Preserving Trans History: A Short History and Suggestions for the Future (2014)

©2014 by Dallas Denny

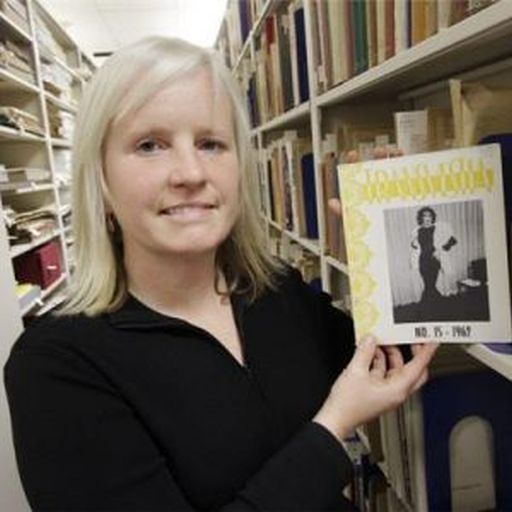

Thumbnail Photo: Lara Wilson, Director of Special Collections and University Archivist, University of Victoria

Source: Denny, Dallas. (2014). Preserving trans history: A short history and suggestions for the future. Keynote at Moving Trans* History Forward, University of Victoria, B.C., 21-23 March, 2014.

Conversion of my slideshow from Open Office to PowerPoint format reordered some of my slides and blanked a couple. That explains why the talk doesn’t follow the slides correctly all the way through.

Listen to Audio Recording (80 kbps MP3)

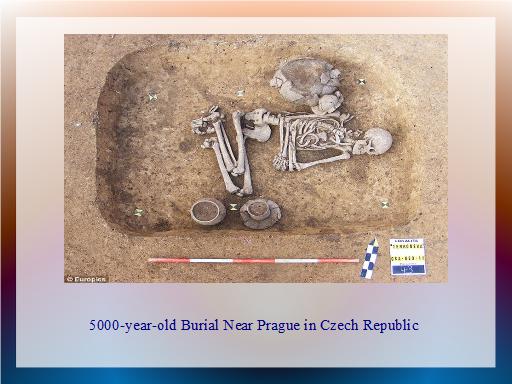

Gender variance has a rich and ancient history—one we have only recently begun to rediscover. Evidence of this history ranges from Paleolithic burials, which surface with some regularity…

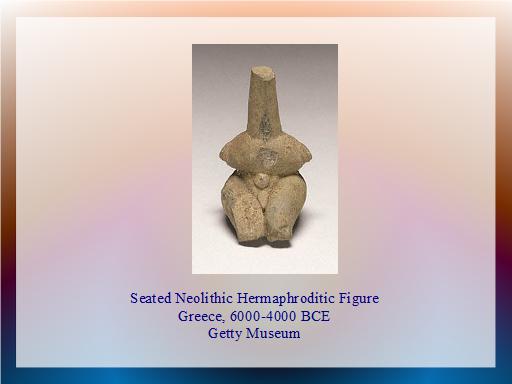

…to ancient works of art… In his book The Prehistory of Sex, anthropologist Timothy Taylor writes that curators of Victorian-era museums found hermaphroditic figures troublesome and often hid them away from view (or destroyed them)….

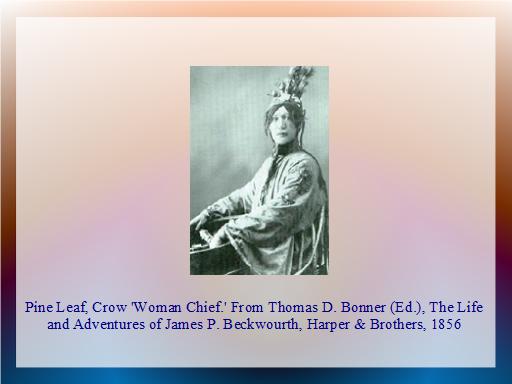

…to tribal societies with established trans and nonbinary roles. Will Roscoe has documented several hundred such among North American Plains tribes…

