Not Screwed Up Enough (2013)

©2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Denny, Dallas. (2013, 13 November). Not screwed up enough: Managing trans identity then and now. Keynote at Trans Awareness Week, University of Missouri at Columbia.

I was honored to be asked by The Triangle Coalition to present this keynote. I was treated like royalty while in Columbia.

Not Screwed Up Enough

Managing Trans Identity Then and Now

By Dallas Denny

Hi. I’m going to talk today about identity: yours, and mine, and how dramatically and wonderfully things have changed since I was young. I’ll start with a description of the treatment system which arose in the 1960s—a medical model which viewed us only as patients—and I’ll describe how that evolved into the varied and diverse community of today. Then I’ll talk about the present and why it’s important to preserve our history for those who will follow.

Today, as I have visited your campus, I have seen every sort of gendered presentation. We live in an age in which we can construct our gender in any way we want, as if from a menu, as if we’re picking fruit from a tree. I’ll have one of these and one of those, and pass on THAT. We can even construct our own pronouns—he, she, ze, sie, s/he, or no pronouns at all, please. It’s wonderful. And to make things even better, we can change our gender identity and presentation any time we want. As often as we want. As outrageously as we want.

Trans Identities Then

The people in this room, and others like us, have created this splendor of gender—but things weren’t always like this. American society was once rigidly divided along gender lines—and not all that long ago. Dress, hairstyle, education, employment, behavior were all tightly controlled. Those who strayed in even the smallest ways faced rejection and ridicule. Here are two examples.

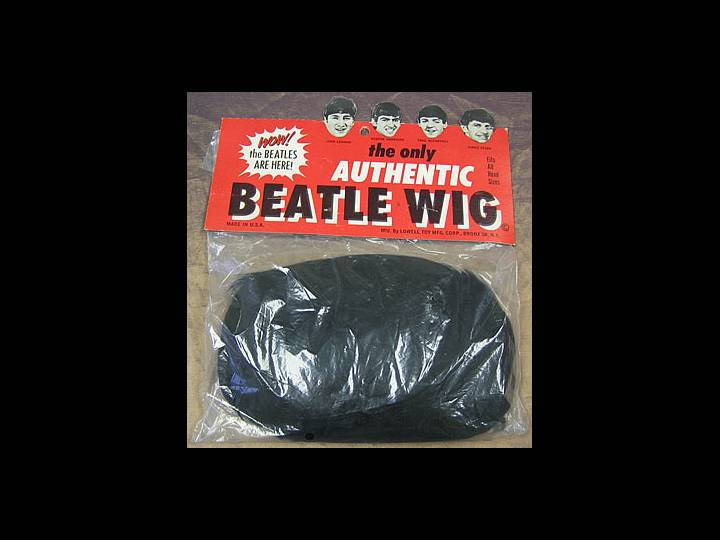

This is the cover of the first LP by the pop band The Beatles. They were immediately and widely attacked for their hair, which as you can see, wasn’t even that long.

They were called “Mop Tops” and Beatles wigs were sold as novelties.

In the 1970s needlepoint and macramé weren’t hobbies ordinarily associated with professional football players. Sports fans didn’t know what to think when NFL defensive lineman Rosey Grier published a book about needlepoint for men. Considering his size and reputation for fierceness, I think people were a bit afraid to confront him—but the fact that Grier was in the news for years because of his book says a lot about American culture of the time.

But it wasn’t a joke for transpeople. We were tightly confined into roles and presentations we hated and couldn’t escape.

There was a monkey wrench in all this, however—transsexuals.

By transsexuals, I mean people who, in the parlance of the day, changed their sex.

In 1953, Christine Jorgensen rocked the world of binary gender when she returned from Denmark as a woman. She had left the U.S. two years earlier, as a man named George. For the first time the world, including its scientists and physicians, were faced with the possibility that sex wasn’t immutable, that sex could be changed. Heresy!

The slide shows only a small percentage of the reporters and photographers who mobbed her on her return to the U.S. Much of their coverage made fun of her, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. Journalists tracked her for the rest of her life.

