First Contact: Transgender Community Educational Efforts in the Late Twentieth Century (Keynote, 2009)

Why is trans education important? Well, ask yourself if there was ever a time in your life when you badly needed information about who you were, what you could do about it, who you could be, and how you could plan your life. If you’re like me, you were at one time or another, and maybe even for half your life, desperate for such information.

It’s difficult to make smart decisions when you’re flying by the seat of your pants. And it’s difficult to make good decisions when you have only one, or perhaps two, sources of data.

Despite all the educational efforts from the 1950s on, it was horribly difficult for even an intelligent, well-educated person to find someone to talk to about transsexualism or crossdressing. In fact, you had to be pretty lucky.

I know I had a horrible time myself. Did anyone else in this room have a hard time finding information or help?

In the last five or ten years, we’ve been deluged with information. We have so much we have a hard time sifting through it all.

But it wasn’t always like that. Consider the 1950s.

It was a decade of fear.

I can’t help myself. Four years after my presentation, Jan Brown and I viewed an installation of Arthur Fellig’s photography at Manhattan’s International Center of Photography. Felig, known as Weegee, was a crime reporter for many years. Titled Murder is My Business, the exhibit consisted of black-and-white photos; several were of crossdressers in paddy wagons. I’m reproducing two of them here. The first, taken in 1939, shows two people looking obviously unhappy about what is happening.

The second shows a young man acting startingly campy. Good on him!

Those were not good years for us.

End of digression.

Men and women around the country go in the dark of night to buy black market pornography not for its images, but in the forlorn hope it might contain a tidbit or two of useful information.

For the few who had found community, there were still risks.

In Los Angeles, heterosexual crossdressers sit on chairs in a circle in Virginia Prince’s living room. A paper bag at their feet contains stockings and high heels. They look uncomfortably at one another, convinced everyone else in the room is a spy from the FBI. At a signal from Virginia, they open their bags and put on their hose and heels.

The risk was not imaginary. A few years later, Virginia would find herself under threat of prison for publishing her crossdressing-themed magazine Transvestia.

In New York, small groups of crossdressers are having weekend retreats in the Catskills. To one meeting, they dare to invite psychiatrist Hugo Beigel (they thought he was a friend), who writes a condescending article about the experience and publishes it in The Journal of Sex Research.

Beigel, H.G. (1969). A weekend in Alice’s Wonderland. Journal of Sex Research, 5(2), 108-122.

There was no rebutting Beigel, for, with the exception of Virginia Prince, anyone who was publicly transgendered couldn’t get published in the professional literature.

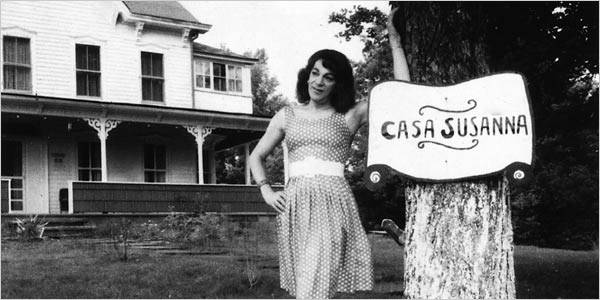

Okay, another after-the-fact digression. Photos from those weekend retreats surfaced a few years ago in Manhattan when collectors Michael Hurst and Robert Swope discovered hundreds of them in a bin at the store of a Manhattan antique dealer. When they looked closely, they could see the women in the photo had male bodies. They wasn’t sure what was going on, but the images spoke to them and they purchased them all. Photos from the acquisition were published in 2005 by powerHouse Books with a title that uses the actual location of the retreats: Casa Suzanna. Hehe, I just now ordered a copy from Advanced Book Exchange. Six bucks with shipping. Ka-CHING!

Now Harvey Fierstein has written a play based on the book. Called Casa Valentina, it opens on Broadway on 23 April, 2014. I just purchased a ticket for the Wednesday matinee on the 30th.

End of digression. I promise it won’t happen again.

Gender Education in the Wake of McCarthyism

Let’s stop here to think about those McCarthyist times. The first season of the popular AMC television show Mad Men does a pretty good job of capturing the paranoia and pressure to conform of those times. The veterans were home after saving the world in WWII, and things were going to be good. But under every rock there was a Red, or, worse, a homosexual. Both men and women took extreme pains not to appear “different.” Businessmen commuting to and from New York City were careful even about the books and newspapers they were seen reading. So can you imagine going at night to a stranger’s house carrying hose and heels in a brown paper bag?

