My mother and father took their duty as parents seriously. They worked hard. They kept me and my three siblings fed and warm and safe and tried to instill positive moral values in us, but on autopilot—like for instance by sending us to Sunday school but not bothering to go to church themselves. I received a good public education, and was given money to participate in band and other activities which imposed hardships on my parents, but they never complained. I didn’t realize until I was grown just how tight money had been when I was a child. The end-of-the-month suppers of fried bologna or hot dogs that I and my brother considered such a treat were actually a desperate attempt by my parents to make ends meet on limited funds. Yet despite the hard times, I wanted for nothing material. I was never hungry or unclothed or unhoused or unloved, and never went without medical attention. When I was eight, and hemorrhaging with German measles, my father swept me into his arms and ran with me through the French village of Beaugency to find a doctor. And every Christmas, under the tree there would be a profusion of wondrous toys my parents couldn’t really afford.

Unlike many transgendered persons, I was never abused, either psychologically or physically. When I was small, I would get switched or paddled, but never in anger, and never without deserving it. As I grew older, lectures replaced the hard-backed hairbrush and hickory switch. A lecture was worse than any spanking, as the lesson would be imprinted upon my soul rather than my buttocks.

But for all my parents’ efforts, they and I had no real communication. I grew up uncomfortable in their house, a mismatch to their 1950s sensibilities. My interests, musical tastes, political views, and aspirations were out of line with theirs. So was my intelligence. Everyone else was merely bright; I was brilliant. Much of what I said and did was incomprehensible to my family. I was smart enough to realize the importance of talking and acting like everyone else, but I was the bright one, and everyone knew it, even if I did frighten them a bit with my unorthodox political views. My intelligence did not translate into money or popularity or good grades at school; it just made of me a stranger. Perhaps that is why I was not the favorite son.

Every child thinks at some time that he or she is an orphan, and I was no exception. When I hit thirteen, I began wondering how my parents, both blue-eyed, had produced a hazel-eyed child. My siblings all had blue eyes, and I should have too, according to a book on genetics I found in the library. Blue eyes were controlled by a single recessive gene, it said. That meant two brown-eyed parents could have a blue-eyed child, but two blue-eyed parents could not have a brown-eyed child. It seemed my suspicions that I was “different” from the rest of the family had a genetic basis.

I don’t remember what triggered it—perhaps I mentioned my theory about the eye color—but one day my mother told me that although I was her biological child, I was not my father’s. She explained how she had come to conceive me, and how she had borne me at a time when the pregnancy of an unmarried woman was considered scandalous. She told me of her love for a married man, of the stress of her pregnancy, how she had fought to bear me and raise me—it was the first time I heard the word abortion—how she had married my father when I was about three years old, and how he had adopted me shortly thereafter.

It was something she had been holding in for a long, long time. I cried with my mother that day, sharing her pain and shame. And then it was over, and we never talked about it again, except for a brief mention now and again when we were alone together.

They Should’a Seen It Coming

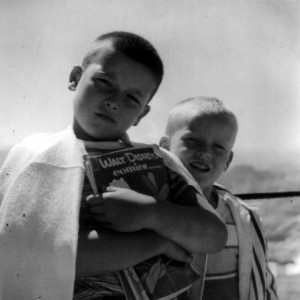

Although my crossdressing was “discovered” when I was about fourteen, early photos clearly show signs of my femininity. I was surprised to find these photos, for I had always thought that I had covered up very well.

We never talked much about my gender issue, either. It arose at about the same time. For a few months, I would guiltily put on my mother’s garments on the rare occasions when I was home alone, but I soon acquired my own rudimentary wardrobe. I would shave my legs and underarms, carefully rinsing the hairs down the drain. I would sit in the living room floor in panties, bra, and slip, applying my makeup with the aid of a hand mirror. The transformation never failed to astonish me. As a boy, I was ordinary-looking, but as a girl, I was just short of beautiful. Or so it seemed to me. I was aching for confirmation, but of course, there was none.

