Being Virtually Virtual (2011)

©2011 by Dallas Denny and Heather Kay Verdui

Sources:

Denny, D., & Verdui, H.K. (2011, 23 September). Virtually virtual: Gender performance in three-dimensional online worlds. Paper presented at Southern Comfort Conference, Atlanta, GA.

Denny D., & Verdui, H.K. (2011, 7 May). Virtually virtual: Gender in online worlds. TransEvent 2011: The Albany Conference, Albany, NY.

Note: Heather Verdui and I met in the online world Second Life in November, 2007. We were married in real life on March 23, 2015.

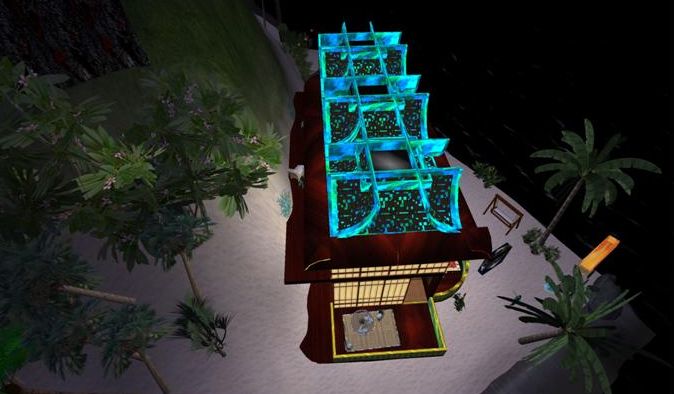

What you’re just seen is our three-dimensional playground. Just like any playground, it’s full of imagination, and silliness, and sometimes drama.

For more than four years now we’ve been lovers and partners in the virtual world Second Life– and in real life.

We find virtual worlds amazing, but we realize we’re in a minority.

The mere term causes brain freeze in some people.

The fact is, we all have a variety of personas that we wear like suits of armor. We’re husbands, wives, mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, aunts, uncles. We’re dedicated employees, patriotic citizens, members in good standing.

These are tied to our real bodies. But lots of things aren’t.

Second Life is where we met, and where we go to be together in very real ways when we’re hundreds of miles apart.

It’s a place where we can dance, or take a quiet ride in a sailboat or stand together on a beach and hear the same sounds— bird songs and crashing waves— a place where we can watch another couple grow larger as they approach us along the shoreline. It’s a place where we can watch movies while cuddling or go to an art opening or ride horses.

At the heart of every relationship there’s a secret language, a secret understanding that comes from spending time together, sharing experiences, playing together, and working together. We have that when we’re together. And when we’re not together, we have it in Second Life.

And while the setting may be virtual, the experience it provides is real enough.

So let’s talk about the difference between virtual reality and reality reality and why they’re not that different.

How many of you have ever participated in a virtual environment?

So, some of you think you have. Many of you think you haven’t. Remember your answer. We’ll revisit this.

Now we’re going to ask you another question.

How many of you consistently present yourself in different ways when your real life setting— at work as opposed to home, for example, or at church? You might even dress differently.

We know, we know, what a question to ask in THIS room!

Okay, can some one give us an example?

The fact is, we all have a variety of personae we wear like suits of armor. We’re husbands, wives, mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, aunts, uncles. We’re dedicated employees, patriotic citizens, members in good standing.

Usually those personas represent the reality of our lives, but sometimes not.

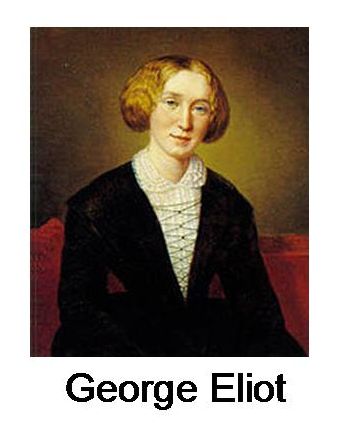

When authors use a pen name, they are creating a virtual persona. When actors play a role they are creating a virtual person.

This is British author Mary Anne Evans, who wrote under the pen name— persona— of George Eliot. Because she wanted to be taken seriously, she wanted people to presume her male. She had her reasons, but she was deliberately being deceptive.

Virtual reality. The mere term causes brain freeze in some people.And yet many of you have virtual personae you use daily, and which you find useful and comfortable.

Where? Have you ever used e-mail or joined an online group? Have you ever played an online game like World of Warcraft? Have you ever posted photos on FLICKR or used a social network like Facebook, LinkedIn, or Twitter?