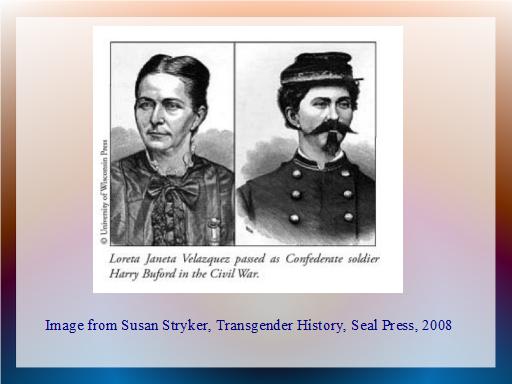

…to historic personages…

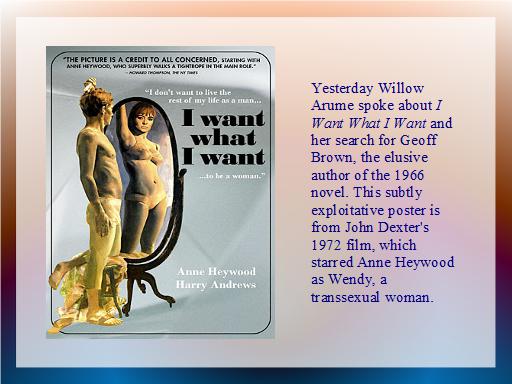

And of course we have been documented (often in negative ways) in fiction and on film. I say the poster is subtle because my eyes focused on the woman in the mirror and it took me a moment to realize the figure outside the mirror wasn’t that of a woman. If you attended Willow Arune’s talk yesterday, you saw the real item. It’s now part of the transgender archive here at the University of Victoria.

We of course have no way of knowing how gender-variant people who lived before the twentieth century identified then or would, had they the chance, identify now. As Susan Stryker pointed out in her keynote last night, it would be a presumption to call them trans—but we do know in many cases how people lived and died.

Until recently this rich history was ignored and overlooked by almost everyone—even many trans people considered our history unimportant or irrelevant.

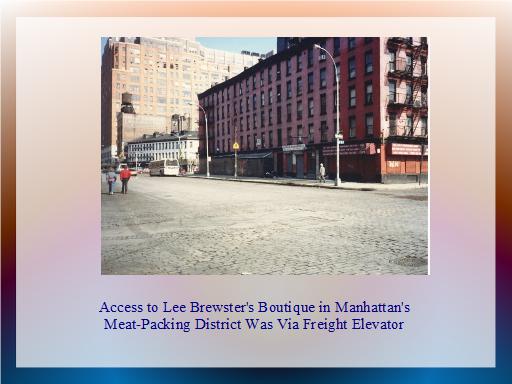

Here are a couple of examples. Lee Brewster was a potent force in early trans organizing. I’ll use male pronouns to talk about Lee, because that seems to have been his preference.

Several years before his death, I visited Lee at his trans boutique in Manhattan’s and asked him to please make provisions for the preservation of his personal historical materials. I hope he did, but I suspect he didn’t.

Lee’s boutique was in Manhattan’s meat-packing district, and access was via a freight elevator. There was no indication from the street that a boutique for crossdressers was just above. While I was interviewing Lee, men in business suits would sneak in and go to the back of the store to examine panties and bras and false eyelashes, make their purchases with their eyes cast down, and leave, all without a word.

In the National Transgender Library & Archive collection there are two pairs of Virginia Prince’s shoes, dating from the 1960s (she had small feet). When transgender activist Alison Laing showed me a pair of shoes she was wearing when she was chased by a Philadelphia policeman in the 1950s, just because he realized she was crossdressed, I begged her for those shoes. I even offered to buy them from her. She was unable to convince herself I was serious, and eventually sold them in a yard sale.

When attention WAS paid to trans historical materials by non-trans scholars, they were subject to misclassification, misinterpretation, or active repression. Often, we were misclassified as gay and lesbian. Yesterday Ardel Thomas talked about early musician Gladys Bentley and Vernon Lee. Another example is Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, which has long been classified as a lesbian novel, despite the fact that Hall’s protagonist wears men’s clothes and calls himself Stephen.

How Things Were in the Mid-XXth Century

Since the time of my birth in 1949, the world has changed in amazing ways. Here’s now things were in the mid-Twentieth Century.

Small groups of crossdressers were meeting in California and the North Atlantic States and corresponding.

Transsexuals (a few of us, anyway) were finding our way to Harry Benjamin and other sympathetic doctors or to gender clinics. The clinics discouraged interactions between patients. Unless they happened to live in places like New York and San Francisco, where there was rudimentary community, transsexuals were on their own. I love this photograph by Barry Kay because for me it typifies our isolation.

For both crossdressers and transsexuals, guilt and shame were strong emotions. Purging was common. Clothing, cosmetics, books, videos, and correspondence would be burned or discarded. I’ve known transpeople who told me they purged dozens of times. God knows how much historical material was destroyed!

Outside of a few specialty stores like Lee Brewster’s boutique, trans materials were hard to come by.

And what trans materials were there?