Gender education in this decade of fear was done one on one— expectant men being interviewed in diners in hopes of being allowed admission into a secretive group of crossdressers, drag queens taking baby drag queens under their tutelage, Christine Jorgensen replying to hundreds of letters from men and women desperate for sex change surgery, referring them to Dr. Harry Benjamin and the few other physicians who would see them.

1960s

TOP DOWN, AUTHORITARIAN LEADERSHIP

Leaders in the fledgling transgender community were quick to realize they had to find ways of reaching larger numbers of people. Magazines like Virginia Prince’s Transvestia, Lee Brewster’s Drag, and Selbee Magazine’s Female Mimics could be found here and there. They were difficult to locate, but once you found them you would be able to correspond and go to meetings and events (they might be halfway across the country, but there were places you could go).

Things were starting to look up.

By the 1960s, nonprofit organizations were being set up to disseminate information about crossdressing and transsexualism. These were what I call top-down organizations. Information (and imperatives, in the case of Virginia Prince) flowed downward, to the bodies of transsexuals and crossdressers.

Virginia Prince was doing presentations at colleges, civic organizations, and churches and starting organizations for heterosexual crossdressers. And Louisiana, of all places, saw the formation of perhaps the first organization set up specifically for gender education. With the financial backing of Reed Erickson, the Erickson Educational Foundation was formed to distribute information on transsexualism to physicians, the media, and transsexuals themselves. Under the direction of Zelda Supplee, The Erickson Foundation published and distributed brochures, booklets, newsletters, and magazine articles, and they got the word out by advertising in the few places that would accept their ads.

The Erickson Foundation was an important step forward in gender education, for it took advantage of media to reach as many people as possible. Distributing information was as easy as reading a letter, stuffing an envelope with as much information as you could for one-ounce-over postage, and dropping it in the mail. The envelopes largely replaced the one-on-one interviews and the drag moms, but at a price—when you’re stuffing envelopes all day, you have little time to meet someone for a screening interview or be someone’s drag mom. Personal contact was by necessity limited.

I have a couple of stories to tell here about how this model of gender education came about.

On the crossdressing end, Virginia Prince found herself in deep trouble with the Federal authorities for mailing homosexually-oriented materials (can you imagine? We’re talking about Transvestia, that bastion of heterosexual thought here!) through the mail. To her credit, Virginia refused to stop publishing or turn over her list of subscribers to the feds. Because of this, she was found guilty of a felony and put on probation. She was deathly afraid of dressing in public because she figured (correctly, I think ) that she might be sent directly to prison if she were to encouter the police—and so she came up with the idea of doing presentations on crossdressing to civic, educational, and religious groups. It provided the perfect cover and set up a dynamic that would keep her busy for the rest of her life.

In the 1960s the prestigious Johns Hopkins University opened a sex reassignment clinic. As a result of this, similar clinics sprouted like mushrooms all around the country. An important book, Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment, edited by Richard Green and John Money, presented an interdisciplinary treatment model for the treatment of transsexuals. And for the first time, psychologists and physicians working with transsexuals held an international symposium.

This work with transsexuals did not come about by chance. Aaron Devor has documented the importance of FTM Reed Erickson in all this. With inherited money he funded Money’s research, the Hopkins gender clinic, the publication of Green and Money’s book, the first international symposium on gender identity, and the Erickson Educational Foundation—all this and flying saucers, too. And oh, yes, he funded the first translation of a book on acupuncture into English.

1970s and 1980s

- The 1970s and 1980s saw slow growth in the transgender community. Of special note were:

- The riots at the Stonewall Inn in 1969

- The formation of Tri-Ess in 1976

- The publication in 1979 of a hate-filled book on transsexualism by Janice Raymond, The Transsexual Empire.

- The publication in 1979 of an article by Jon Meyer and Donna Reter in Archives of General Psychiatry which purported to show “no objective advantage” to sex reassignment surgery in male-to-female transsexuals. This study was immediately contested and in fact seems to have been fraudulent. Certainly it stands in contrast to every other outcome study of transsexualism published—ever.

- National tours and concerted media efforts by both Meyer and Raymond to publicize their inaccurate works.

- Lobbying of medical associations by Meyer and insurance companies by Raymond in which they called for an end to sex reassignment nonreimbursement by insurance companies for transsexual-related expenses.