My first feedback came one day when my mother returned early and caught me, fully dressed, standing in front of the mirror in her bedroom. “You don’t look like a woman,” she hissed. “Take those clothes off this minute!”

Any confidence I might have had was immediately shattered. I took the clothes off and washed my face. That evening, my father threatened to make me walk the five miles to town, dressed, while he followed in the car. I suppose he thought I would look ridiculous, like a boy in drag. But that’s not what I looked like. With my delicate features and lack of facial hair, I looked like a fifteen-year-old girl. Or did I? My mother certainly didn’t think so. I wondered whether I was deluding myself. Later, when I began venturing out in public, I continued to wonder whether people were seeing me as an attractive young girl or a boy-in-a-dress.

Twenty-five years later, a piece of the puzzle suddenly clicked into place. I was talking to my therapist, telling her that all my adult life my mother had tried to convince me to cut my hair and wear a suit. “Dallas,” she would say (my name has always been Dallas). “You look so good in a suit. And men are wearing their hair shorter these days. You would be so handsome.” My therapist looked at me strangely, and said, “She told you that because she knew you weren’t really a man. She wanted you to do the things that would mean to her you were a man.”

Another piece of the puzzle fell into place about three years after that. I awoke one morning, about a year ago, with the sudden realization that my mother had said, “You don’t look like a woman.” She had not said girl—she had said woman. “You don’t look like a woman.” She had not seen a crossdressed boy, or even a girl. She had seen a woman, and not only a woman, but young and beautiful woman—younger and more attractive than she. Her own femininity had been threatened, and by her born-out-of-wedlock son, no less! No wonder she had trouble handling it!

We never discussed my gender issue—why I felt the need to dress in women’s clothes, how we were going to deal with this complication in our lives, whether I was going to do it again. Obviously, my parent were communicating with each other, for they took me to a psychologist to talk about my crossdressing issue, and to Walter Reed Hospital to have my genitals examined. My private parts, although on the small side, were normal—no doubt to the relief of my parents—and the psychologist reported that my crossdressing was just something I was going through as part of adolescence. I had managed to convince him of that by lying desperately. I wanted to tell him, to scream out the truth, but I sensed that telling him the truth, or letting him guess the truth—which was that I wanted to be a girl more than anything in the world—would have been very dangerous to me.

One morning my mother asked me, point-blank (with no warm-up), if I was planning to have a sex change. I that such things were possible, but I had heard on the radio that there was only one treatment center, at Johns Hopkins, which took only two cases a month. Surely, those accepted would have ambiguous genitalia, be living as a member of the other sex already, or have wealthy parents. What chance did I have of getting treatment? “No,” I told her. “I don’t want to change my sex.” And that was the end of that conversation. And yet that night, I prayed on the first star I saw that I might become a girl.

In these days in which nearly every family is termed dysfunctional, I won’t say my family was. But we weren’t the perfect family, either. We were a self-sufficient little unit with limited coping skills and limited communication, a family that never went to the mat with its issues. We discussed them to a point, and no further. After that they were just swept under a rug in the hopes they would go away.

My gender issue didn’t go away, of course, although I pretended along with the rest of the family that it had. Eventually, I was unwilling to pretend any longer. One evening in 1989, while I was talking on the phone long-distance to my mother, she once again asked if I planned to have sex reassignment (I had provided her with cues enough for her to guess it). I told her I did.

She said, in a sorrowful voice, “Dallas. I didn’t have a little girl. I had a little boy.”

I’ve wished many times since then that I had been quicker on my feet. I should have said, “Mother, you had me.” But I didn’t. I said nothing, and that was the last time I heard my mother’s voice. That was nearly five years ago.

Throughout those years, I’ve written regularly, even though I received a request from my mother via my sister asking me to have no contact. I’ve honored my parents’ request not to call or visit. I’ve seen my sister Donna once, for perhaps fifteen minutes (that was in 1991), and I’ve spoken on the phone with my brother and his wife several times, and my other sister, Tanya, twice—both times when she was in crisis. That’s it for the bosom of my family.

