All We Were Allowed to Write (2014)

©2014 by Dallas Denny

Source: Denny, Dallas. (2014, 22 October). All we were allowed to write: Transsexual autobiographies in the late XXth and early XXIst centuries. Workshop presented at Fantasia Fair, Provincetown, MA, 19-26 October, 2014.

All We Were Allowed to Write

Transsexual Autobiographies in the

Late XXth and Early XXIst Centuries

Dallas Denny

Presented at Fantasia Fair 40, 22 October, 2014

Hello, and welcome. My name is Dallas Denny. I’m speaking today about transsexual autobiographies. Feel free to ask questions at any time.

I’d like to start by illustrating the difference between autobiographies and memoirs. In this talk I will not be making a distinction. I’ll use the term autobiography to refer to both.

Autobiographies focus on the trajectory of an entire life, starting at the beginning and progresses chronologically to the end. Autobiographies feel more like a historical document. There is a lot of fact checking and specific dates and information. Autiobiographies strive for factual, historical truths. They are typically written by famous people.

Memoirs focus on a key aspect, theme, event, or choice in a life. They can start anywhere and deftly move around in time and place. Memoirs feel more personal than autiographies and typically have less fact checking. They strive for emotional truths and can be written by anyone.

Before 1994 or so, transpeople were excluded from our own literature. We authored no textbooks and had no book chapters or articles in professional journals.

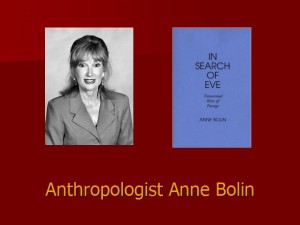

This exclusion was not voluntary. Anthropologist Anne Bolin, who is not trans, once told me a rejected peer-reviewed journal article was returned to her with a scrawled content on the cover, written by one of the reviewers: “Obviously a transsexual.” The subtext was and obviously, transsexuals have nothing of worth of say about transsexualism.” We were not allowed to contribute to our own literature.

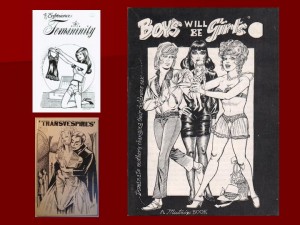

This doesn’t mean transpeople weren’t writing, of course, just that we weren’t being published. Trans nonfiction was pretty much limited to educating peers.

Crossdressers produced an astounding amount of pornography and stories about feminization. Fantasia Fair has acquired more than 800 of TV fiction books, including these, and has donated them to the transgender archive of the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada.

Here are some early transsexual autobiobiographies– and one biography.

What transpeople could get published, at least from the 1950s onward through 1990 or so, were autobiographies. Above is an early autobiography of what we might today call a transgender person. It was first published in 1918.

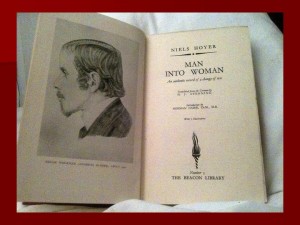

While not an autobiography, Niels Hoyer’ s Man into Woman was significant in that it recounted the life of Lili Elbe through her diary entries. The author’s actual name was Ernst Ludwig Hathorn Jacobson. He was a friend of Lili, who, before her death, asked him to tell her story. Man into Woman was published in 1933. This is the frontispiece and title page of the original English translation.

I used this photo of Elbe’s grave for the frontispiece of my 1994 book Gender Dysphoria: A Guide to Research.

Lili Elbe, for those who might not know, was a Danish painter born with the name Einar Wegener. Lili underwent a series of surgical procedures in Germany in the late 1920s and died as the result. David Halberstam’ s novel The Danish Girl is based on Lili’s relationship with her wife Gerta, who was also a painter, and whose evocative images of women (many of them based on Lili) are popular today.