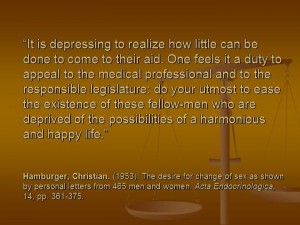

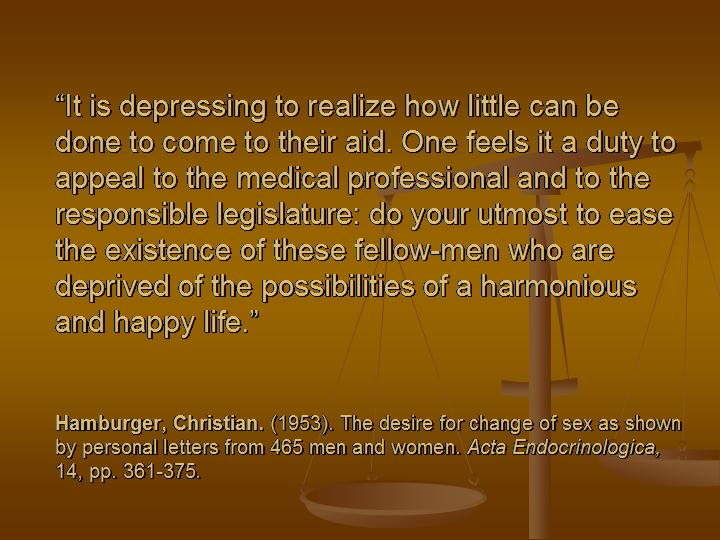

When the transsexuals of the world learned about Jorgensen’s sex reassignment, they responded with requests for the same hormonal and surgical treatment she had obtained in Scandinavia. Hundreds wrote to her and Christian Hamburger, her doctor. There was a problem, however. Hamburger hadn’t considered doing even a second sex reassignment.

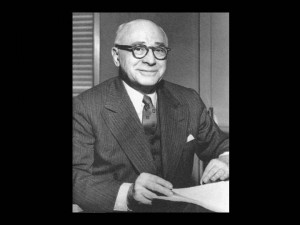

And so, transsexuals turned to sympathetic physicians like this man. His name was Harry Benjamin, and he lived to be one hundred and one years old. He maintained practices in New York and San Francisco and prescribed hormones for hundreds of transsexual patients. Alas. Thousands more, including myself, didn’t know about Benjamin or others like him, and went without treatment.

Here, Christian Hamburger argues for the necessity of treating transsexuals. However, transsexualism was met with stiff resistance from the medical community. Psychiatrists called sex reassignment “collusion with delusion” and “collaboration with psychosis.” Transsexuals were presumed to have a mental illness that made them want to change their sex and every attempt was made to “cure” them—forced hospitalization, electroconvulsive therapy, psychoanalysis, even lobotomies. Nothing worked. There were no cures.

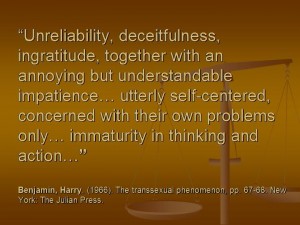

In 1966 Harry Benjamin described the “syndrome” of transsexualism in his book The Transsexual Phenomenon. Transsexualism was a mental illness, and since no treatment known to medical science could “cure” transsexuals of their wish to change sex, it made sense to relieve their pain (in extreme and select cases) by providing hormones and surgery. In other words, transsexuals deserved the same sort of palliative pain-relieving care as terminal cancer patients, and for the same reason. This was the birth of the medical model. We were patients, and nothing more.

It was, I believe, the only way Benjamin could have possibly sold sex reassignment to a hostile medical community. I’m convinced he meant well. There’s every evidence Benjamin empathized with his patients. He was, I believe, an extraordinarily good and kind man.

Nevertheless, the medical model Benjamin created, while providing an ethical basis for sex reassignment, caused immense misery for transsexuals. The gender clinics which arose—there were once more than forty in North America—turned away far more applicants than they accepted, and treated those accepted for treatment in horrible ways.

Horrible how? The clinics used the promise of hormones and surgery like a carrot on a stick. Some clinics required their married patients to divorce, some required their patients to leave their high-paying jobs to take jobs associated with their target gender, and they all pressured them to dress and behave as sexual stereotypes—lots of makeup and dresses for male-to-females, beards and suits and ties for females-to-males. No compliance, no hormones. No compliance, no surgery.

Sidebar

Please keep this in mind for a minute: the clinics required transsexuals to be sexual stereotypes.