My mother has written twice, once to say that I would never be a woman and that any doctor who would take a knife to me should be killed, and once, several years after that, to say it would be OK to write, so long as I did not send pictures or discuss my transsexualism. Gee, thanks, Mom.

I’m in my mid-forties, and my parents are in their seventies. I live with the certain knowledge that I will one day get a telephone call or a letter from my brother or one of my sisters, or perhaps a cousin or aunt, saying one or both of my parents are dead. What hurts is I know that by the time I get the news, whoever has died will be safely interred; the delay will be purposeful, to ensure I won’t embarrass anybody by showing up at the funeral. I don’t assume they’ll do it; I know they’ll do it. I already hate them for it.

I was far from a perfect child. I was wilful and at times cruel, petty, and inconsiderate. I was rebellious during my teen years. But I had my good points, as well. I was just a human being growing up, trying to mess with the rigidly defined lifestyle of my parents, with its taboos on dress and behavior, trying to understand who I was while living day to day with those strangers who had been assigned to me, my family, and trying to put on an act that would convince me as well as those I loved that I was male. When I made a mistake, when I did something wrong, when I was difficult to understand and deal with, I was still part of the family. But the moment I showed my true face, the person I really was, I was excluded, expelled from the family.

If I had murdered someone, I would have been disgraced, but still part of the family. But for being true to myself, for finally daring to live my own life—I believe they call it growing up—I was excised, like a cyst.

What hurts about the rejection is that it came without discussion. Certainly, I had figured out what I wanted to do with my body and with my life, and would probably have gone forward with my plan for sex reassignment despite anything that might have been said, but I would have liked at least a hearing, a chance, after all those years of silence, to explain what I felt and why I was making the decisions I was making. But I wasn’t allowed contact, even though I was still in the male role. I never got a chance to break the silence.

Rejection after discussion would have been understandable, even if unacceptable; rejection without discussion is unthinkable. Even after five years, I still have trouble believing I have been so heartlessly and thoroughly cut out of my family.

My mother has always been the dominant force in the family. When she wanted a new car, we got one. My father would grow depressed and angry at the thought of working to pay notes on a car he hadn’t wanted, but he would accede to her demands. When he wanted to take a job in a national park in Wyoming and everyone but Mother wanted to go, we stayed in Tennessee.

My mother is still the boss. When, if ever, she is ready to accept me, warts and all, the rest of my family will begin to come around. But until then, I have no family. There are just some people I never really knew who sometimes send me birthday and Christmas presents.

I’ve no doubt the family cares for me in its own fashion, but it isn’t a warts-and-all kind of love. It’s a conditional love—and aren’t families supposed to love unconditionally? It’s as if my family’s need for me to be what they wanted me to be was more important to them than who I really was. In fact, I think that’s the crux of the matter: their love is selfish, something which suits their purpose and has little to do with genuine affection. That, I now realize with sadness, was what my family was, and remains: a group of people who cared for and adhered to each other because they thought they were supposed to. So long as no one rocked the boat, the family could cling to its mutual illusions. But once I stepped outside the norm, once I stopped pretending to be one of the Dennys and dared to be myself, that was it. It was easier to remove me completely from the family than to give up their illusions.

My feelings about the rejection have ranged from bewilderment to sorrow to anger, but the overriding emotion, the one which came first and which has lasted longest, is disappointment. It reinforces my belief that my family was just an assortment of people I drew by chance, like one draws a roommate in a college dorm. My family is made up of imperfect human beings, unable to love unconditionally, unable to rise to a challenge, unable to communicate. I’m sad for them, for I gave them a wonderful challenge, and they have failed to rise to it.

My mother, I’m afraid, will always be the sort of person who will smilingly give someone a drink of water and then throw away the glass. She has cast me away like a red-and-yellow jelly glass because the script of my life surpasses her understanding and her ability to love.

It makes me sad that my family, that group of people who never communicated, do not know me any longer. Dammit, I think I’m a pretty wonderful person. I’m worth knowing, and I’m deserving of love.

Perhaps one day my family will, like me, grow up—or at least start communicating.

I hope so.