A treatment-oriented and often pejorative psychological and medical literature found in university medical libraries…

…exploitative magazines like Female Mimics for the curious and the intrigued…

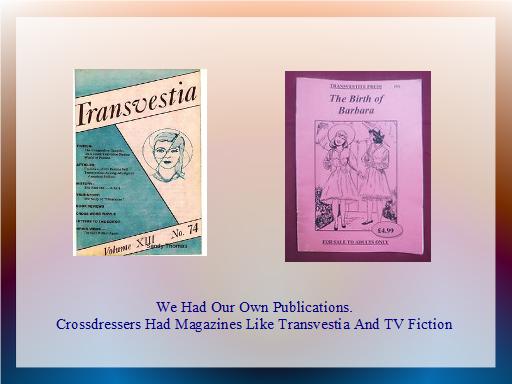

… and crossdressing literature, which consisted of magazines filled with personal stories and erotica, and digest-sized wish-fulfillment fiction books.

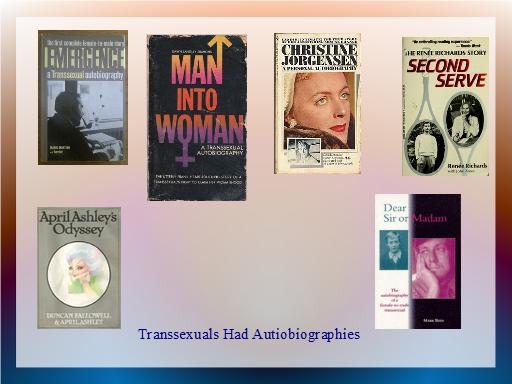

In mainstream publishing, popular literature about transsexualism consisted primarily of autobiographies. That’s because we were locked out of the academy. Autobiographies were the only books transsexuals could get published.

Anthropologist Anne Bolin, who is cisgender, told me she once had a journal article rejected by peer reviewers. On the front page, a reviewer had written—“obviously a transsexual.” The subtext? What could a transsexual possibly have to say worthwhile about transsexualism? And of course, “No transsexual is MY peer!”

In the mid-1980s the two arms of the trans community—crossdressers and transsexuals—came together, and things began to change. We began to define ourselves, and to develop new terminology to describe ourselves and new ways of looking at ourselves. Out of this was born the contemporary trans movement with its emphasis on diversity and questioning of gender roles in the larger society. In his talk here yesterday, Michael Waldman listed just a few of today’s many gender-variant and trans identities.

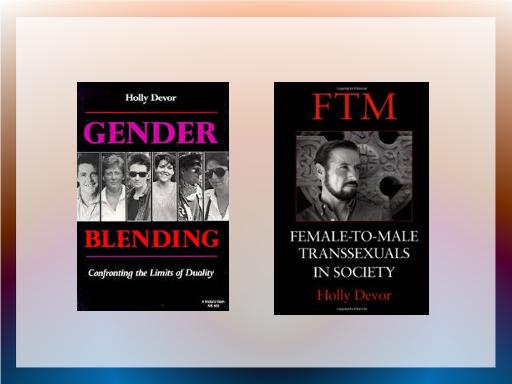

Part of this new discussion was an article by Holly Boswell entitled “The Transgender Alternative.”

Before 1992 or so, when we came into the movement we were expected to declare ourselves crossdressers, transsexuals, or drag queens. Those were the three available options and we pressured each other to conform to them. Anthropologist Anne Bolin brilliantly documented this in her 1988 book In Search of Eve.

In early 1992 Holly’s article appeared simultaneously in the journals TV-TS Tapestry and Chrysalis Quarterly. I was founder and editor of Chrysalis and would later be editor of Tapestry. There, I reprinted Holly’s article.

The impact of Holly’d The Transgender Alternative was immediate and dramatic. By 1994 the term transgender had become the consensual umbrella term for all of us. That doesn’t mean everyone liked it. Essentialist transsexuals in particular felt they had little in common with crossdressers and transgenderists. Even so, when Anne Bolin revisited the community in 1993 she found what she called—I love this term!—a splendor of gender. There was every sort of identify imaginable, and every one of them was proper and okay.

I was lucky to be present at this historic and formative time. I will now jump track a little and discuss my personal history.

1963

In June, 1963 my family moved to Murfreesboro, a town in Middle Tennessee with a population of 30,000. I was 13 years old. I rode my bike in sweltering heat to the Linebaugh Public Library, where I looked through the card catalog (remember those?), using every term I knew, hoping to find information about what was going on with me.

I found two books. I don’t remember the authors or names, but I certainly remember one was in the Reserve section; the second was in the stacks.

I wasn’t about to ask the librarian for the book on reserve. She would have refused to give it to me or perhaps called my parents, and I couldn’t risk that. So I looked for the other book, which was, according to the card catalog, on the shelves. It wasn’t there.

I went back every week or two during that hot summer, looking for that book, but it was never on the shelves. I continued to search, even after I graduated from high school. I now realize it was no doubt stolen by someone very much like me or destroyed by someone who thought people like me should be dead.