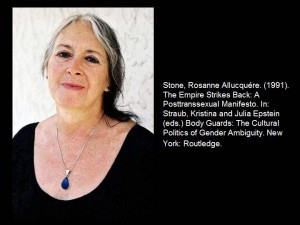

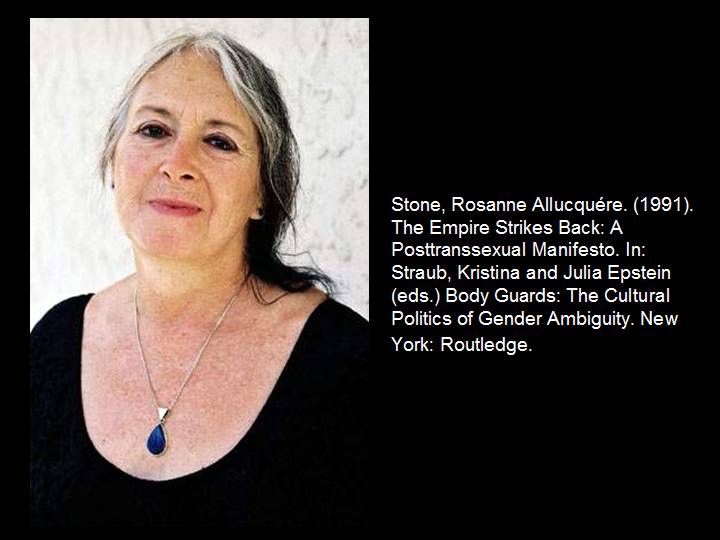

In the late 1980s Rosanna Allucuére (“Sandy”) Stone wrote a groundbreaking essay called “The Empire Strikes Back.” The empire to which she was referring was The Transsexual Empire, the title of Janice Raymond’s epic rant against transsexualism and transsexuals. Raymond wanted to “morally mandate sex reassignment out of existence” and came close to succeeding.

Stone, whose essay is sometimes pointed to as the opening salvo of the new field of transgender theory, pointed out that transsexuals quickly learned to show up at the clinics dressed as the very sexual stereotypes the doctors were expecting. It was necessary in order to get treatment. I didn’t know that, as you’ll soon discover.

Interestingly, this has been the basis for attacks by feminists and others upon transsexualism and transsexuals. The attackers claim transsexuals have naïve and stereotyped notions of femininity and masculinity. That’s absolutely not true. It was forced on us by the gender clinics. Most transsexuals are in fact not sexual stereotypes, and few of us are naïve about gender, for it has been an issue for our entire lives.

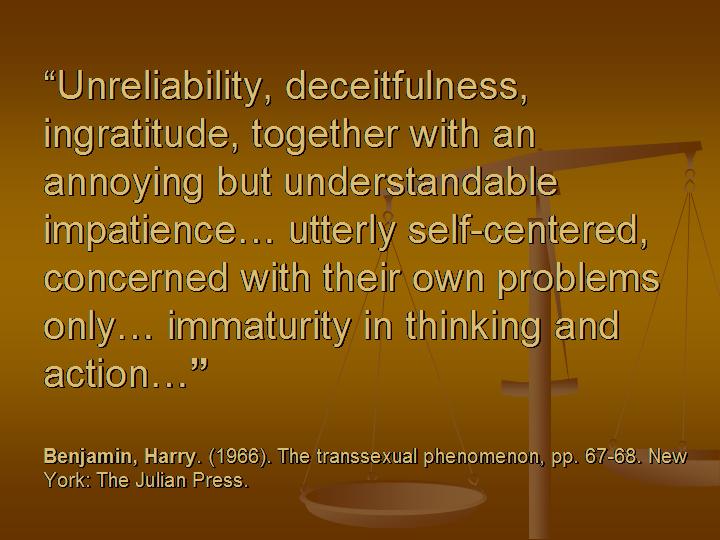

The psychological and medical literature which resulted described transsexuals as some of the most psychologically messed-up people on the face of the earth, individuals debilitated by their desperate desire to change sex.

… and this from the physician most sympathetic to us!

End Sidebar

Now let me make all this personal. Let me show you just how crazy this was. Consider: if I’d gone to a doctor for any other life-altering treatment, being a stable person would have been desirable. But for sex reassignment? No, no, no.

I’m going to tell you something known until now only to me and Dr. Embree McKee of the gender identity clinic at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. I’m not a transsexual.

At least that’s what Dr. McKee told me in 1978.

I had just given the clinic $500 for the privilege of taking a battery of psychological tests I had been trained to administer and could have given to myself for free— and THAT’S what the Rorschach told them?

