Creating Community: A History of Early Transgender Support in Atlanta (2015)

©2015 by Dallas Denny

Source: Denny, Dallas. (2015, 29 October). Creating community: An early history of transgender support in Atlanta. Workshop at Inaugural Peach State Conference, 29-31 October, Atlanta, GA.

Creating Community

An Early History of Transgender Support in Atlanta

Presented at Peach State Conference

31 October, 2015

By Dallas Denny

So, five facts about me:

My birth name was Dallas. Even though the prostitute in the John Wayne movie Stagecoach was named Dallas, I didn’t realize Dallas worked just fine as a woman’s name. Duh. When I would go out as a young girl I would make up a name, tell someone, and immediately forget it.

I lived in France for more than four years, from ages 6-11. I speak little French. Je suis desolée.

I bought my first computer in 1981, a Commodore VIC-20. It was so new there was no software and there were no storage devices available for it. That made it essentially a doorstop, so I learned to program using the built-in BASIC language. Every time I turned the computer off I would lose my work.

I always told people I would never live in Atlanta, Kansas, or New Jersey. When I transitioned in 1989 I had to go where the support was—Atlanta. I lived here for 26 years. In January I moved to New Jersey and got married. Am I concerned about Kansas? Yes.

As an activist I have always stayed on topic and made it about the issue and not about me. I do the work I do because it needs to be done and not for reward or acknowledgement—so of course doing the work has brought me both. Earlier this month I was talking on the phone with a nurse from United Health Care. She asked, “Are you the Dallas Denny?” I said I was and I added this introduction to this workshop so that will never happen again.

Today I’m going to talk about the early history of transpeople in Atlanta. If I get something wrong, if I omit something or somebody, or if you would like to add something, please, please speak up.

Okay. So to begin I’d like to hear from you all the names of any trans or trans-friendly groups or organizations with which you are or have been associated—especially those that are Atlanta-based.

(Eight or nine names were mentioned by the audience).

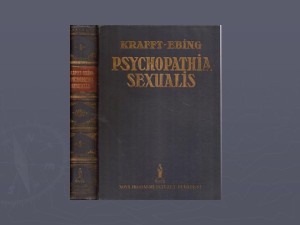

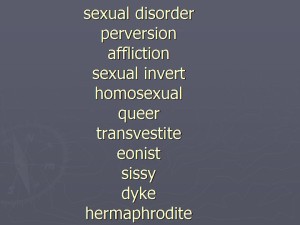

Now let’s suppose you are a young person in Atlanta in 1950 or 1940 or 1930 or even earlier. You have these… feelings you have no name for. How would you get information? How would you get support? Where would you look? What terms would you know? How would you classify yourself? How would you identify? How would you find or create community? About the best you could do would be to try to find a book that explained things or write off for information or confide in an authority figure or try to find someone like you.

Anyone know what this is?

If you were lucky enough to find something in the library, it would probably be something like this.

Maybe you would go to an adult bookstore and sort through the pornography in hopes of finding something informative. None of it would be easy.

A Home in the Gay Community

Like New York, San Francisco and other big cities, Atlanta has long been an economic and cultural center and as such has attracted people of all types. Among those were a considerable number of gender-variant people. But once here, where to go? Where to work? Where to socialize?

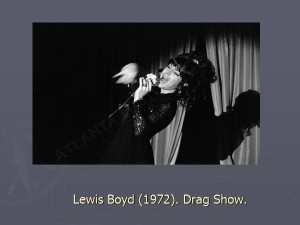

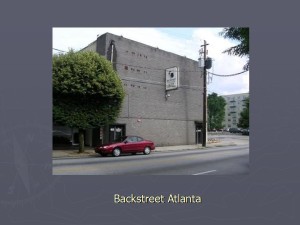

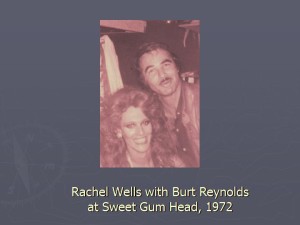

In Atlanta, as elsewhere, gay and lesbian communities organized long before trans communities—but gay men and lesbians were trying to figure themselves out and normalize themselves and many were hostile towards those who were gender-variant. Still, though, the clubs were safe havens and they became homes for many of us. Considerable number of gender-variant people worked in Atlanta as female or occasionally male impersonators. They worked at clubs like Sweet Gum Head on Cheshire Bridge Road, Peaches Back Door, Illusions, Cruise Head, Lavitas/Lipstix, Club 688, and Backstreet.