1972

In the bookstore at Middle Tennessee State University’s bookstore I chanced across a compilation of underground comix that contained something remarkable. There was a story (I don’t recall the author or the title or the comix in which it first appeared) about a young transwoman in San Francisco who realized she had run out of hormones. I read as she went outside and grabbed onto a passing cable car as she went out to search for her drugs, and then I had to stop. It was the first depiction of transsexualism I had encountered that was in any way positive, and it was just too much too take. I returned often to the bookstore but just couldn’t make it past the frame in which she jumped on a streetcar and rode away in her search for hormones. I never finished the piece.

When I finally found the money and went back to the bookstore to buy the book, it was, alas, gone. I’ve never been able to source that book. I would love to finish it.

1974

In 1974 I was a master’s student at the University of Tennessee.

My first assignment as a grad assistant was in the lab of Dr. Joel Lubar, who was studying biofeedback as a way to reduce seizures in people with epilepsy.

This was a year or so before 8-bit microchips became publicly available, so the lab had rack upon rack of 4-bit electronic components, all built by a mysterious graduate student named Kad. The other lab assistants assured me something was up with Kat, but refused to tell me what.

I didn’t realize it, but Kad was transitioning. Shortly after I began my program she requested that she be called Rhianna. Everyone, unsurprisingly, flipped out. But Rhianna was the only one who could keep the lab, with its large NIMH grant, running, so her graduation was assured.

When I finally met Rhianna, I attempted to disclose by clumsily suggesting we go to a drag show. She promptly informed me drag was exploitative toward women. And so I didn’t tell her about myself.

I’ll talk a bit more about Rhianna in a moment.

Late 1970s

In the mid-970s I was out of grad school and had entered the workplace. Renée Richards, Jan Morris, and Canary Conn, all of whom had had sex reassignment, had written (what else?) autobiographies, and were appearing on television talk shows.

Canary in particular caught my attention when I saw her on the Dick Cavett Show. She was pretty and passable and entirely comfortable in what was a new role for her. Wow! I thought. Could I pull that off?

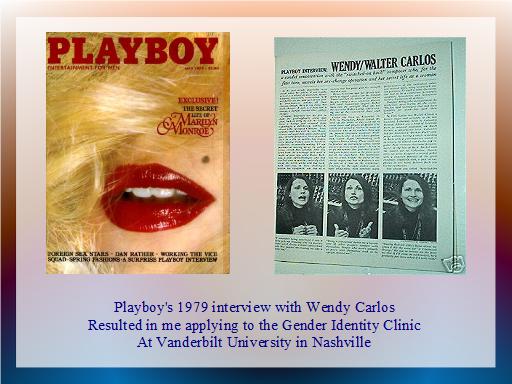

May 1979, Playboy magazine published an interview with Wendy Carlos. She put hormones on my radar. Somehow I had never just thought of them until then.

In 1979, I applied to the Gender Identity Clinic at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. I paid $500 and took a battery of psychological tests I had been trained to administer. When it was time for the results of my admission procedures, Dr. Embree McKee told me I wouldn’t be accepted into the program. And why? Because I was working in a professional capacity, because I had two college degrees, and because I had been married to a woman. I could function in the male role. “Real” transxexuals couldn’t because they had a mental illness. They had personality and character disorders and other co-existing psychiatric disorders, and were shrill and manipulative and unreliable.

I was turned down because I wasn’t dysfunctional enough to be transsexual. In other words, I just wasn’t screwed up enough.

Until then I had been apolitical, at least about gender. This was the experience that politicized me.

I talked about the experience last November in a keynote at the University of Missouri at Columbia.

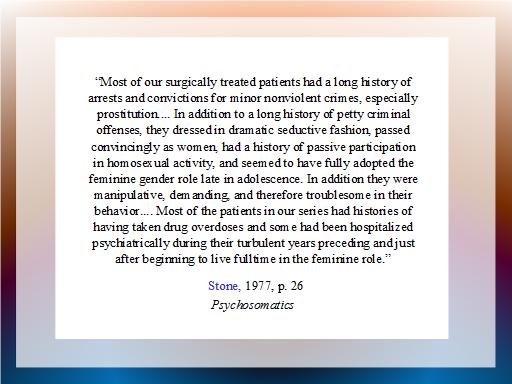

Immediately after the rejection I took myself to the medical library at Vanderbilt and spent months reading everything I could dig up about transsexualism. There I found an objectifying and abusive medical literature that told me Dr. McKee was right: transsexuals were screwed up people indeed.

