Clark in Three Parts (1991)

©1991, 2013 by Dallas Denny

In 1991, in the pages of the Stone Mountain Computer Users Group newsletter, I told the story of my work with a physically disabled man I called Clark.

Click the Tabs to Open

Clark: Part I: July, 1991

Source: Dallas Denny. (1991, July). Clark: A Reminiscence, Part 1. Newsletter of the Commodore Users Group of Atlanta, V. 9, No. 7, p. 2.

Clark: A Reminiscence—Part 1

By Dallas Denny

Note: I couldn’t possibly have done my work with Clark without the help of Wendy McAmis and Joyce Moore, who worked with him every day for ten years. Wendy was Clark’s program coordinator, and went above and beyond the call of duty to make sure his computer was “on line.” Joyce is a speech therapist, and trained Clark not only to use the computer, but in basic language skills as well. They are warm and caring people, and I cannot say enough good about them.

Last month, at the Commodore Users Group of Atlanta Executive Committee, we were trying to pick a topic for the upcoming main membership meeting. CUGA having been around for a long time, we’ve done just about everything at least once. I had what I thought was a not particularly good idea—Nostalgia and Brag Night. Members would bring in obsolete equipment and explain why it was once important, and would show off old programs or tell about their peak experiences with Commodore computers. The idea having been thrown out and duly accepted by the board, I hoped it would work.

Despite my misgivings, the meeting turned out to be one of our better ones. I told the following story, which Newsletter Editor Gene Smith asked me to put onto paper.

All my adult life, I have worked with people with mental retardation, in residential centers. In those centers there are a few men and women who are not retarded. They are there because their bodies have betrayed them. They cannot control their arms and legs, and in may cases, they do not even have enough motor control to talk—although they know how, and have much to say.

Clark was such a man. In his early fifties, he had a quiet dignity. Although his life must have been tremendously frustrating, he bore his physical burden with good humor and resignation. He would help feed and clothe himself as best he could, and would patiently try to force his mouth to say the things he wanted to say.

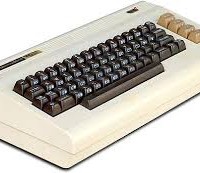

At the time, there were commercially available augmentative speech devices, but they were very expensive, and Clark, with his limited income, could not afford one. As it was 1982 or 1983, and VIC-20s were plentiful and cheap—and powerful, for the time—it occurred to me that a $49 computer with a tape drive would do just as much as a $1700 dedicated speech device—and Briarwood Cottage, where Clark lived, happened to have a VIC. I set out to write a program to help Clark speak.

I called the program Six Bits, because it took six presses of a digital switch (six bits of information) to select a single character from a field of 64. Sixty-four characters were enough to give Clark the letters of the alphabet and the numbers, punctuation marks, and even an electronic alarm, which would summon help.

I sacrificed a joystick, cutting off the cord, fitting the ground sire and the wire for the fire button into a Radio Shack jack. Clark used a custom-made foot switch. He would position himself in his wheelchair, and work the switch with his foot. It took him all his concentration and control, for he had to make the selection within a window of time (which was adjustable). Six presses, and the letter selected would appear on the screen. He could erase mistakes, or the whole message (he had to confirm to erase), and could save a message in memory while he worked on a second. When a message was complete, he could route it to the printer, or to a Votrax speech synthesizer, or just leave it on the screen for an attendant to read.

It turned out Clark had a lot to say.

Next Month—Part II: Clark Speaks

Clark: Part II (August, 1991)

©1991, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (1991, August). Clark: A Reminiscence, Part II. Newsletter of the Commodore Users Group of Atlanta, V. 9, No. 8, p. 2.

Clark: A Reminiscence—Part II

By Dallas Denny

My Favorite Things

I like cars, trucks

and trains

I like bacon, ham

and sausage

I like strawberries, blackberries

and apple pie

I like country music, pop

bluegrass

And I like gospel

but I don’t like rock n roll

It is too loud.

I like the Lawrence Welk Show

and the Boston Pop

My favorite color is

red white and blue

I like the flag

of the USA.

—written by Clark, using a Commodore computer and a foot-operated switch.

Last month, I explained how I came to write a computer program called Six Bits for a physically handicapped man named Clark. Next month, I will tell how Clark came to appear before the national meetings of the Civitans Clubs of America and the Association for Retarded Citizens to give an invocation and a speech, using his computer-generated voice.

Clark had been using an electronic device called a Trace II, which used Morse input to scroll LED letters across a screen. The device was no longer being produced, and it broke regularly. Each time it quit, John Dolan, one of Clark’s technicians, had managed to locate the man who had designed it, but only because they had a mutual interest in ham radio. The Trace II had served honorably, but it was time to retire it.