I had asked the doctors at the clinic for help in living as a woman. They told me that wasn’t going to happen because—wait for it—

I wasn’t screwed up enough to be a transsexual. No, no, no, I’m serious. I wasn’t screwed up enough.

Here’s what Dr. McKee told me:

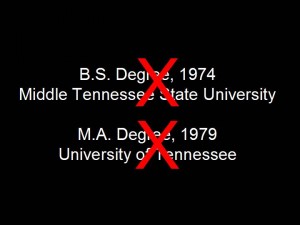

I had two college degrees. If I were transsexual, how was I able to hold myself together long enough to earn them?

Diagnosis: Not screwed up enough.

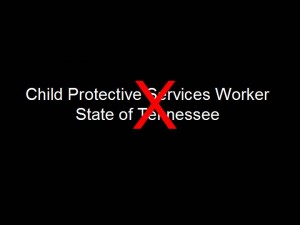

I had a position as a child protective services worker for the state of Tenneessee. If I were transsexual, how was I able to keep it?

Diagnosis: Not screwed up enough.

ad been married—in my original gender assignment—for six years. How could a transsexual possibly do THAT?

ad been married—in my original gender assignment—for six years. How could a transsexual possibly do THAT?

Diagnosis: Not screwed up enough.

I couldn’t have a college degree and be transsexual. I couldn’t have a job and be transsexual. I couldn’t be married and be transsexual. But I COULD be screwed up and be transsexual. My problem—I wasn’t screwed up enough!

And so the doctors told me there be would be no hormones or surgery for me. Not from Vandy, and not from anyone else.

I took myself to Vanderbilt’s medical library and consulted the literature of transsexualism, which confirmed what I had been told by Dr. McKee. Transsexuals were shallow people with character and personality disorders and criminal records. Dr. McKee had been right. I wasn’t messed up enough to be a transsexual.

But—but—but if I wasn’t transsexual, then why did I have such a desire to live as a woman?

It wasn’t easy to fly in the face of medical science, but I somehow managed. I didn’t have a support group. I didn’t have anything sensible to read. There was no internet, no Facebook. I didn’t even know anyone who was transsexual. I had to do it on my own. Let me tell you—it wasn’t easy.

Against all odds, I found hormones. I transitioned gender roles. I had surgery. Medical science, for all its tradition of rationality and progressiveness, was wrong. I, and not doctors, am the ultimate authority on who I am. And you—every single one of you—is the authority on who you are.

I often think of the thousands of others who became grist for the mill of the gender clinics and never realized that.

So—how did we get from the restrictive medical model to this splendor of gender I see today? I’ll illustrate.

In the mid-1980s anthropologist Anne Bolin studied a large trans support and social group in Colorado. She found members were expected to choose from just three identities—drag queen, crossdresser, and transsexual. Once they chose there were clear expectations about what they were and weren’t to do. Those identifying as transsexual were expected to transition and sometimes pressured by their peers to hurry along with things. If someone identifying as a crossdresser or a drag queen was even thinking about trying hormones, the reaction would be one of horror. Everyone was expected to stay inside their box.

That was the way things were when I made my transition in 1989. I’d been looking unsuccessfully for community all my life, and when I finally found it, I wound up in an old-school transsexual support group. “Our girls come to us with a birth defect. When they leave here they’re cured and have a wonderful life and no one knows about their past.” I wound up leading that group, and pretty soon my views were differing from those of the founders. There was tension, and I left and started the nonprofit American Educational Gender Information Service. For eight years AEGIS maintained a telephone hotline, published a magazine and several newsletters, distributed tens of thousands of flyers, and did direct intervention to prevent discrimination and stand up for the jobs of transsexual and transgendered people.

In the early 1990s I and dozens of other activists were rebelling against the medical definition of transsexualism and the treatment system that arose around it—and, although we didn’t realize it at first, against the binary gender system. We were talking about terminology and identity in the pages of newsletters and magazines and at conferences and face-to-face and over the telephone. Dozens, and even hundreds of us.

