Beginning Year Number Nine in Chronic 1A (1987)

©1987, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (1987, Summer). Beginning year number nine in Chronic 1A. Illustrated by John Callahan. Mockingbird (East Tennessee State University), 1981, pp. 8, 10-12. Reprinted in Whole Earth Review, No. 55, pp. 112-114.

Beginning Year Nine won Mockingbird’s First Place Award for Short Fiction.

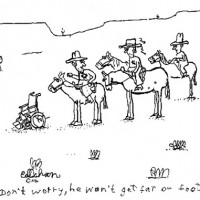

This is the first of four short stories about a man with quadriplegia who has been housed in a mental institution for no legitimate reason. Three of the four, included this one, have been published and received honors. Its appearance in Whole Earth Review was illustrated by disabled cartoonist John Callahan.

Whole Earth Review Pages (PDF)

About This Story

Throughout my lifetime I have worked in a professional capacity with adults with developmental disabilities– first as a developmental technician, while I was in college, and later as a psychometrist and applied behavior analyst. Periodical psychological testing of my clients was required (not so much now, at least in Georgia), but routine. My work as a behaviorist, on the other hand, was endlessly fascinating. Finding out why client were behavior in a certain way was rather like detective work, especially since many were nonverbal. I soon discovered the misbehaviors (I’m tempted to put the word in quotes) about which I was consulted were logical responses to their environments, both inner and outer. What made them tick also made me tick. We were the same.

My respect and sympathy for my clients was reflected in my short stories, many of which touched upon disabilities of one sort or another. This vignette is related to three others. Three were published to acclaim of one sort or another. One won first prize for fiction in Mockingbird, the literary and art journal of East Tennessee State University. Two others were selected by the journal Kaleidoscope: International Magazine of Literature, Fine Arts, and Disability for reprint in celbratory anniversary celebrations. One appeared in Carol Donley and Sheryl Buckley’s edited text The Tyranny of the Normal. I was flattered beyond belief to find my work appearing in an anthology alongside such literary giants as Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke, Ray Bradbury, Donald Barthelme, Edgar Allan Poe, Toni Morrison, John Updike, Alice Walker, Flannery O’Connor, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Eudora Welty, Anne Beattie, and Victor Hugo!

The fourth vignette of this series of four has never been published. If you select Short Fiction from the drop-down menus at the top of the screen on the home page, you’ll find it.

About John Callahan

I absolutely loved John Callahan’s illustrations for my story. I wrote him a thank you letter, which I sent to him via my editor at Whole Earth Review, and I made a point of buying his autobiography Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot!

I absolutely loved John Callahan’s illustrations for my story. I wrote him a thank you letter, which I sent to him via my editor at Whole Earth Review, and I made a point of buying his autobiography Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot!

Callahan was over-the-top, made bitter and militant (but rather charmingly so) by his quadriplegia, which was as the result of a drunken auto accident when he was 21. He was unapologetic about his often politically incorrect cartoons, and I admired him for that. He died in 2010, at age 59. Click the button below to see New Mobility magazine’s excellent obituary.

I saluted Callahan as one of my favorite cartoonists in my Second Life blog. The others on my list were Charles Addams, Gahan Wilson, Charles Rodrigues, and Shel Silverstein. Coincidentally, I wrote my post about Callahan mere months after his passing; in fact, I learned about his death when I Googled him while writing.

Beginning Year Nine in Chronic 1A (Text)

©1987, 2013 by Dallas Denny

Source: Dallas Denny. (1987, Summer). Beginning year number nine in Chronic 1A. Illustrated by John Callahan. Mockingbird (East Tennessee State University), 1981, pp. 8, 10-12. Reprinted in Whole Earth Review, No. 55, pp. 112-114.

Beginning Year Nine won Mockingbird’s First Place Award for Short Fiction.