I used this quote in 1998 in a presentation at the HBIGDA symposium in Vancouver, mere miles from Victoria, where I am speaking today:

Here’s that talk as presented at Fantasia Fair in 2004:

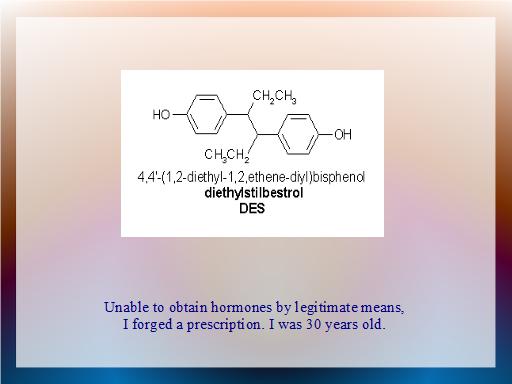

And so, around the time of my 30th birthday, I forged a prescription for hormones. I didn’t do it lightly, and later I worked hard so no one else would have to do it, but I have no regrets.

After a great deal of research, I placed myself on the potent estrogen diethylstilbestrol. Today we know what a dangerous drug DES is. In 1979, no one knew. When the news broke about DES I consulted with my physician (me) and switched myself to Premarin.

That same year (still 1979, for those who are counting) I saw the crossdressing group Tri-Ess on television.

Tri-Ess, known more formally as The Society for the Second Self, has a focus on heterosexual crossdressers, which is fine by me—but they had and continue to have an exclusionary no gays, no transsexual membership criterion with which I take issue.

I wrote, telling them I knew I was ineligible for membership, but asking to please be put in touch with someone who knew about transsexualism.

They gave me the address in the upper left corner. Some of you may recognize it. It belonged to Virginia Prince, the founder of Tri-Ess. Virginia was not herself transsexual and was known for doing everything she could to discourage those who were.

I poured my heart out to her in a letter and got a reply that scared the hell out of me.

Virginia told me I had better get used to deceiving others, for the act of passing as a woman was a form of deceptive. She talked a lot about sex and gender, but at that time I (and most other people) didn’t understand the difference.

And so it would be ten more years before I would find community. That’s right—Tri-Ess’ exclusionary membership policy set me back ten years.

That wouldn’t have been the case if I had anywhere else to turn—but I didn’t.

My letter, and Virginia’s reply, are in the National Transgender Library & Archives in the Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan.

1984

In those ten years little happened other than my body continuing to feminize with estrogens. In 1984 I came across Pat Morgan’s The Man-Maid Doll in a used book sale in a mall in Johnson City, TN. It was the story of a trans prostitute. Patricia was very much like the transsexuals I had read about in the library at Vanderbilt. She typified the word dysfunction. Her story was a good read, but useless to me.

1985

The next year, at the national conference of the Animal Behavior Society at Duke University, I came across Susanne Kessler & Wendy McKenna’s Gender: An Ethnomethodological Approach. It was first published in 1978 by John Wiley & Sons. One of the vendors at the conference, The University of Chicago Press, had just reissued it as a paperback.

Kessler and McKenna’s book was a landmark work, in which they undertook a deconstruction of gender. In an appendix I found a case study of a transsexual woman named “Rachel.” Her identity and circumstances were heavily disguised, but I recognized Rhianna from the University of Tennessee.

Later, I would write a chapter about this for the journal Feminism & Psychology.

Still, though, I was isolated. I knew no other transsexuals and found no other literature.

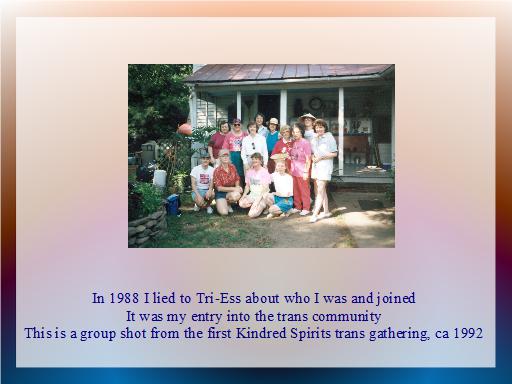

In 1998 I lied about who I was and joined Tri-Ess. My hope was doing so would lead me to other transsexuals. I knew there were other people like me, and it stood to reason that Tri-Ess would have knowledge of them.

1989

I indeed found trans community through Tri-Ess. In 1999, at a meeting in Charlotte NC, I met Asheville’s Jessica Britton, who told me about her friend Holly Boswell. I arranged a meeting with Jessica and Holly and one of them showed me an issue of IFGE’s TV-TS Tapestry, which featured state-by-state listings of support groups and helping professionals.

For those who might not know, Kindred Spirits was a retreat held at Sunnybank Inn in Hot Springs, NC, in the Appalachian Mountains. Holly Boswell ran the operation for more than two decades, and took on the role of setting up the first, but the decision to hold the first event was made in a hotel room at an IFGE convention in Houston, Texas, immediately after a talk by the late Rena Swifthawk. Present were Holly, Wendy Parker, myself, Alison Laing, Angela Brightfeather, Nancy Nangeroni, and three or four others whose names I am ashamed to say I don’t remember. Virginia Prince had attended the session, where she interrupted Rena’s sweetgrass smudging by speculating about loudly and unwantedly about whether the fire alarm and sprinklers would go off. They didn’t.

