Dismantling the Gender Binary (2015)

©2015 by Dallas Denny

Source: Denny, Dallas. (2015, 25 April). Dismantling the gender binary. Keynote at 9th Transgender Lives: The Intersection of Health and Law Conference, Farmington, CT. Topmost photo by Karen Marie

Dismantling the Gender Binary

By Dallas Denny

Keynote at Transgender Lives Conference

Farmington, CT, 25 April, 2015

Many in this room would like to see an end to the gender binary. Most of us don’t like the way it constrains us— and for that matter, many cisgendered people don’t like the way it constrains them.

It wasn’t always that way. We were once, like almost everyone else, blind to the binary, which meant we were locked into place within it. Those of us who felt most constrained had no choice but to stay on the side of the binary on which we found ourselves or move heaven and earth to move to the other side, begging others for help. We never realized we ourselves held the key to our identities and to our bodies.

For the next few minutes I’ll be highlighting a few milestones I feel were important to a huge and essential change in human consciousness.

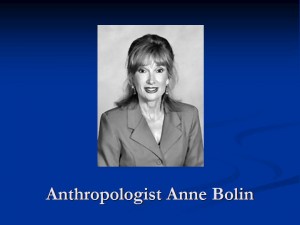

Today, when I look around this room I see what anthropologist Anne Bolin once called a splendor of gender. I see people of assorted ages, various races and ethnicities, various careers and avocations, and different levels of education, every one of whom has a unique gender identity and presentation. This includes the non-trans professionals and supporters and partners and family members here today, many of whom have been significantly impacted in their own beliefs and their own identities and presentations by the trans people in their lives.

I like that term. A splendor of gender.

It wasn’t always this way. When Anne did her doctoral dissertation, which focused on transwomen in a support organization in the Midwest, she found her subjects had limited identity choices. Actually, there were three: they could be crossdressers; they could be transsexual; or they could be female impersonators or drag queens. Each of these “career paths” had rigid role expectations and identity exploration of any sort was actively discouraged by the members. If you were a crossdresser it was heresy to experiment or even talk about experimenting with hormones. If you were transsexual you were encouraged to get on with your transition. (I once had a friend who was asked to leave her support group in Pittsburgh because she wasn’t moving forward quickly enough with her transition. It didn’t matter that she was indigent.)

Bolin was politicized by her work on gender variance. Her 1988 book In Search of Eve and many of her professional papers and presentations severely took to task the medical model of transsexualism, which I will talk about in a moment.

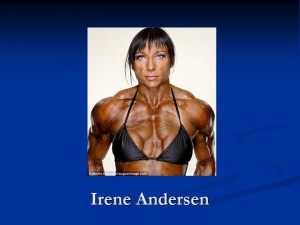

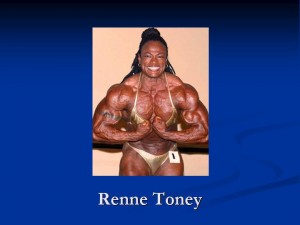

Anne was personally impacted by her work on gender variance, but surprisingly, not most directly by us. When she saw the 1985 film Pumping Iron II: The Women, she became fascinated with professional female bodybuilders—and especially with the ways in which they, like the transsexual women she had earlier studied, pushed the boundaries of gender expression.

Their muscled physiques, sometimes enhanced with anabolic steroids, resulted in bodies that were nontraditionally feminine and those bodies threatened the male-dominated bodybuilding world.

Despite efforts to feminize themselves with makeup and elaborate hairdos, there was a point in physical development beyond which early female bodybuilders were just not allowed to compete.

Anne was and remains fascinated by just such boundaries. In fact, she herself became a bodybuilder.

We trans people have always been on the boundaries. Today everyone knows who we are and we have many supporters and no shortage of enemies. We continue, by our very existence, to push limits, but once we were simply beyond the ken. We were unfathomable genderrevolutionaries in a society that had no notion it was even possible to question the construction of gender. We are where we are today because we have pushed and continue to push on the boundaries and especially because at some point we realized the problem was not with ourselves but with the gender binary that artificially constrains our appearance and behavior. But let me be clear—despite our gender presentations, despite our gender identities, we were, until only 25 years ago, just as trapped in the binary as everyone else.

Here are the milestones I promised you.

Shot One: Christine Jorgensen

The opening salvo of our war on the gender binary arguable came on December 2, 1952, when news of Christine Jorgensen’s “sex change” (as it was called) pushed news of the hydrogen bomb tests below the fold on the front page of the New York Times. My thanks to Susan Stryker for initially pointing that out.

Jorgensen was an ex-serviceman from the Bronx who, after reading about animal experiments with newly synthesized human sex hormones, contacted Danish endocrinologist Christian Hamburger and persuaded him to give her estrogen and surgeries to feminize her body. In other words, she was a social engineer who initiated her own treatment. After several years in Denmark, news of the procedures was leaked to the press and reporters and photographers were everywhere. Every television and radio station, every newspaper and magazine around the world carried the news.