Beginning Year Nine in Chronic 1A

Every thirty seconds Johnson takes a deep breath. Then he does these things: tugs at his left earlobe; touches his thumbs and forefingers together, making a triangle which he holds high in front of his face; puffs out his cheeks, expelling the air which he has been holding in with a rush and a flourish. Johnson has been doing these things with psychotic compulsive regularity all morning, about four hours now since breakfast. It makes me sad to watch him. When first he came here, before the Thorazine, Johnson understood the causal relationships between his body movements and certain processes of the universe. He was wonderful to watch, running the cosmos, orchestrating the movements of planets around stars in galaxies near the event horizon, as well as taking care of business closer to home—choreographing the traffic lights of Cleveland, Ohio, for instance, or regulating the reproductive cycles of certain species of cyclid fish In the Caribbean— all these things with precise swirls and dips of his wrists.

One night, in the therapeutic semi-darkness of the bedroom, while the attendant dozed in the nursing station, Johnson, thinking I was asleep, explained it all to Parsons, who was choking to death and therefore unlikely to betray the confidence: how it was an intricate and subtle business, oiling the machinery of creation, how every slight action had to be carefully judged lest it produce intergalactic catastrophe, how it was once necessary to interfere slightly with the rumination of a particular Hereford in Colorado so that a particular diner in a particular restaurant would ingest a particular quantity of a particular enzyme in his steak on a certain preordained night, which would affect a minor but crucial decision he would make the next day at his Wall Street brokerage house. How this decision would effect the New York Stock Exchange, slightly at first, but then snowballing, reducing the value of the stock of a troublesome company in Georgia which poured too much effluvia into the atmosphere and into streams. How the decline in stock prices would anger stockholders and lead to changes in composition of the board of directors of the company— changes which would send a certain stockholder home in quiet fury to take it out on his wife and son, who would flee to the wife’s mother’s house. Consequently, the boy would walk an unaccustomed route to school the next day, and would therefore miss kicking a rock— a rock which, Johnson assured Parsons, who was by now quite blue, contained the spirit of Booker T. Washington and would be better left undisturbed, lest it turn in wrath and wreak peanut havoc upon the land.

Critical work, this, and now Johnson, thanks to the bitter brown pill, in no shape to perform it— Johnson, since the little doctor strode through the ward one day and with several almost illegible strokes in Johnson’s chart, robbed him of his marvelous complexity of behaviors, reduced to only three: safety off, aim, fire.

It’s not much of a system. The safety, which is of course disguised as an earlobe, must be clicked off before every shot. The fingers are used to sight in the target. And when Johnson exhales, puffing out his cheeks, he fires, always at a moving target. Johnson is a sportsman. He doesn’t shoot at sitting ducks. But he also doesn’t exhale until he fires. As time goes by and his face grows more red, he will settle for less and less of a movement, even a twitch. But sometimes, when nobody is moving, Johnson will jump from his chair, dash across the dayroom, and make somebody move, more often than not sending them sprawling to the floor. Then he exhales with a whoosh and returns to his seat.

Everybody is onto Johnson’s game, except of course the aides— they’re called technicians now, but that doesn’t make them any smarter or more perceptive. Sometimes when Johnson aims, everybody in the room will freeze, hanging in space like so many icicles, causing Johnson untold consternation, driving him in desperation to fire on the technicians. Johnson hates to shoot the technicians.

Johnson will keep up his shooting until six o’clock this evening. Then his relief, a quasi-mammalian tentacled sea-dweller from Aldebaran IV, will take over. Johnson sometimes wolfs his breakfast because the Aldebaranan dislikes being relieved late. Once it sulked, refusing to take over in the evening, which resulted in poor Johnson having to carry on for thirty-six straight hours. It was quite a night, with technicians about bearing syringes, yelling at Johnson to go to sleep, and he fighting to stay awake through a Dalmane and Librium fog. The Aldebaranan replaced a much more reasonable plantlike sentient from a planet in the Andromeda galaxy after Johnson’s mental processes were vasectomized and he was assigned his present, repetitious duties.