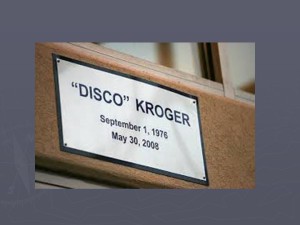

The Limelight was located in a shopping center at Peachtree and Piedmont. The nearby 24-hour grocery store soon became known as the Disco Kroger.

My knowledge of the early female and male impersonators is limited, but here are some well-known entertainers active in the second half of the twentieth century. Many are still around.

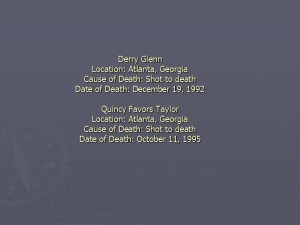

Some, unfortunately, are not.

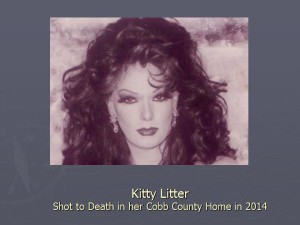

In 2014, Kitty Litter was shot to death by her partner in her Cobb County home.

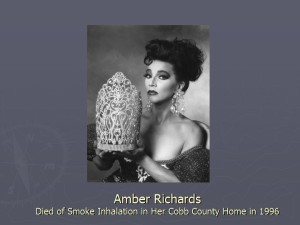

Amber Richards died of smoke inhalation when her Cobb County house caught on fire in 1996.

Many entertainers were people of color.

According to historian James Sears, black gay clubs included:

- The Marquette, on MLK Boulevard. It was the oldest.

- Lorettas, on Peachtree near the Margaret Mitchell house, was the largest.

- There were drag shows at Festival.

- Fosters was the seediest of the black clubs.

Some of the entertainers I mentioned identified as gay; that was common in the day. Nowdays a lot of drag performers identify as trans—but many don’t.

However they identified, established impersonators often served as big sisters or mothers of sorts for young people. They would coach them in dress and makeup and stage performance, get them gigs, direct them to doctors who would give them hormones, and, all too often, convince them to fill their bodies with silicone.

Here are a couple of well-known people who found a home in the club scene in Atlanta. This is a photo of punk rocker Jayne County. In her autobiography she talks about her salad days in Atlanta.

Ru Paul Charles lived and worked in Atlanta also.

The Birth of Atlanta’s Trans Community

In 1966 Maryland’s prestigious Johns Hopkins University announced the opening of a gender identity clinic for the treatment of transsexualism. After rigorous screening, only a few patients would be accepted.

Such was the reputation of Johns Hopkins that within a few years there were as many as 40 clinics in the United States—in New York, Minnesota, Michigan, Virginia, Los Angeles, Palo Alto, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Florida—and yes, Georgia.

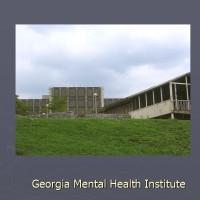

This is a picture of the derelict building that was the Georgia Mental Health Institute. It stood close to Emory University, and, with Emory, ran a gender clinic that provided hormones and surgery for a select few transsexuals. It was perhaps the first transgender-specific service or support organization for transpeople in Atlanta.

All was well for a time, but when the front page of the Sunday Atlanta Journal and Consitution announced the use of federal dollars by the Georgia Department of Vocational Rehabilitation to fund two male-to-female sex reassignment surgeries, the clinic was in trouble. It eventually closed. This was actually a good thing, for it spurred the development of peer support in Atlanta.

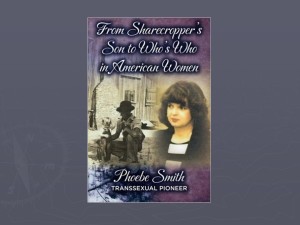

Phoebe Smith desperately sought help in Georgia throughout the 1960s, but found none. She eventually went to Mexico for GRS. Afterwards she became an employee of the state of Georgia and worked for the state until she retired in 2000. For several decades she quietly produced a monthly newsletter called The Transsexual Voice. With the Louisiana-based Erickson foundation no longer in operation, Phoebe’s Transsexual Voice was so far as I know for many years the only peer-produced transsexual-specific support publication in the world. Phoebe produced the last issue in 1995. It was an astonishing run, and helped thousands of people.

In 1979 Phoebe self-published an autobiography that is today nearly impossible to find. My copy now resides at the University of Michigan and that’s a long damn way to have to go to look at it.

Happily, however, Phoebe has written a new autobiography which is available on Amazon.com. The Kindle version is only $3.99 and is free to read with a Prime subscription.