The only support group I could find was within driving distance was in Atlanta, some 250 miles from my home in East Tennessee. I phoned more than 50 times before someone picked up the phone. I met with the founders the next month, and the month after that they asked me to run the group for them.

And so, with a modicum of help, I moved to Atlanta in December, 1989. I changed clothing just before I left my house, leaving my jeans and shirt and tennis shoes on the floor like the shell of a chrysalis and drove in a U-Haul truck to Atlanta. There, I was lucky enough to find a professional position doing just what I had done in Tennesseee—applied behavior analysis with a population of adults with developmental disabilities. I worked in that position until I reached retirement age.

Now, throughout all this, the only thing I had been looking for was support—literature, peers, information—to learn more about myself and help me transition gender roles. I had assumed I would do the proper transsexual thing and disappear into the woodwork—but I found I couldn’t walk away from the many people who, like me, were unable to find information. As a helping professional, I just wasn’t able to ignore the many others like me who were in desperate need of information.

This is why I sometimes call myself an accidental activist. It was never my intent. It just happened.

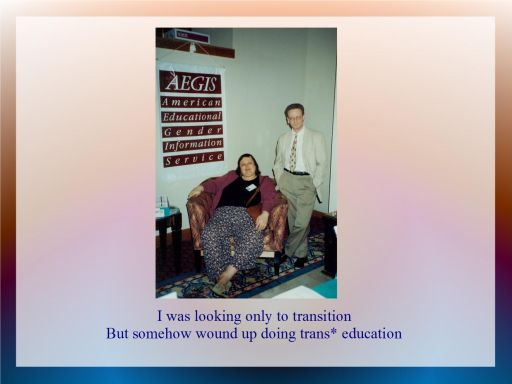

That’s me in 1993 with anthropologist Jason Cromwell. The photo was taken at the Southern Comfort conference. I was one of the originators of that conference.

1990

As 1990 began I immersed myself in the newly discovered gender community (the word transgender had not yet come into popular usage, so that’s what we generally called it.)

That year I launched the nonprofit American Educational Gender Information Service and founded the still existing Atlanta Gender Explorations Support Group.

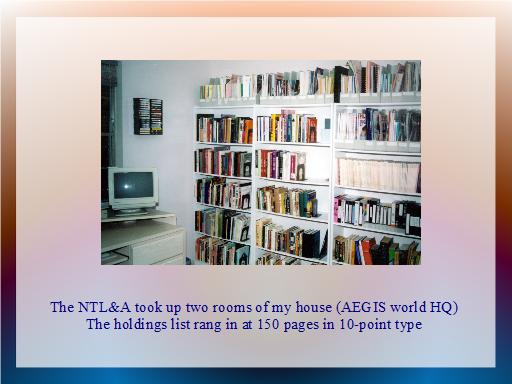

As soon as I had made contact with Tri-Ess I had begun begin acquiring trans material through new contacts with community. Through AEGIS I began a newsletter exchange with more than 100 support groups and other organizations around the world and I picked up books and magazines and pamphlets and flyers at every opportunity.

I remember an early conversation with Ms. Bob Davis, who is in the audience today, in which we speculated about what the materials we were acquiring were worth. I thought we were talking at the time of price, but I now think we were both thinking just as much about the intrinsic historical value of the material we were collecting.

That same year, I started compiling a bibliography of the trans material I owned and the material I knew about. I began by mining the reference sections of the many journal articles I had photocopied years earlier at the Vanderbilt medical library; when I had worked my way through four file drawers of those, I spent a couple of months at Emory University, copying more recent articles. I worked on the bibliography every day, and before long it was of considerable size. I began sending out copies with membership in AEGIS.

1992

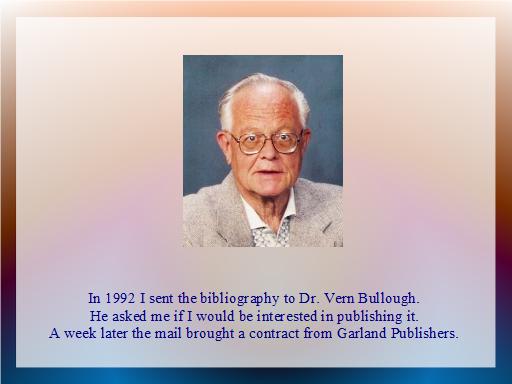

When I sent the late Vern Bullough a copy of my by now huge bibliography, he asked me if I would be interested in publishing it. I said yes, and within a week I received a contract from Garland Publishers.