Today Johnson is blasting Morgan, the new guy. He isn’t aiming directly at Morgan, but everybody knows Johnson’s projectiles aren’t subject to laws of normal Einsteinian space-time. Every time Johnson shoots, Morgan leaps up and finds another chair. Morgan has been from chair to chair all morning, and this hasn’t escaped the notice of the head technician, although she has no idea why he has been so restless. Morgan doesn’t know it, but he’s working toward receiving an intramuscular present— one formulated to immobilize him as effectively as ropes by stripping him of all desire for movement, even if Johnson had a real gun and not a breath gun.

I’m a Johnson-watcher by orientation rather than by inclination. My wheelchair is turned facing him, and the only one else in my line of sight besides, about half the time, Morgan, is Hewlitt. Hewlitt sits in one spot all day, unless told to move. It’s as if he had a perpetual overdose of what Morgan is about to get. Nobody on the ward knows just where Hewlitt has gone, forsaking his body, but we all hope that one day soon his spirit will reappear, hover like a hummingbird for a moment, and then descend, reanimating Hewlitt and telling us all about its mysterious journey.

I used to want to ask Johnson how to control things, how to control even my arms and legs, but he would have only laughed. Johnson is convinced I’ve gone the same place as Hewlitt, that we have both surpassed the need for our bodies, that if he is dedicated enough he might someday be like us. Besides, he would have said, had I been able to ask, how was he to know I wasn’t a spy, sitting immobile in my wheelchair for eight years in order to trick him into revealing his methods? Johnson thinks like that. Now his methods are lost, perhaps irretrievably, unless the Thorazine mines all play out.

Margaret has come in now. Margaret is homely, but is provocative and suggestive nonetheless, since she is convinced that she is beautiful. Today her hair is frazzled from too much teasing and she is wearing a pair of green shorts over pantyhose with a leg-length run in them, and ugly flat used-to-be-white hospital slippers. But I want her and she knows it, and she will probably manage to brush against me in a tantalizing way: she delights in my inability to initiate anything. But she isn’t stingy with herself. Once she brought me blessed relief in the linen room and then traipsed out, leaving me with my pants around my knees and unable to cover up my embarrassment. I was panic-stricken, knowing I would eventually be discovered by a technician. But Hewlitt, surprisingly enough, had come in and wheeled me to the bathroom, where my partial nudity wasn’t conspicuously suggestive of sexual encounter, but was, rather, rewarded, since staff thought I was attempting to toilet myself. Hewlitt operates entirely at a spinal-motor level. I later found out that it was Daisy, to whom Margaret often brags of her exploits, who had told Hewlitt to rescue me.

Daisy is the perpetual virgin, a Polyanna with a kind word or deed for everybody, but who about two or three times a year has a seizure that cuts out her cognitive mechanism and leaves her with the psyche of a remote aboriginal ancestor who has a taste for human flesh and a distrust of closed areas. At these times Daisy’s body, driven by the spirit of Amanaga Io Managa, becomes so violent that even Jenkins, the three hundred pound technician, is afraid of her. Daisy will be here for a long, long time, I’m afraid, because in their efforts to banish Managa from Daisy’s brain the doctors sent currents through her head, Reddy Kilowatt on safari. But the electricity, not finding she it was sent to exterminate, turned instead on the native fauna, marching through Daisy’s brain like Sherman marched through Georgia. And neurons, unlike trees, do not send shoots up from their blackened stumps. Daisy cannot remember names or faces from day to day: persistent will be the suitor who can come to know her well enough to enjoy her favors. Daisy is a proper type of girl. But the aborigine, with wits and memory intact, still surfaces from time to time, hating and hurting, using the primitive weapons of tooth and toenail to bite and kick her way towards freedom.