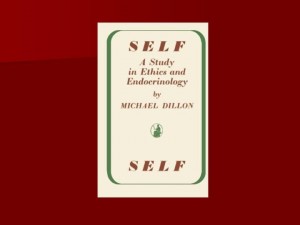

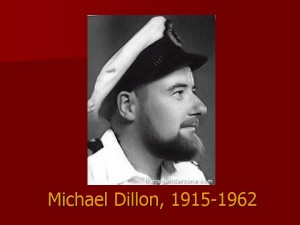

1946 saw the publication of his book by FTM Michael Dillon. In it, he obliquely mentions his transsexualism.

Dillon was born into the British aristocracy. He transitioned in the 1940s and had phalloplasty by the groundbreaking plastic surgeon Harold Gillies. Dillon was outed when someone noticed in the social register his parents had no son Michael. They had, however, had a daughter named Laura. Dillon became a captain in the Canadian navy and eventually a monk in Tibet.

When news of Christine Jorgensen’s sex reassignment in Denmark broke on 2 December, 1952, transsexuality as an identity and life path was born— even if the word was not yet in popular use.

Jorgensen didn’t write her autobiography until 1967.

And so it’s not surprising transsexual autobiographies soon began to appear. 1954 saw two by British citizens— Robert Allen’s But For the Grace and Roberta Cowell ‘s Story.

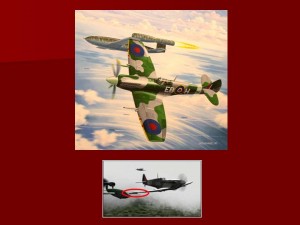

Robert Allen, born female, successfully petitioned to have his sex changed to male. He claimed he had no hormones or surgery. Before her transition, Roberta Cowell was a Spitfire fighter pilot during the Second World War.

In her book, Cowell writes of tipping Vi flying bombs with the wingtips of her Spitfire, turning them and sending them away from Britain and back toward Europe and the Nazis.

The V1 was an unmanned and unguided drone, powered by a kerosene-fueled jet engine. V1s were launched from aircraft or from the ground in coastal France and other locations, pointed in the direction of England with a load of fuel calculated to take them over London and military targets. When they ran out of fuel, they would fall to the ground and explode in more or less random locations.

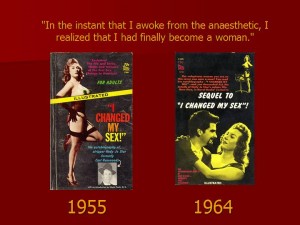

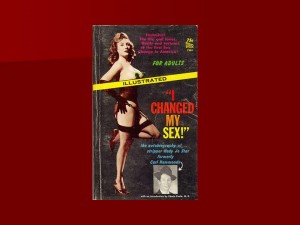

1955 brought Hedy Jo Star’s provocative I Changed My Sex. Star was born in 1920 and died in 1999.

Star was clearly capitalizing on the fame of Christine Jorgensen. Of the book, Sandy Stone wrote in her 1991 essay The Transsexual Empire Strikes Back, “Star’s book has disappeared from history, and I have been unable to find reference to it in any library catalog. Having held a copy in my hand, I am sorry I didn’t hold tighter.” I had a copy of my own. It is now held at the University of Michigan Library System.

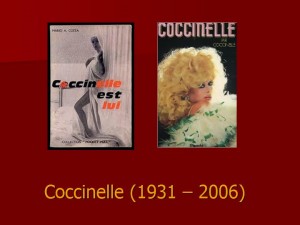

Hedy Jo Star wasn’t the only early male-to-female entertainer to tell her story. Mario Costa’s book Coccinelle was clearly thinly-disguised aubiography. It appeared in 1963. In it, Coccinelle accuses Brigitte Bardot of stealing her hairdo.