1994

This is the book that resulted. Viviane Namaste mentioned it in her keynote yesterday.

It’s available only in hardback on acid-free paper that is supposed to last hundreds of years. It weighs in at more than 700 pages, 550 of which consist of thousands of listings of listings of books, magazine and journal articles, newspaper articles, films, and recordings.

It is, so far as I know, the first book-length contribution to the medical and psychological literature of transsexualism BY a transsexual.

1995

By 1993, my private collection took up two good-sized rooms in my rented house.

In 1995 I donated the collection to AEGIS and launched The Transgender Historical Society and the National Transgender Library & Archive.

1996

By 1995 I had become convinced the internet would change just about everything. In particular, I thought it meant the end of transgender community brick-and-mortar nonprofit clearinghouses. By that I meant the days of someone sending a letter of asking for information and receiving, two weeks later, an envelope stuffed with as much information as the nonprofit would afford to send were over. Such a model made little sense when with a modest investment a website could provide practically limitless information instantly to an almost infinite number of people. There were no postage, paper, or printing costs for internet-based organizations, and they didn’t need a physical plant. Most importantly, the internet model didn’t require substantial donations of money.

In 1996 I began a multi-part series in the newsletter AEGIS News in which I took a look at the trans community as it existed then, and in which I speculated about the future.

2000

In 2000, AEGIS rebaselined as Gender Education & Advocacy, Inc, which would have a primarily online presence. GEA has been dormant for years for want of a web designer, but thanks to WordPress, I plan to take on that role myself. I can’t say I’ve brought WP to its knees, but at least we are uneasy friends.

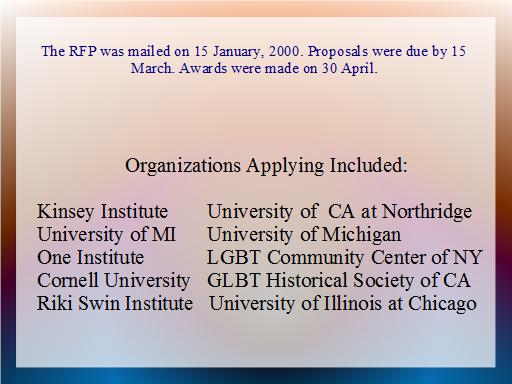

Now, if GEA was to live online, several rooms full of books became a problem. To keep it, we would need to perpetually chase money to rent storage space, something that made little sense in our new incarnation. On January 15 we published a request for proposals from nonprofit institutions interested in receiving the National Transgender Library & Archive.

The response was gratifying. We received responses from, among other places, The Kinsey Institute, the GLBT Historical Society of CA, The One Institute, the GLBT Community Center of New York, The One Institute, the Rikki Swin Institute, and at least five first-rate universities.

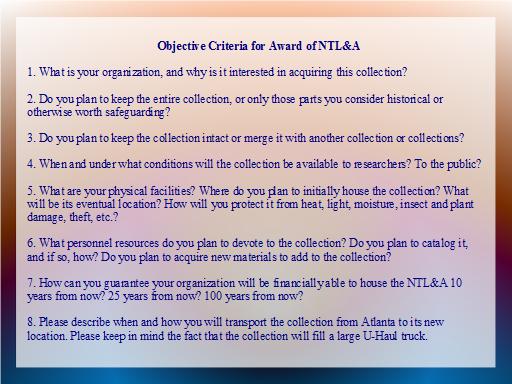

I developed both objective and subjective criteria for evaluation of responses.

On 30 March, after much thought discussion, the GE&A board awarded the collection to the University of Michigan, with any duplicates to go to GLBT Historical Society of CA.

In April or May, Labadie curator Julie Herrada flew to Georgia and the materials traveled by truck to U. MI. The collection absolutely filled the largest-sized U-Haul truck available.

2002

By 2002 all materials were catalogued and online and available to researchers and the general public.

Last night I did a search for the word transgender on the U MI library website and got more than 7000 hits. These were substantive hits, books and journal issues mostly. By way of contrast, when I searched the online database of Emory University in Atlanta in 1991 I found fewer than one dozen entries.

Here’s just one of those seven thousand listings at the University of Michigan. It covers many issues of the Gulf Coast Transgender Community support groups’ newsletter The Flip Side.

As you can see, it’s on page 8 of 400. 400 pages of trans listings! I know every one of those items wasn’t on the truck I sent to Michigan! Clearly the mere establishment of a trans archive in Michigan has resulted in donations in the form of money and materials—and clearly the university itself is proud of the collection and is motivated to grow it. And clearly, the collection has grown since 2000.

Is that going to happen here in Victoria?