Upon her return to the U.S. in early 1953, Jorgensen was mobbed by the media. You can see from the photo her presentation was that of a traditional 1950s American woman. That such an obviously feminine person had been born male blew the collective mind of the entire world.

Jorgensen is significant not only because of her courage and determination to live as a woman, but because the world was blindsided by her change of sex. Reporters, physicians, the general public, even other people we might consider transsexuals—had no notion sex could be changed. Sex was unitary and intractable and could be present in only two forms—male and female. Jorgensen was the world’s first real proof that simply wasn’t true. In a world of black telephones and white refrigerators—yes, it’s true, once upon a time all telephones were black and all refrigerators were white— Christine Jorgensen was a shade of gray.

Jorgensen is significant also because of her impact on others like her. She and her physicians received hundreds of letters from desperate men and women begging for similar treatment— which wasn’t available—and for every person who managed to mail a letter, there were thousands similarly affected who didn’t write. She was a role model, of course, but aside from that she provided the seeds for an identity that would soon be called transsexualism. This eventually led to medical and psychological procedures to allow transsexuals—some of us, anyway—to change sex, but which came with a horrible double cost—a diagnosis of mental illness and affirmation of the gender binary that stripped us of autonomy and led to horrible abuses at the hands of those who thought they were helping us.

I’d like to reaffirm: Jorgensen’s presentation was culturally normative for a female of her day. She successfully crossed the gender divide, but she merely moved from one binary box to another.

Shot 2: The Differentiation of Sex and Gender

In the 1950s the world saw sex as a single and apparently simple thing. There was one sex, there was the other, and that was it. Gender and sex were used interchangeably. But something interesting was happening at Johns Hopkins University in the labs of psychologist John Money. From his work with the intersexed, Money and physicians John and Joan Hampson developed a multivariate definition of sex. Sex, it seemed, wasn’t unitary at all. Rather, it had multiple components— genetic, chromosomal, hormonal, social, and identity-based— and any marker could be either male or female; for instance, gender identity could be male while other indicators were female. This multivariate definition of sex definitively differentiated sex from gender and worked well for both intersexed and trans* people.

Money is rightly reviled today because of his disgraceful and unethical behavior in the case of David Reimer, but his differentiation of sex and gender in the mid 1950s was key, for it provided the basis for the eventual undoing of the medical model of transsexualism that was about to be born.

Shot 3: The Birth of the Medical Model

Christine Jorgensen wasn’t the only one who understood the significance of sex hormones. Transman Michael Dillon, himself a physician, transitioned before World War II. In 1946 he published a book called Self in which he obliquely wrote about his testosterone treatment. And female impersonators around the world were telling one another about female hormones.

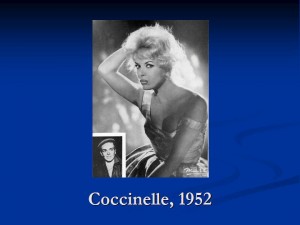

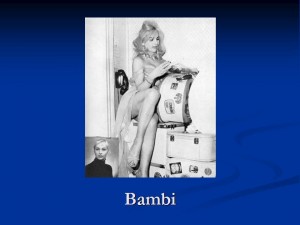

I realized this in 1992, when I bought a copy of the 1953 program book of Madame Arthur’s, a night club in the Pigalle district of Paris, I realized something was going on with some of the entertainers—and in particular with Coccinelle and Bambi.

It seemed apparent to me they had been on hormones for quite some time. Note the inset photos, which are supposed to show them in the male role. Neither look particularly male. These inset photos, by the way were traditional in nightclub program books and publicity posters of the day.

In her first autobiography, April Ashley affirmed what I had figured out. Ashley also noted transsexuals from the time were journeying to Casablanca for SRS with surgeon Georges Burou, about whom I spoke about earlier today.

In the U.S. transsexuals flocked to the New York and San Francisco offices of endocrinologist Harry Benjamin, who provided them with hormones.

Benjamin was sympathetic toward transsexuals and wished to convince his fellow physicians to provide them with treatment. To this end, he published, in 1966, his book The Transsexual Phenomenon, in which he defined a medical syndrome and argued for sex reassignment—in certain cases.

Benjamin’s book was firmly rooted in the gender binary, as evidenced by this chart, which is called the Benjamin Scale.