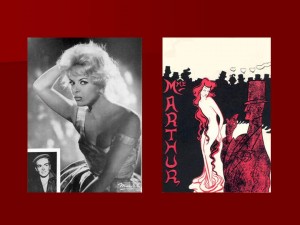

Jacqueline Charlotte Dufresnoy was her real name— Coccinelle, her stage name, is the French word for ladybug. She was a fixture of the nightclub scene in Paris’ Pigalle in the 1950s and was an actress and entertainer throughout her life. She was an activist for trans issues in her later years. This photo is from the 1953 program book for Madam Arthur’s cabaret, where she made her first public appearance. I bought the book for four dollars from a vendor back in 1992 or so at the second Southern Comfort conference.

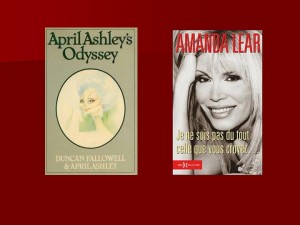

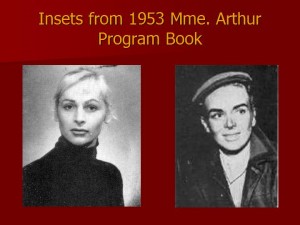

Two of Coccinelle’s contemporaries at Paris’ Mme. Arthur’s and Le Carrousel went on to write autobiographies of their own. April Ashley’s is jaw-droppingly name-dropping. Even today, Lear pretends she isn’t transsexual. She constantly embarrasses herself by changing origin stories in mid-stream.

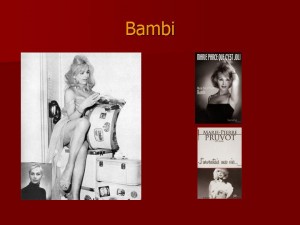

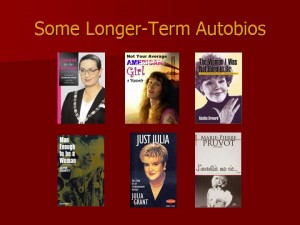

A third contemporary, Bambi, whose real name is Marie-Pierre Pruvot, and who, like Coccinelle, also appeared in several films, earned a master’s degree at Paris’ Le Sorbonne and became a high school teacher of some renown. She has written two autobiographies, one in 2003 and one in 2007.

Note the image at lower right in the page from the 1953 Mme. Arthur program book (left, above).

Images of entertainers in their “real” genders were common— in fact ubiquitous— through the end of the XXth century, and were typically placed as insets in program books and on show posters. In Bambi’s case, as in Cocinelle’s, what was the point?

By the way, that program book, and all the trans materials I collected, are housed at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and available for public viewing.

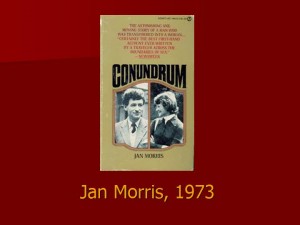

The 1970s saw the publication of several significant transsexual autobiographies. Jan Morris’ Conundrum appeared in 1973. Morris was and remains a well-known travel writer. She is best known for having accompanied Sir Edmund Hillary on his successful 1953 expedition to conquer Mount Everest. Morris has since written a second autobiography.

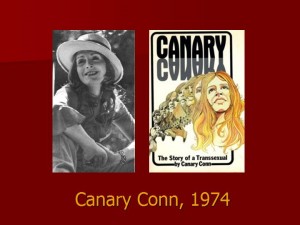

Canary Conn had some fame before transition when, as Danny O’Connor, she won a vocal contest and recorded four songs for Capitol Records.

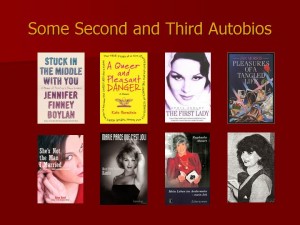

Renée Richards is an opthalmologist and amateur tennis player whose sex reassignment made national news. Although her autobiography didn’t appear until 1983, I’ve included her in the 1970s section because of the bouhaha which broke out when she was outed in 1976. Richards has since written a second autobiography.

Morris, Conn, and Richards were the visible face of transsexualism in the 1970s. Here are Morris and Conn holding court on the Dick Cavett Show, and Richards on court.