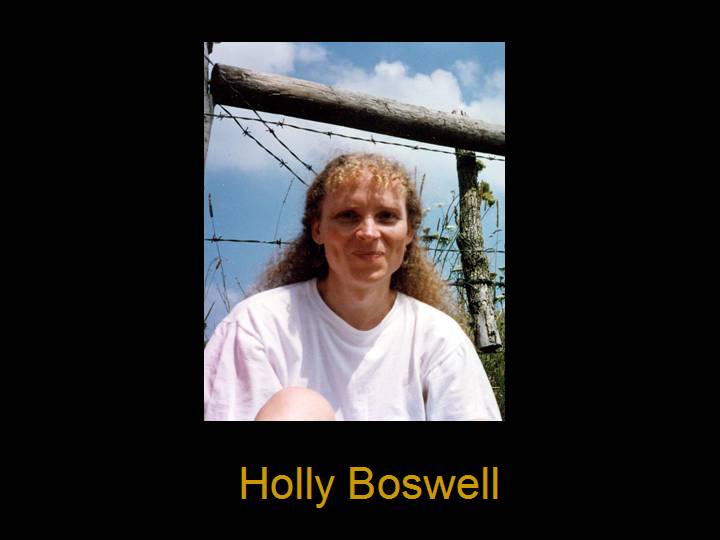

One of the terms we were batting around was transgender. Cristan Williams has shown through her research it was used by a number of people over the decades, including Virginia Prince and Christine Jorgensen—but it was reintroduced in 1991 by Holly Boswell in an article called The Transgender Alternative.

[Boswell, Holly. (1991-1992, Winter). The transgender alternative. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(2), pp. 29-31.]

Holly’s essay was published simultaneously in AEGIS’s journal Chrysalis Quarterly and a magazine called Transgender Tapestry (which I would one day edit). In it s/he argued for free expression of gender not limited by existing roles like transsexual and crossdresser. In other words, an anything goes transgender identity, a new option.

Holly’s essay was the seed for what I call the healthy transgender model—a new way of viewing us that is not based on pathology, but upon us as whole and sane people. There’s lots of interesting things I could say about this model, but for now I’ll just say it’s now the reigning model; only a few diehards cling to the medical model.

By 1993 the term transgender was being used widely by the press and within our community. When Anne Bolin—remember her? The anthropologist? When she attended Atlanta’s Southern Comfort Conference in 1993 she found attendees defining themselves and their gender identities not in the three ways she had written about less than a decade before, but in every imaginable way, varied and idiosyncratic. She described it as a splendor of gender. I love the term and use it as often as I can.

[Bolin, Anne E. (1994). Transcending and transgendering: Male-to-female transsexuals, dichotomy, and diversity. In G. Herdt (Ed.), Third sex, third gender: Essays from anthropology and social history, pp. 447-485. New York: Zone Publishing.]

Since 1993 the term transgender has flourished. Certainly not everyone likes it, but it’s now used as an umbrella term to describe people who vary from prescribed gender roles—and it’s now an identity term, used by individuals to define and describe themselves. “I’m transgendered.” I’m a transgendered woman.” I’m a transman.” “I’m trans.”

And so, that’s how we got to where we are today. With the floodgates opened, we spilled through and continue to spill through in a colorful rainbow.

Identity Today

In this new age of freedom of gender identity and expression, how can we choose from the many identities and paths that are open to us? Need we even choose? Are there cautions?

Of course there are cautions. There are always cautions.

First, some among us have a deep and abiding desire to change our sex—to alter our bodies and manage our identities in a way that allows us to live as a member of the sex to which we were not born. Many who would once have described themselves as transsexual now use other terms, but whatever we call ourselves, permanently changing gender is a difficult path to walk and we behoove ourselves to walk it carefully. If we take hormones, we require medical monitoring for the sake of our health. If we transition, and often even if we come out, our relationships are stressed and often broken. We may find ourselves rejected, unemployed, and facing harassment and danger on the streets. Support groups, therapists, health clinics, our doctors— we need all the help we can get. Few make it through unscathed.

All of us—not only those who change their public gender—need that support. We all face haters. We all face rejection by our families and discrimination. We all face stress. And however we identify and for whatever purpose we take them, if we take hormones we need to have our blood chemistry monitored.

What we are doing—all of us—is managing our identities. Once that meant negotiating our way from male to female or from female to male without self-destructing— I wrote a book about just that, in fact—but today things are more complicated. Today we might not be going from one gender to another. Today we might not permanently inhabit any particular gender. We might make up one of our own. Today we aren’t necessarily trying to pass. And today we’re no longer ashamed. We’re proud, and we proclaim it loudly—with our bodies, which we modify not only with hormones and surgery, but with piercings and tattoos; with our clothing, which may be a blend of items worn by men and women; and on the internet, through social media and websites and discussion boards and video sites like YouTube.