I’m not so sure Benjamin was himself a devotee of the binary. He was a man who sincerely cared about his transsexual patients, and I’m convinced the arguments he used in The Transsexual Phenomenon were the only ones he could have possibly put forth that would convince other physicians to provide treatment, but his book unfortunately became the basis for what I call the medical model of transsexualism. By that I mean it is presumed transsexuals are mentally ill and in anguish, and since they cannot be cured of their feelings the most humane thing to do (in certain instances) is to provide them with palliative medical and psychological treatments. These treatments will not cure them, but will provide psychological relief and leave them more fully functional in society. This, in a nutshell, is the medical model. It saddled us with a mental illness and usurped our right to make decisions about our own bodies, forcing us to be supplicant to the medical and psychological establishment. Again, I say, considering the times, this might have been necessary.

I find it ironic that Benjamin, who wished only to help us, inadvertently set into motion processes that caused a great deal of grief and perpetuated the binary gender system. I find it doubly ironic that considering the spirit of the times, the medical model might have been a necessary precursor to the freedom of self-definition we enjoy today.

In 1969 psychiatrist Richard Green and John Money published the edited text Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment, which established a treatment model for the syndrome Benjamin had introduced. Within ten years there were more than 40 university-based gender clinics in North America, all following this protocol.

I’m convinced the staff at the clinics for the most part meant us well, but the clinics reinforced the gender binary by requiring strict conformity to gender norms. Transsexuals were expected to dress and behave in sex-stereotypical ways and treatment was all or none. Most applicants were rejected, and those few who were accepted were expected to go all the way—i.e., cross-live, take hormones, and, finally, have what was then called sex reassignment surgery.

The clinics generated a body of “scientific” research literature based upon the heteronormative and sexist beliefs of their personnel and this research was used to define transsexuals, who were depicted in the pages of medical journals as hysterical, dishonest, and manipulative with personality and character disorders and any number of psychiatric co-diagnoses.

I was turned away by one of the gender clinics— the one at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. After taking my money they told me that because I had professional employment, because I had two college degrees, and because I had held my marriage together for six years, they would not help me— in other words, I wasn’t screwed up enough to be transsexual.

I took myself down the street to Vanderbilt’s medical library and spent several months reading the scientific literature. It echoed what I had been told. Transsexuals were sad and pathetic and flawed. I though maybe I wasn’t transsexual, but what else explained my desire to live as a woman? The experience politicized me.

In 1991 I published this analysis of the gender clinics in my journal Chrysalis Quarterly. It’s available free of charge on my website, so I will spend no more time today on the evils of the medical model.

Shot 4: The Closure of the Gender Clinics

Had the gender clinics endured we might all still today we living in the gender binary, might still, most of us be getting turned away, but in 1979 there was a coup of sorts at Johns Hopkins University. Newly-appointed Chair of Psychiatry Paul McHugh conspired with disillusioned Hopkins gender clinic director Jon Meyer to publish post-hoc data that purported to show “no objective advantage” to SRS in male-to-female transsexuals— he admitted this in an article in American Scholar in 1992. He and Meyer then held a series of press conferences, making sure the news made its way onto every newspaper, magazine page and every news and television radio news show on the planet. For nearly twenty years supposedly knowledgeable professionals would say, “Oh, yes, transsexualism. Didn’t Johns Hopkins prove surgery didn’t work?”

The immediate result of this charade was the closure of the clinic at Hopkins, and, because of Hopkins’ prestige (which had led dozens of universities to open their clinics in the first place) the remainder of the clinics soon closed as well. The ultimate result was transsexuals, who had been kept separate from one another because of confidentiality concerns, began to talk with one another and with nontranssexual transpeople; this soon gave rise to a community that evolved into the one we see here today.

Shot 5: Moving Beyond the Binary

The late 1980s saw the rise of an integrated trans community. Until then transsexuals had not organized to any significant extent—kudos to Marsha P. Johnson and Silvia Rivera and others for their early efforts—and the crossdressing community was under the firm control of the late Virginia Prince, whose organizations had a “no gays, no transsexuals” policy. Suddenly, at conferences like the Midwest’s Be-All and IFGE’s Coming Together, in the pages of hundreds of support group newsletters and a half-dozen or so magazines, and on computer bulletin boards, we were talking to one another, writing for one another, grappling with terminology, and realizing that in our efforts to conform to the existing identities of heterosexual crossdresser, transsexual, or drag queen/female impersonator, we had been untrue to ourselves.

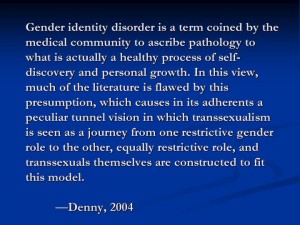

Although I didn’t write the following until 2004, the above slide is I think a good description of what I and others in the community were figuring out by the late 1980s.

In 1992 I published Holly Boswell’s article “The Transgender Alternative” in Chrysalis. It appeared simultaneously in IFGE’s Transgender Tapestry, a magazine I would one day edit.

To say it was a watershed essay would be an understatement, for it transformed the community. It opened our eyes to the limitations we were placing upon ourselves.