It’s already happening. Richard Ekins chose Victoria as the repository for his extensive collection. Stephanie Castle donated her materials. Reed Erickson’s daughter donated material from her father. Yesterday Willow Arune donated the materials she brought for her talk yesterday. And I’m happy to say the transgender conference Fantasia Fair, of which I am a part, has collected eight big boxes which contain, among other things, nearly 800 crossdressing fiction books which are intended for donation to this university. I have to note, Ms. Bob says there aren’t 800 books, but rather the same book written 800 times.

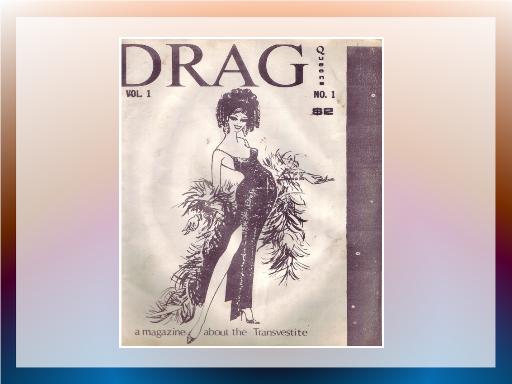

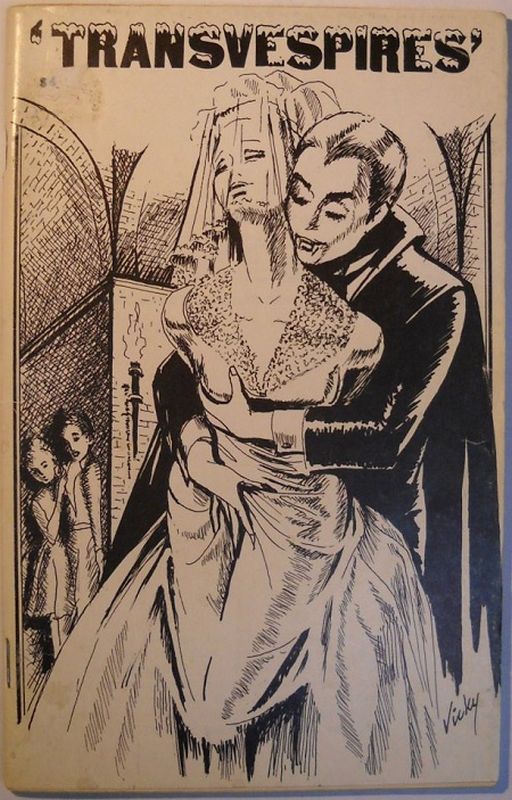

Maybe, though, there was only one Transvestpires. This cover, by the way, was illustrated by the Late Vicky West, who also did the covers for Lee Brewster’s Drag magazine..

I would guess that until now, at least, the Michigan collection has been the largest trans archive—but I never felt a need to say it. There’s no need to speculate on whose is biggest. What’s important is transgender materials are being preserved here in British Columbia, and in Michigan, and at many other places in North America and around the world.

That’s a bit of my history. I have been but one of many people striving to make sense of and preserve our culture and our history. Everyone in this room has been similarly engaged. I applaud you all for your hard work, for your passion, and for your love of our history.

Something remarkable happened over the past twenty or twenty-five years. We came to understand the importance of our history and we set to work rediscovering it. Due to the hard work of those in this room and many others, a significant portion of our history is now physically and intellectually safe and available for inspection. Transgender studies is now an academic discipline—that was an amazing announcement last night from Susan Stryker about the establishment of a Department of Transgender Studies at the University of Arizona— and many among our numbers are now teaching our history to young people in academic settings around the world. I feel privileged to have played a small role in helping this come to pass.

I promised to speculate a bit about the future. I’d like to end by sounding a cautionary note about a part of our history that is relatively new—or perhaps I should say about something with which I have recently become concerned.

I’m taking about our electronic lives, and especially about our engagement in social media. The internet has been huge in our community, and yet our electronic history is ephemeral. What happens to our Facebook posts or tweets when they scroll upwards and disappear from our screens? What happens when we forget our passwords or when a company holding our archives is purchased or goes out of business or when a company decides our files are inactive and purges them? Over lunch last fall, Hawk Stone told me went to retrieve some critical trans activist records stored online and found they had been erased. He’ll be talking about that right here in a few minutes, and I urge you to listen.

Who is archiving all those transition vlogs on YouTube? What happens when we are 20 years old and lose our unbacked-up cell phones with all our photos and messages or we lose our flash drive or our unbacked-up hard drive dies? What books and magazines and films were fifty years ago, social media is today. For many young trans people, their entire experience plays out in the cloud and in bits and bytes on their electronic devices. It would be a shame if this rich history were to disappear forever. I have been happy to learn this weekend that some of you are already on this.

Thank you.