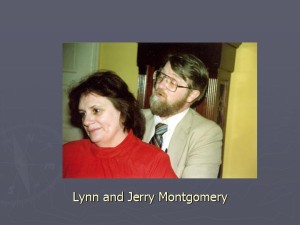

Lynn Montgomery was a nurse at GMHI in the days of the gender clinic. She eventually married transman Jerry Montgomery and together they started The Montgomery Medical and Psychological Institute. It was, despite the name, a support group. They helped hundreds of people, including me..

The Montgomery Institute published a newsletter, identified and trained supportive professionals and cultivated ties to the gay and lesbian community which set the stage for remarkable inclusivity in Atlanta in later years.

Lynn and Jerry were firm believers in the birth defect model of transsexualism. They considered the people who graduated from the group cured of an affliction, free to live a “normal” life. They eventually moved to Alabama and their institute moved with them. I have been told Lynn, who suffered from chronic fatigue syndrome, eventually passed away; I don’t know the year. Jerry now lives on the west coast.

I made my entry in early 1989. While living in Tennessee, I chanced across a copy of IFGE’s TV-TS Tapestry magazine and saw a listing for a TS support group in Atlanta. It was exactly what I had been searching for—for years.

I phoned daily for several months, at all hours. I left message after message, but none were returned. Finally, someone answered the phone. It was Lynn and Jerry’s nephew, Scott. Several weeks later I drove to Atlanta for an intake interview and my first support group meeting.

Lynn and Jerry were so impressed with my professional credentials that they drafted me to head their institute. All I came looking for was information to help me with my transition, but they sweetened the pot until I said yes. I moved to Atlanta in December, 1989 with a place to stay, a part-time job, and a cadre of new friends.

It was a heady time. For the first time transsexuals in the U.S. were talking to one another, and transsexuals and crossdressers were talking to one another and writing about ourselves—this thanks to Tapestry and a variety of newsletters. In early 1990 Lynn and Jerry flew to Colorado for the IFGE convention, where they told me, they met Christine Jorgensen (they couldn’t have, since Jorsensen died in 1989. I wonder who they DID meet). I stayed in Atlanta because I was lucky beyond my wildest imagining—I had found a full-time professional job as a behavior specialist. I worked for DeKalb County until I retired in 2009.

By mid-1990 there was tension between me and the Montgomeries. I moved out of their house and launched the nonprofit American Educational Gender Information Service and launched the groundbreaking publication Chrysalis Quarterly.

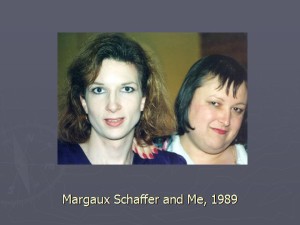

Graphic artist Margaux Schaffer created a corporate identity package for AEGIS and a design for Chrysalis.

When Lynn told me I was no longer welcome at the Montgomery support group meetings I founded the Atlanta Gender Explorations support group, which I am happy to say is still in existence; many members and former members are attending this conference. AEGIS provided information to transsexuals, their families, the media, and helping professionals, and published a magazine, booklets, and pamphlets. I was director until 2000, when AEGIS relaunched as Gender Education & Advocacy.

The Society for the Second Self is an organization for heterosexual crossdressers; in one form or another, it has been around since the 1960s. The Sigma Epsilon Chapter, hesitant to risk exposure of its mostly Atlanta-based members, had been meeting on alternate months in Chattanooga, Tennessee and Charlotte, North Carolina. In late 1989 or early 1990 the chapter began to meet in Atlanta. Under the leadership of Linda Peacock, who, despite the exotic name, was the wife of a crossdresser, the weekend-long meetings were open to transpeople of every stripe. Just about everyone in Atlanta dropped by at one time or another to chat or have dinner. Remember: in those days there was no place else to go except the drag bars.

The openness continued until about 1993, when a new leader enforced Tri-Ess National’s xenophobic no-gays no-transsexuals rule. Sigma Epsilon is still in existence, and still closed and closeted—but during the brief time the group was open and affirming, there was a synergy and sense of cooperation and kinship here in Atlanta that would soon lead to the Southern Comfort Conference.

The impetus for SCC came from Sabrina Marcus, who, on a trip to Boston, asked the International Foundation for Gender Education to start a trans conference in the South. IFGE said no, but agreed to send a team to Atlanta to show we locals how to put one together. True to their word, in the early fall of 1990 IFGE’s Merissa Sherrill Lynn and Yvonne Cook-Riley flew to Atlanta and met with representatives from every group in the South at the La Quinta Inn on Piedmont. There were representatives from, among others, AEGIS, AGE, Sigma Epsilon, The Montgomery Foundation, Asheville’s Phoenix Transgender Support Group, and groups from Florida, Virginia, Louisiana, and as far away as Texas. This consortium planned and held the first SCC; afterward SCC was its own entity.