Holly simply pointed out different ways in which we could live without confining ourselves to strict binary interpretations of gender and the binary identities as crossdresser and transsexual. Her essay popularized the term transgender, which had until then been used only sporadically—but more than that, it provided non-transsexual-identified transpeople with the same kind of model Christine Jorgensen had once provided for transsexuals.

Within a year the term was being used widely and was appearing in the gay and mainstream press—and of course in the pages of the trans community’s many magazines and newsletters. Considering the internet was not yet in wide use, that’s a remarkably rapid change.

When Anne Bolin attended Southern Comfort in 1992 and 1993, she was amazed at the wealth of gender identities and presentations of the attendees. It was far different from what she had seen less than ten years earlier. She wrote about the change in her chapter in fellow anthropologist Gil Herdt’s book Third Sex, Third Gender.

And that did it. We had broken from the gender binary. As the years went by more and more of us came to have primary identities as transgender and we ranged further and further afield in our quests to define ourselves.

All this, and of course the internet, has led us to the diversity we see in this room today. For us, the change has been profound, but it has also been profound for the larger world. As I said, it represents a change of human consciousness.

Health Consequences

This is a health conference. What, you may wonder, does all this talk about the gender binary have to do with our health? Just this—under the medical model we were considered patients and access to medical treatment like hormones and surgery was limited. Psychologists and other counseling professionals had the say-so as to whether we got treatment—and many of us didn’t.

Today we can hardly imagine a health professional telling us who we are or who we can or cannot be or how we must dress and live our lives. Not that long ago, though, that was the reality.

We don’t know the fate of the tens of thousands who were turned away from the gender clinics. We don’t even know what happened to the minority who were accepted for treatment, for they were counseled by clinic staff to disassociate themselves from their pasts and blend into the binary society—and that’s just what they did.

Not only did the collapse of the medical model of transsexualism free us as individuals—it had a profound effect on the literature. In particular, it freed us from hypotheses based on a presumption of mental illness and opened the door to wellness-based and non-binary based hypotheses. Not only was there an explosion of gender expression and identity—the splendor of gender Anne Bolin wrote about—but there has been an explosion in research that has greatly increased not only our healthcare opportunities, but our legal standing and who we are as a community.

I’m proud to have been witness to this change.

Thank you.

Note

The most interesting comment made by the audience came from a woman who identifies as transgender and considers the term transsexual defamatory. In my reply I said I myself identify both as transgender and transsexual, and that transsexual seems to be well on its way toward obsolescence. I noted that my presentation was historical and I didn’t consider it most appropriate to use the terms in use during the period under discussion.

My audio recording failed, but I may be able to retrieve the conversation from the video recording.

References

Ashley, April, with Fallowfield, Duncan. (1983). April Ashley’s odyssey. London: Jonathan Cape.

Benjamin, H. (1966). The transsexual phenomenon: A scientific report on transsexualism and sex conversion in the human male and female. New York: Julian Press.

Bolin, A. (1988). In search of Eve: Transsexual rites of passage. South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, Inc.

Bolin, A.E. (1988). The splendor of gender: Socio-cultural contributions to gender variance. Plenary address at The Second Oklahoma Conference of the Society for the Scientific Study of Sex, 30 September-1 October.

Bolin, A.E. (1994). Transcending and transgendering: Male-to-female transsexuals, dichotomy, and diversity. In G. Herdt (Ed.), Third sex, third gender: Essays from anthropology and social history, pp. 447-485. New York: Zone Publishing.

Boswell, H. (1991-1992, Winter). The transgender alternative. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(2), 29-31.

Denny, D. (1992). The politics of diagnosis and a diagnosis of politics: The university-affiliated gender clinics, and how they failed to meet the needs of transsexual people. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(3), 9-20. Reprinted in Transgender Tapestry, Summer, 2002, 1(98), 17-27.

Denny, D. (2004). You make me sick!: A critique of the psychological and medical literature of transsexualism. Paper presented as part of the Trans-Progressing Symposium, Fantasia Fair, 17-24 October, 2004, Provincetown, MA.

Dillon, Michael. (1946). Self: A study in ethics and endocrinology. London: Heinemann.

Green, R., & Money, J. (Eds.). (1969). Transsexualism and sex reassignment. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

McHugh, P.R. (1992). Psychiatric misadventures. American Scholar, 61(4), 497-510.

Meyer, J.K., & Reter, D. (1979). Sex reassignment: Follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 36(9), 1010-1015.

Money, J., Hampson, J.L., & Hampson, J.G. (1955). An examination of some basic sexual concepts: The evidence of human hermaphroditism. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, 97, 301-319.

Money, J., Hampson, J.G., & Hampson, J.L. (1956). Sexual incongruities and psychopathology: The evidence of human hermaphroditism. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, 98, 43-57.