Margaret, on the other hand, has muscles that periodically betray her, locking her in mid-stride into rigid catatonia, forcing her to stand like a bargain store manikin for an hour or two before she begins to melt to the floor, wilting like a candle in the hot sun.

Johnson began shooting Margaret as soon as she entered the day room, but she is deflecting the bullets with her hand, causing them to arc gracefully right to Morgan, who is still getting hit, still switching chairs, still speeding obliviously towards IM oblivion. I would signal Margaret to come turn the cassette over, since it has long since reached the end, but it is too close to lunchtime, and it wouldn’t be finished before they come to get me for my tray of pureed pap. I listen to two or three tapes a day, when I can get them. They belong to Dr. Sellers, the psychologist, who Is blind. Often the tapes are of articles from professional journals, but sometimes there will be a talking book, Mark Twain, perhaps, and once the Marquis de Sade’s Justine. Today the tape is entitled “Endocrine status of 17 institutionalized chronic schizophrenic individuals: Evidence of irregularity.” Yesterday there was an article from a psychotherapy journal about James Joyce. A lot of the stuff on Dr. Sellers’ tapes went over my head at first, but finally I learned what all the buzz words meant.

When I first came here about a year after the Accident, everybody figured the kid had checked out, that there was no longer a driver for the car. It was Dr. Sellers who had insisted that a thorough evaluation of my intellectual functioning be done. She had excused herself on the grounds that since I couldn’t talk much and she couldn’t see me move, Dr. Starks should test me. Starks had tested me, angry because he had to test a patient who wasn’t from his unit. He had pinched me viciously on the legs. He should have known I couldn’t feel it. And he had lied, reporting that I couldn’t comprehend any of the test items and that I was incapable of rational thought. And when Starks was through with me and a technician had wheeled me back to the ward, Dr. Sellers had on hand an electric typewriter with a special mechanism on it which allowed me to poke a pencil into holes to strike the keys, and had waited patiently as I with my spastic but movable right arm had typed a document damning Starks. I’m not sure to this day how she knew I would able to type that letter, or how she knew Starks would abuse me, but my letter, submitted with snapshots of my legs, which had felt nothing but had bruised beautifully, had been sufficient to cause Starks to lose his position and his professional license.

After that everybody was supposed to know that my brain is normal, but a lot of people don’t believe it, or else forget. People talk to me a lot of times in baby talk, or worse yet, don’t talk to me at all. I overhear a lot of things I shouldn’t because people forget.

I used to get angry, overcome with loneliness and frustration, and showed it by non-compliance, by soiling and wetting myself, by refusing to feed myself, by howling and banging my arm on the arm of my wheelchair— but Dr. Sellers came by one day and quietly told me that if I continued I would be moved to Chronic III A. That’s the unit where all the real space cadets live.

The residents of Chronic III A have had their brains replaced by electrical gadgets. Their limbs move stiffly and mechanically just like the creatures in the old movie The Night of the Living Dead. The electric devices aren’t solid-state electronics LEDs, microprocessors, circuit boards. No, they are Civil War surplus: Leyden jars, static electricity generators, Crookes radiometers, obsolete and faulty, making the air of Chronic III A smell of ozone and machine oil and bristle with static electricity. Worn relays click with every bend of every elbow, and even the lights in the eyes of the patients spark and sputter because of loose connections. A transfer to Chronic III A is a one-way warp to electro-mechanico-robotic existence. Bad karma. I do less howling and banging of my arm on my wheelchair now.

I’m getting hit by a few Johnson-bullets now. Johnson won’t shoot them until tomorrow, but he’ll project them backwards in time until today. They don’t really hurt; they’re just annoying. Margaret, can you read my thoughts? Don’t pretend you can’t. Linen room, Margaret. Linen room. LINEN ROOM. L—I—N—E—N

R—O—O—M. Yes. Yes, Margaret. Yes. Yes.

Yesyesyesyesyesyesyesyesyesyes.