When you create your account and select a user name, you’re creating a virtual persona.

In all these cases you interact with people who aren’t in the same place as you. You’re not seeing the same things (except the screen), not hearing the same sounds. Often, you’ve never met and will never meet them.But in a way they know you and in a way you know them.

How? By your interactions. Interactions with your actual self? No. By interactions of your virtual selves.

So whether you realized it or not, you’re virtual.

And not only is it virtual, we maintain it’s far more contrived, more artificial than what we do in our special playground— Second Life.

What do we mean by that? Let’s look at Facebook. Facebook is an absurdly popular social media website.

On Facebook you construct a virtual persona, a one-dimensional representation of yourself. People know you how?

By your name, by a tiny icon, by snippets of text that identify you by birthday, location, relationship status, and interests.

Because that’s doesn’t really say much about you, you can fill out forms to indicate your interests: favorite movies, books, television shows, likes and dislikes. They flesh out a rather skimpy picture of you. You construct your profile to represent aspects of yourself you want others to see.

To use Facebook, you must learn a new way of interacting. You post text messages on your “wall.” If you’re lucky, your friends will comment on your message. If your friends are lucky, you’ll comment on their status.

Replies come in slowly, usually hours after you post, for this is not a real-time medium.

To supplement this mundane means of communication, Facebook has added contrivances like pokes and likes. But for all this, our Facebook profiles don’t don’t say all that much about who we are.

It’s not all that exciting to look at text and the occasional picture.

But of course there’s Farmville.

Farmville is one of many attempts to spice up Facebook.

We find Facebook, boring, unnatural, and slow.

And yet millions of people have formed relationships there, and cherish them. For instance, it’s Heather’s father’s primary tool for his relationship with his teenaged granddaughter across the country.

Some of our online relationships take place in real time.

The free online video service Skype and similar programs let people actually talk to one another. Webcams send live streaming images to friends, provided you’re at your computer. And smartphones are Dick Tracy’s 1950s wristwatch television come to life. You can capture and immediately transmit video.

Of course, some people are uncomfortable with images of themselves on webcams and cell phones. Why? They’re more invasive of personal space.

How do I look? I can’t be seen like this! If I take this Skype call I’ll have to turn off the TV and this is my favorite show.

How many of you have formed personal relationships online— whether co-workers, buddies, sweethearts, or getting in touch with old friends?

How many have met people face-to-face they first met online, like co-workers from another location? How was the experience?

And that brings up the matter of identity. E-mail, social media sites like Facebook, and voice and webcams are tied to our real selves, the identities on our birth certificates and social security cards. Provable identities.

The underlying assumption when you use these media is the names, images, and personal information we share reveals details about who we actually are.

And letting people into our real lives can be dangerous. Even if the window into our lives is a narrow one, we must be concerned with issues of privacy, safety, and security.

So these are our two-dimensional personae. They’re plagued by narrow bandwidth, security concerns, and a clunky interface, and they’re tied to our real selves.

And they’re useful for work, for connecting with friends and family, for looking up high school friends, for sharing photos. People like and use them.

In our playground, identity isn’t pinned to your social security card. You create an identity from scratch. The real person is the avatar, and not the typist, and the company and the culture support that. You can share personal information, but most people don’t. It’s considered rude to even ask.

So. No tie to your real identity. A realistic expectation of privacy. And with the ability on your own to mute, ban, and report people who bother or harass you, there’s freedom to explore. You can look into issues of gender or sexuality. You can engage in social situations that would be difficult or impossible in real life. People with disabilities are able-bodied in our playground. Real life income isn’t important. Race isn’t important. Age isn’t important (although you must be 16 years old to enter). Looks don’t matter.

It’s safe space. Safe space for personal exploration and growth, a safe place to try things you haven’t or daren’t in real life. It’s safe to exercise your imagination, which is no doubt why our playground is filled with artists, writers, amateur sex workers, furries, vampires, and cyberpunks, and with every sort of fantastical content from rocket ships to Medieval fortresses

Our playground is colorful, three-dimensional, the size of Rhode Island, with voice, chat, IMs and body movement in real time, with sounds, and full of detail. You can take any form you want and have a perfectly normal time while doing it.

Interaction here is far more intuitive than with two-dimensional interfaces. Here, we see Bob and Bob sees us. We walk over and say hi, and to be polite he faces us and says hello back. When we walk into an art gallery we see the same paintings, the same people. When we ride a roller coaster we hear the same clunks and groans and the screamable moment comes at the same time.

Personal interactions in our playground are based on the real world. You know how to sit at a table and play cards with one another. You know how to chat at a party.