The VIC-20, with its large characters, was a good choice for Clark, for his eyesight was not so good. Even so, he could not use the computer right away. He had to be trained, and we had to provide him with a switch he could use without tiring. Joyce Moore and Wendy McAmis, working together, experimented, finally deciding that foot operation was best. They had the carpenter ship build a special switch which would remain stable on the floor when Clark used it.

Clark caught on fairly readily to the operation of Six Bits, but then another problem became apparent. Although he had heard sentences all his life, he had no experience in making them. Joyce began teaching him sentence construction and grammar.

Clark was soon using his computer every day, and what he had to say was amazing. He was quick to praise, but he was also quick to point out problems. The Cottage Manager, the Team Leader, and even the Superintendent soon began to receive his short but to-the-point communiques. And biographical information began to emerge.

Joyce and Wendy compiled this information into a biography; Clark had written his first book!

I was born normal (I was normal) until I was eight years old and then had a long sick spell. My dad and mom was worried sick. They had an old time doctor. Dad had to go catch a train to get the doctor.

Next Month—Part III: Clark Makes the Big Time

Clark, Part III (September, 1991)

©1991, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (1991, September). Clark: A Reminiscence, Part III. Newsletter of Commodore Users Group of Atlanta, V. 9, No. 9, p. 2.

Clark: A Reminiscence—Part III

By Dallas Denny

Clark worked away at his VIC-20, using it to communicate in his everyday life. It took him laborious minutes to make it say even the simplest things. Wendy McAmis and Joyce Moore and I dreamed about upgrading Clark’s system, but where would we find the money?

In 1984, I moved to Nashville to go to graduate school. One day I told Dr. Floyd Dennis, my advisor, about Clark and our wish to get him a Commodore 64 with a disk drive and a color monitor. Floyd had an idea, and set up a lunch meeting with Roger Blue, the director of the Association for Retarded Citizens of Tennessee. Over moo goo gui pan, we made our pitch to Roger: could the ARC-T help us find a computer for Clark? The deck was stacked, for I had been doing a lot of favors for the ARC-T: setting up a database system to allow them to track the registrants for the upcoming national conference of the ARC, which was to be held at the beautiful Opryland Hotel, as well as appearing as an expert witness in various court cases and due process hearings. Soon, we had a $500 check from the ARC.

Back in East Tennessee for the summer, I took the ARC’s check to Marjorie Nell Cardwell, then the superintendent of Greene Valley, Clark’s home. I shamelessly asked her for matching funds. She met with the Parents’ Advisory Council, returning with a check for a bit more than $200.

Clark’s fund bought hin a C-64 computer, a Commodore 1541 disk drive, a Commodore 1702 color monitor, and his own Votrax speech synthesizer (he had been using mine). We even found a plug-in cartridge that would make the C-64 autoboot. But there wasn’t enough money for a printer. However, luck was with us. Joyce Moore, Clark’s speech therapist, told his story at a meeting of a local computer club, and a 1525 printer was donated. Clark was in business!

Joyce began training Clark in the use of a new program I had written. The program had more than 700 built-in words and phrases. Clark used some of them, ut his failing eyesight kept him from using the full potential of the program. Still, he was “talking,” and it was no longer necessary for Wendy McAmis, Clark’s program coordinator, to manually load his program every morning (something she had been driving to his cottage on Saturday and Sunday mornings for several years to do).

Payback, they say, is hell, but not in this case. Back at Vanderbilt in Nashville, I got a call out of the blue—from Roger Blue. It seemed the ARC-T had been asked by ARC National to provide a disabled person to give the invocation at the ARC national meeting. Would it be possible for Clark to come and speak with the aid of his computer?

Indeed it would. With Marjorie Nell’s approval, Wendy and I and a male attendant loaded Clark into a van with a life and headed for Music City. There, on the stage in front of delegates from all over the country, he gave the invocation he had been preparing for weeks. I had rigged the computer to begin speaking automatically when Clark pressed his foot switch. We were given the high sign, I signalled Clark, he reached for the switch with a trembling foot, and the amplified voice of Sam, the Software Automatic Mouth (we had left the Votrax behind) boomed across the ballroom.

There wasn’t a dry eye in the place, including mine, and Wendy’s, and Clark’s.

Again with Wendy and myself along, Clark repeated his performance, at the request of Al Abeson, ARC’s Executive Director, in front of the national meeting of the Civitan Clubs of America—this time delivering a speech instead of a prayer. That night we stayed at the Opryland Hotel. The next morning, Clark spent two hours on the balcony which overlooked the hotel’s wonderful conservatory, just drinking it all in.

Clark’s two trips to Nashville were the high spot of his life—and mine. Wendy and I were lucky to be able to share in his triumphs. And when Clark’s artificial voice was booming across that ballroom, I looked at Clark and thanked God and Commodore founder Jack Tramiel and the ARC-T for the miracle of his C-64.