When you change your gender it generally sticks. Few people—and almost no one who has followed the WPATH Standards of Care—have a second sex reassignment. But when you’re gender-fluid, when you’re genderqueer, when you’re making a statement, when you’re exploring, when you’re unsure where you’ll wind up, it makes sense to be cautious. Many of the bodily changes caused by hormones are not reversible, and surgery certainly isn’t. But I think people pretty much realize that.

I’d like to close by talking about our online identities and then briefly about the importance of preserving our history.

What has been concerning me lately is social identity and in particular our digital footprint. I could make similar arguments about other social networks, but I’m particularly annoyed by Facebook, so I’ll pick on it.

Is Facebook free? Is it? Well, you needn’t pay Facebook, but it and sites like it aren’t free. You pay with your economic data. These sites use sophisticated algorithms to data mine your actions and build a profile of you as a consumer; your profile, and those of millions of others, are sold to companies that would like to sell you a mortgage, or a cup of coffee, or a pair of jeans. You won’t see your economic profile, but it’s there, and it will stay there until you die, and even afterward. Facebook carefully preserves your economic metadata because it makes money for the company. Facebook doesn’t care so much about you or what you have to say.

Your Facebook posts aren’t private. You’re not anonymous. Your account is attached to your real name. Your posts are available for universities and potential employers and anyone else who wants to view them to see who you are and what you’ve had to say. You can control this by carefully managing your profile, but Facebook has a longstanding and annoying habit of changing its privacy settings and opting you out of the privacy level you’ve selected, making you once again vulnerable.

When I was twenty friends told me I would be voting Republican by the time I was forty. I’m still waiting for that to happen—but statistically, some of you will eventually become Republicans. When that happens your Facebook posts and your blogs and transition video logs and all those selfies will be there waiting for whoever wants to scope you out. Did you know colleges routinely search for posts and tweets that mention them? Ditto employers. If you’re blasting a school and its people it won’t go down well with the admissions committee, I tell you, and the company you’re hoping will hire you might decide you’re more trouble than you’re worth simply because you’re trans.

So what I would ask of you is to consider this. I know how heady this gender thing is. I know how proud you are, and rightfully so—but please take time to think things through. Consider how that thing you’re planning to put on Facebook will look in twenty or thirty years, when you’re in line for a job with a Fortune 500 company or you’re Googled by your neighbor. Consider that we—that you—have enemies out there who would like nothing better than to pop your balloon. Please protect yourself.

Now for a brief word on transgender history.

We’re living in a remarkable time. We have legal protections we’ve never had before. We can marry as we please in 15 states. We’re able to live openly as never before. We’ve shed much of the shame and guilt that hobbled us in the past. We have many supporters.

We’re extraordinarily fortunate to be alive at such a time. So consider: we owe it to those who will come after us to document and preserve what we’re doing and how we’re feeling.

This is happening with older technologies. Next spring will see the first ever conference on trans history, to be held at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. The university there and other places in North America like the University of Michigan and the LGBT Historical Society of California have large collections of trans-related material—but they consist mostly of written correspondence, newsletters, magazines, photographs, and videotapes and DVDs. No one has yet thought much about preserving our ephemeral existence on social networks. That part of my history—and probably the entirety of yours, if you’re under 25 years of age— is at risk. It scrolls away, disappearing off the top of our screens, and we don’t see it again. We lose our cell phone and the hundreds of photographs we’ve taken are gone forever because we didn’t save them to a hard drive or to the cloud. And what happens to your history when Plurk or Second Life or Twitter or Facebook or YouTube disappear because the company fails, or a social network decides your posts are old enough to purge or you forget your passwords?

Over lunch last week trans psychotherapist Moonhawk River Stone told me of the disappearance of a Yahoo group and all its data after the members hadn’t used the group for several months. The Yahoo group contained important discussions of a coterie that was collaborating on a book, and suddenly, it was all gone. After many attempts to get an answer from Yahoo about what had happened, Hawk was told inactive groups are simply deleted. Hawk is clearly aware of the risk we all face when our documents are online or in the cloud and will be talking about just that at the trans history conference next spring.

Your history is important. Your history. The history of each and every one of you. This an exciting time, but it’s so only because of what you are doing and saying. Each of you. Every one of you. You are our present, and you will soon be our history. I urge you to give some thought to making a record of your personal history and finding some way, some place to keep it safe.

Thank you.