What’s most remarkable about this world is that there is no grand plan. It’s not an art designer’s idea of what virtual space should look like. We’re not limited by some corporation’s idea of what the world should be. We’re free.

There’s no scenario or script that tells us what we can or can’t do or be. There are no external goals. It’s not a game, it’s a world. We can do or be anything we can imagine.

In our playground, people socialize in real time, in three dimensions, surrounded by intricately-made objects and lush textures.

Every beautiful beach, every postapocalyptic city, every house, every stick of furniture, every item of clothing, the fairy wings and peppermint sticks— all were created by the inhabitants, by ordinary people like you and like us. Someone made this aggressive hummingbird. The walkway, the bridge, the mountain in the distance, our hairdos, the plants, the very skin we wear. Everything was created by someone.

Most of the people you saw in the film were us.

Most of the scenes were shot on Whimsy, our home, which we created in its entirety.

We took all the snapshots.

And snapshots are but a moment frozen in time.

Still pictures don’t capture the sound, the movement, the interaction, the three-dimensionness of our playground.

In this interactive private world it’s possible to represent yourself in almost any way imaginable.

What do we mean by that? You can be animal, vegetable or mineral. You can take the form of a dragon or the Goodyear blimp or a robot or a flying book. Check out the boxbots. Each one is a real person somewhere in the world.

You can be young and thin and beautiful and fashionable.

Or not.

You can easily play a cross-gendered avatar. In fact, in our playground many people play the other sex authentically.

Or you can be deliberately androgynous.

And it’s all fluid. You can change any aspect of your avatar at any time, instantly and without repercussion. You can easily go from male to female to dragon and back again.

You can imagine how comfortable this can be for GLBT people.

In our playground we can live authentic lives as a member of the target gender. Visually passing isn’t a problem (although voice can be). You don’t have to spend large sums on a wardrobe (although you certainly can!). You don’t have to spend hours getting dressed or drive an hour to go to a club or support group meeting. You just sit down and log in.

This brings us to our specific topic: relationships in virtual worlds.

In our playground you can get to know a person in a way that is intense and real…

…not just by his or her text replies to an e-mail or Facebook post, but by watching them interact with others. When people can present themselves in any possible way, their choices say something about them. How do they treat the waiter? How do they decorate their house? What clothes do they prefer? How do they act under pressure? Do they remember your birthday? Are they reliable? Honorable? Seductive? How’s their sense of humor?

In our playground you can share experiences and become intimate without ever meeting face-to-face or jeopardizing your safety in real life. It’s a rich place for relationships.

It’s where we met four-and-a-half years ago. Right here, when Cheyenne discovered Exuberance building this reflecting pool.

Why were we in Second Life?

For Heather, it was safe space after a horribly abusive marriage.

For Dallas, it was peaceful space after a lifetime of activism.

Cheyenne (Dallas)— was flying around looking at land parcels, hoping to buy and saw a woman on a hillside. Xubi— that’s Exuberance’s nickname— was making this beautiful fountain. We chatted and became friends (which is an official thing in our playground), but it was just the first stage of an acquaintanceship, a random meeting.

Later, Xubi contracted to build this house for Chey’s new parcel.

Chey had the opportunity to watch Xubi work while handicapped with an ancient Macintosh computer and Xubi saw how Cheyenne reacted when she (Cheyenne) accidentally wiped out terrain that had taken her a week to build— not once, not twice, but three times.

Our relationship developed slowly. Why? Because we were authentic with one another.

First, as we worked together on a house and land that was beginning to feel not like Cheyenne’s but like both of ours, our friendship deepened.

Eventually, there was a romance.

That required disclosure on Dallas’ part. She was utterly comfortable telling others about her transsexualism in real life, but with Xubi, in our playground, it was the hardest thing she ever did.

Fortunately, Xubi took it better than well.

When two people are being fully themselves the chance of a successful relationship is increased. We were ourselves, and we got past issues of gender, age, and distance. We developed a rich creative life full of friends, ridiculous projects, and shared memories, which Chey documents in her blog.

When we can’t be together in real life, we can have a rich social, intellectual, and emotional life in our playground.

We created Whimsy, the tropical archipelago we call home.

Our most ambitious enterprise was a robot sanatorium, a home for the many mentally malfunctioning mechanoids of the Metaverse.

Our projects give us a rich intellectual life and have taught us how to function as a team, with Xubi as the muse and Chey as the musee.

But what has it given us personally?

Well, it has given us each other. We seem pretty well matched.

Together, it’s truly is a place where we have learned to fly.