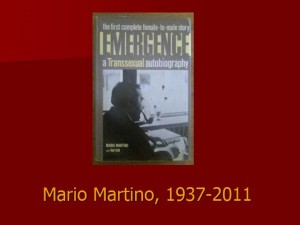

1979 saw the publication of Mario Martino’s Emergence. It was, so far as I know, the first modern FTM autobiography. Robert Allen’s denial of his transsexualism excludes him, so far as I am concerned.

At this point I’m going to switch from talking about the autobiographies themselves to my observations, and, in some cases, hypotheses— just some things I noticed. I’ve by no means read every trans autobiography, but I’ve certainly read more than 100 and I just acquired some 150 more. I think it would be useful to build a database of these biographies for additional analysis. In fact, it’s a doctoral dissertation in the making.

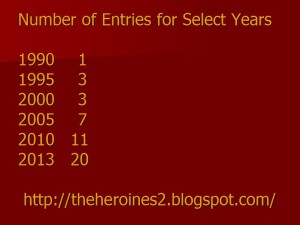

Trans autobiographies have been appearing at an astonishing rate in this century.

Since the 1980s they have increased in frequency in an exponential fashion. As a rough demonstration, here are the numbers of entries by year from the blog My Heroine’s Transgender Biography Books tab. The numbers represent only MTF autobiographies. There are more books by FTMs as well.

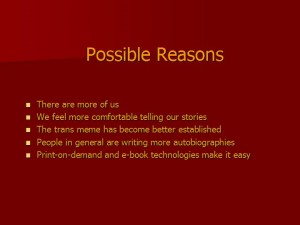

Why are there more autobiographies today? Above are some possible reasons. Who can think of more?

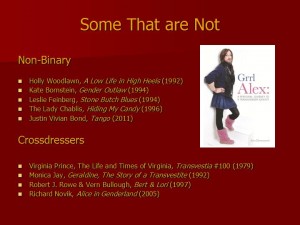

Autobiographies by crossdressers are not particularly common and we have yet to hear the stories of the majority of people who identify as genderqueer or third gender. As a result, most autobiographies are from people who have changed their sex- transsexuals, in other words.

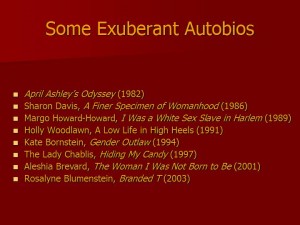

Above are some examples of autobiographies by nontranssexual transpeople. Holly Woodlawn was one of Andy Warhol’s “drag queens.” To Warhol, anyone born male who wore a dress was a drag queen. Of his three primary “drag queens,” I would characterize Candy Darling as transsexual, Jackie Curtis as a crossdresser, and Holly Woodlawn as a transgenderist. The defining moment in Holly’s autobiography, at least for me, was when her husband gave her money for sex reassignment surgery and she blew it in a huge shopping spree. Holly thought to be “proper,” she needed surgery. Only when she began to wonder why she had blown the money rather than have SRS did she realize she didn’t really want it.

Kate Bornstein’s Gender Outlaw is best characterized as a memoir rather than an autobiography. In it, she questions the gender binary.

Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues is a novel, but is clearly autobiographical. It was and remains quite popular. Leslie, like his character Jess, walked the line between genders.

As usual, when it comes to crossdressing, Virginia Prince was there first. She told her story in issue No. 100 of her magazine Transvestia.

I didn’t include The Transvestite Memoirs of the Abbe de Choisy on this slide because to me, it reads like transvestite fiction. I’m not convinced it’s authentic. The work dates to the late 17 century.

Autobiographies by female-to-male transsexuals are appearing in great numbers, but are small in comparison to MTF autobiographies.

Here are some autobiographical works by FTMs.

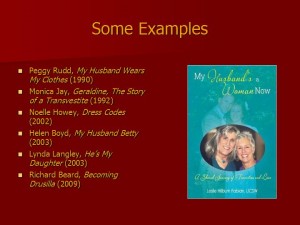

There are increasing numbers of titles from partners, children, and parents of transpeople. Over the next few years I expect a deluge of material from and about transkids.