- The formation in 1987 of the International Foundation for Gender Education, which provided on a national level intellectual and physical space for transsexuals and crossdressers to meet and interact. Wisely, IFGE refused to be the authoritative source of all information. As an example, when asked by Sabrina Marcus to start a trans* conference in the Southeastern United States, Executive Director Merissa Sherilll Lynn said, “No, we won’t, but we will come to the South and show local groups how to start one themselves.” IFGE did just that. The result was the Southern Comfort Conference.

- The formation of the first computer bulletin boards in the mid-1980s; these allowed anyone with a computer and a telephone to get information and talk with like-minded others.

- The advent of electronic self-publishing. Computers and dot matrix printers beat mimeographs and photocopying all to hell when it came to putting out a low circulation monthly newsletter. And the introduction of the Macintosh and later the replacement of DOS with Windows with WYSIWYG allowed production of high-quality printed materials on a budget. Goodbye, hot lead type!

The 1990s

TOP-DOWN ORGANIZATIONS DISAPPEAR

The 1990s saw rapid growth of the transgender community and bridges built between the gay and lesbian, academic, and medical communities, even as the national nonprofits silently failed for lack of funds. Support groups flourished. The transgender political movement was born. And of course, there was the Internet, with e-mail and the world wide web.

At first, of course, few people had e-mail—but more transgendered people than not are geeks and take naturally to computers. Case in point—me! I bought a Commodore VIC-20 computer in 1981 and got online for the first time in 1983. By 1992 I had e-mail and by 1993 I was sending out bi-weekly compilations of transgender-related news stories and magazine articles—the first such effort, I believe. I remember there being 6 to 10 articles per week. Anyone who subscribes to the Yahoo group Transgendernews today knows there are 40 to 50 stories every day!

The Web One, as it has been called, provided yet another way to reach large numbers of people, and at a substantial savings over stamps and envelopes. There were no printing bills, no envelopes to purchase, no stamps to buy and lick. And the web! It was useful on all sorts of levels.

Meanwhile, the organizations—all this time AEGIS, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit I founded in 1990, Tri-Ess, and IFGE had been paying a lot of printing bills and licking a lot of stamps.

By the late 1990s most people had e-mail and web access and it was growing increasingly clear the Internet was changing everything. New and largely web-based organizations were forming, and anyone with even a rudimentary knowledge of HTML could throw up a website. This paradoxically allowed an individual with no budget to reach virtually unlimited numbers of people—often with biased and inaccurate information. The Erickson model was starting to look inefficient. The top-down model of information dispersal was on its way out.

Let me just say a word about the infrastructure necessary to provide information under this—let me call it Erickson Educational Foundation—model. Space was required—if you were lucky, you had an office suite; if you weren’t, you ran your organization out of your living room. If you were lucky, you were able to pay at least one staff member. If you weren’t, you and hopefully some of your friends and volunteers worked long hours with no compensation. If you were lucky, you got enough contributions to pay for stamps and printing; if you didn’t, you paid a good portion of expenses out of your own pocket. Few organizations were so lucky as to meet their expenses.

Moreover, money, always scarce in such a tiny community, was growing more scarce, for more and more donations were being funneled not for educational work, but toward political change through new groups like GenderPac.

Note, however, that the flow of information was still mostly downhill. There were certainly forums that allowed people to chat, but almost everything, from e-mail, to pleas for money, to gender education materials, flowed downhill, from the organization (or, increasingly, the individual who constituted the entire organization) to the end user.

Now, in 2009, we’re seeing the winding down of the first decade of the twenty-first century. And what are we seeing? The flourishing of Web 2 and the winding up of Web 3.

Web 2 is characterized by social interaction sites. I’m talking about MySpace,and Facebook, and, lately, Twitter, and several hundred similar sites. And there are blogs.

What makes Web2 different from Web1 is interactivity. Now you can both follow people and have followers. You can share your interests and personal history with others and learn the interests and histories of others. The flow of information once again goes both ways, just as it did in the 1950s. It’s a departure from the top-down model of the past.

And the future? Consider Web3. What’s Web3? Well, mostly we don’t know yet, but we already have virtual worlds like Second Life and There in which you can walk around. You can look at any objects from any point in space. You can see behind an object, its top, its bottom, all the while you are speaking in voice or typing to a friend who may physically be in China or Alberta. There are applications for the Macintosh and Windows 7 that turn the two-dimensional WYSIWYG desktop into three-dimensional space. We’ll talk more about Web3 and other new developments in the follow-up session after the break.

In the time left I’d like to hear from all of you about your personal experiences in both gaining information and passing knowledge on to others.