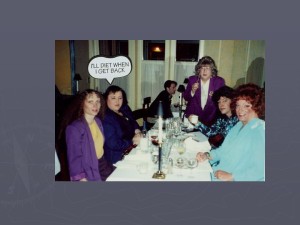

I was so busy throughout the 1990s I didn’t take many photos. Alas, I have none from that historic first SCC meeting. I did manage to find this photo of a dinner at the IFGE conference in 1992. That’s Holly Boswell to my right. Alison Laing is standing. Melissa Foster, who attended many SCCs and other conferences, is at the right front.

Here’s my only photo from the first SCC. In the picture with me is Yvonne Cook-Riley, Eve Burchert, Renee Chevalier, and other IFGE luminaries.

Other Atlanta groups formed as the 1990s rolled by—for instance the political group Trans=Action and LaGender, which was started by black transwoman DeeDee Chamble. Perhaps someone will take the reins from me and continue this history from the mid-1990s into the twenty-first century.

Relationships with Atlanta’s LGB Community

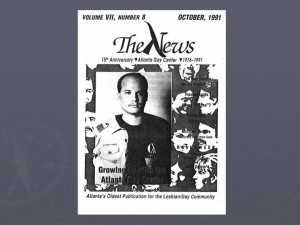

Lynn and Jerry Montgomery’s 1980s liaisons with Atlanta’s gay and lesbian community paid off in the 90s. We received positive coverage in the LGB media, and we were welcome at Pride. AGE had a booth most years and I served on the board from 1994-1996. The Atlanta Gay Center published a number of articles I wrote to further educate LGB people about trans issues.

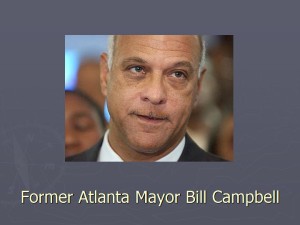

I also served on LGBT advisory board of Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell, who one day announced to us he had instructed the city council to adopt a transgender nondiscrimination bill. This duly came to pass. DeKalb County schools (my home county) announced a transgender nondiscrimination policy. Soon, the county had an overarching nondiscrimination policy.

Atlanta trans activists had not gotten around to initiating or even asking for any of this; it had all happened spontaneously, originated by Atlanta and DeKalb’s governments. Meanwhile, in other parts of the country, trans activists were battling furiously for their rights. It made me, truth to tell, a little ashamed, so I flagged down Al Fowler, the major of tiny Pine Lake in Dekalb County, where I lived, and asked him whether my city of 800 had a nondiscrimination ordinance.

“I think so,” he said. “Give me a day or so to find it.” Sure enough, two days later he sent me the ordinance. Damn! Foiled again!

Not All Sweetness and Light

Despite our advances, all was not sweetness and light in Atlanta. In 1993, Cobb County, to the north of Atlanta, passed an anti-gay ordinance. Three years later the Olympic Committee stopped the eternal torch at the county line and drove it to the Fulton County line in a windowless van.

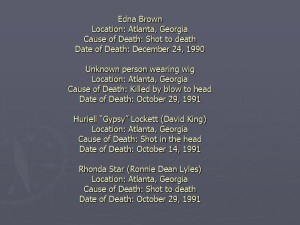

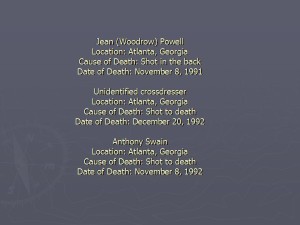

Far worse than the political posturing of buffoons from the northern suburbs, trans women were being murdered— are least twelve, and probably more. When I first arrived in Atlanta I would see small notices in the Journal/Consitution and in the gay papers noting the discovery of bodies discarded along the interstates. They were unfailingly identified as males wearing female attire. Many were sex workers, but not all. Some were popular and had jobs. Several were never identified. Not surprisingly, they were all trans women of color. Before long I was appearing on local TV after every grisly discovery, charging the police with recognizing there was an Atlanta serial killer of transwomen of color. They never admitted to it.

What follows isn’t a complete list. These are names I collected during my early years in Atlanta. Later, I gave the names to Gwendolyn Smith when she was began the Remembering Our Dead website. I’m sure I missed many more such notices, for they were small, just an inch or two in one column in the back pages of newspapers, and easy to overlook.

So, on this grim note I close this talk. It’s 1993 or 1994. Things are looking up for transpeople in Atlanta, but things are still very bad for us. I suppose I could say the same about 2015.

Thank you.