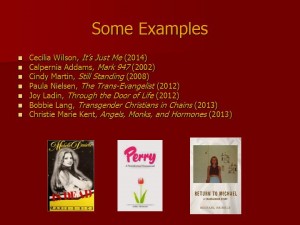

Many transsexuals struggle with their personal religious beliefs as it impacts their

transitions. Others struggle with repressive religious-based families and churches.

The three titles at the bottom were written by people who, after transition, returned to the male role due to religious conflicts.

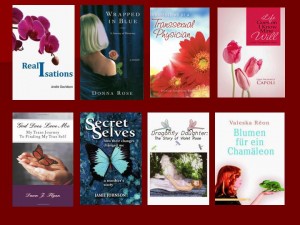

Many covers are allegories. Butterflies and flowers are common motifs.

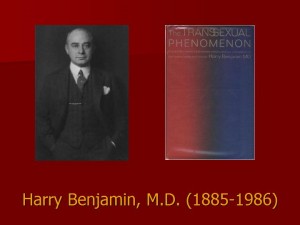

In his 1966 text The Transsexual Phenomenon, endocrinologist Harry Benjamin defined transsexualism as a syndrome defined by great internal pain. The treatment system that soon sprang up required transsexuals to convince physicians this pain was overwhelming. If they didn’t, they didn’t qualify for sex reassignment.

The pain is certainly real, but many transsexual autobiographies focus almost entirely upon it. I have called this the transsexual narrative. The transsexual narrative centers upon the struggles and pains leading to transition.

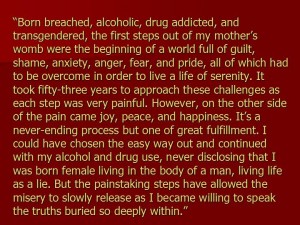

This description by the author pretty much exemplifies the transsexual narrative.

I think this narrative is the reason why so many transsexual autobiographies end immediately after surgery. Ten or so pages before the end of the book, the author is still in the assigned gender and in despair— in one book walking in the woods with a shotgun, contemplating suicide.

Several pages later he or she is post-op and it’s like a Disney movie. The reader is expected to believe that despite a life full of dysfunction and depression, all has been magically cured.

There are, happily, quite a few biographies which were published years or decades after transition. Christine Jorgensen, for instance, published her autobiography more than 15 years after her transition.

There are a surprising number of transwomen who have written second or even third autobiographies. The woman at lower right is Phoebe Smith of Atlanta. For many years she published the early groundbreaking magazine The Transsexual Voice. Her autobiography is impossible to find. Happily, she is working on a new autobiography.

My favorite autobiographies are the ones that manage not to be mired in pain and misery. My very favorite is a self-published book by a woman named Sharon Davies.

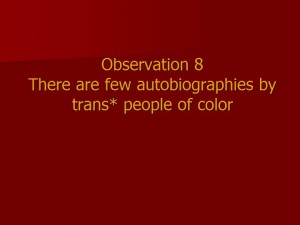

I can’t think of a single early autobiography by a transman or trans woman of color. fortunately, they have been appearing in this century. Janet Mock’s, in particular, is a best seller.

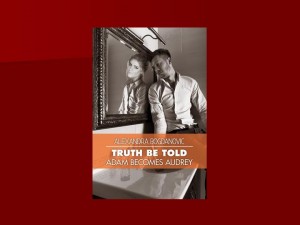

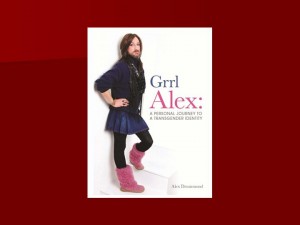

That’s it for my observations. I’ll close with assorted images of the covers of autobiographies. Please note the extraordinary themes and titles on many of the covers.

Those are but a few of the many trans autobiographies I have come across.

Thank you for your time.