Gender Reassignment Surgeries in the XXth Century (2015)

Source: Denny, Dallas. (2015, 25 April). Gender Reassignment Surgeries in the XXth Century. Workshop at 9th Transgender Lives: The Intersection of Health and Law Conference, Farmington, CT. Topmost photo by Karen Marie

Gender Reassignment Surgeries in the XXth Century

Workshop Presented by Dallas Denny

Transgender Lives Conference, Farmington, CT

25 April, 2015

I’ll start by saying this is not an exhaustive history or a comprehensive list of early surgeons. If you wish too add the name of a surgeon, please feel free to jump in.

Gender reassignment surgery has not been limited to modern times. The hijra on the Indian subcontinent have been performing castration and penile amputation on one another (and sometimes on unwilling recruits) from antiquity. Castration was widespread in Europe and Asia and was usually forced.

In the case of the hijra, surgeries are based on group identity. Reasons for castration in Western cultures ranged from rending males docile to making them incapable of fertilizing females (making them ideal guards of harems) to punishing those vanquished in battles. The castrated were often put to work in bureaucracy and palaces; many, in fact, were Black.

I should note ancient “castrations” often consisted of removal of all external male genitalia.

The Roman Catholic Church castrated boys in considerable numbers from the 1500s until 1903. I found one case of forced church castration as late as the 1950s in The Netherlands. The Church’s purpose was to remove testosterone so soprano voices of choirboys would not change with puberty. Voices of the castrati were considered sublime. In the 1950s cases the purported purpose was to prevent homosexuality, or, in at least once case, for reporting sexual abuse by a priest.

Castrations and especially penectomies performed before the development of antibiotics were life-threatening and often fatal. Castrations of unwilling subjects continues today, thankfully in reduced (although still considerable) numbers.

Trans people, of course, seek genital surgeries for self-expression—although I should note that in South Africa in the past and in Iran for the past twenty or so years, homosexual men have been encouraged to accept gender reassignment to avoid legal punishment (death, in the case of Iran).

Now to the point: surgeries in the XXth Century.

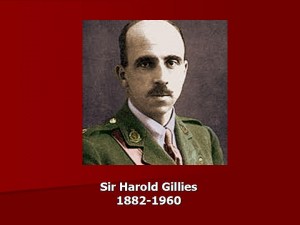

The techniques used in modern plastic surgery—including GRS—were developed almost exclusively by this man, who is considered the father of plastic surgery. His name was Harold Gillies. Born in New Zealand, Gillies became an otolaryngologist in London. In WWI he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. When he saw French surgeon Hippolite Morestin do a skin graft, Gillies established a facial injury award which was soon expanded into a hospital.

Gillies reconstructed the faces of hundreds of mutilated soldiers and in so doing invented techniques like the skin flap.

In preparing this workshop I found this quote about Gillies. I have known of his work for decades and it was interesting to get a glimpse of the complete man.

“A great golfer, professional- standard violinist, rowed in the boat race for Cambridge and won. In fact, he would walk around with an oar on his shoulder. And he had an alter ego — this is what interested me — called Dr Scroggy. He would disguise himself as a Scottish surgeon and would go into the ward at night, in his own hospital, where he had banned alcohol, and serve the men champagne and oysters. He encouraged theatricals, performances and skits, and there was a lot of cross-dressing. He was aware of the trauma he was dealing with. His solution was fun, which was remarkable really.”

— Curtis, 2014

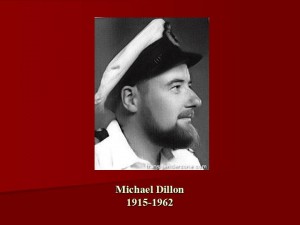

In addition to his facial work, Gillies reconstructed damaged genitals of soldiers and in some cases created new genitals. In the mid 1940s he was approached by transman and fellow physician Michael Dillon and as a consequence performed one of the first FTM genital surgeries.

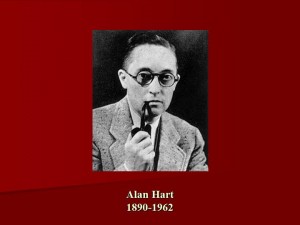

Dillon was preceded by three decades, however, by U.S. physician Alan Hart, who convinced Dr. Joshua Gilbert to do a hysterectomy so his menses would cease. Gilbert published the case report in Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease in 1920.

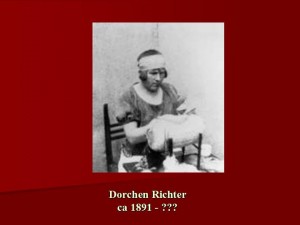

The first documented MTF surgeries seem to have occurred in the early 1930s, in the Berlin laboratories of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld. The first were Hirschfeld’s domestic employee Dorchen and Danish painter Lili Elbe.

Dorchen had been castrated at her request in 1922 and had genital surgery by Ludwig Lenz-Levy and Felix Abraham in 1931. So did Lili Elbe. Abraham published the case reports of Dorchen and Lili Elbe that same year.

Elbe’s story was hauntingly told in 1933 by a friend publishing under the pseudonym Niels Hoyer, retold in I think a beautiful way as fiction by David Ebershoff in 2000 in The Danish Girl, and is right now in post-production as a feature film.

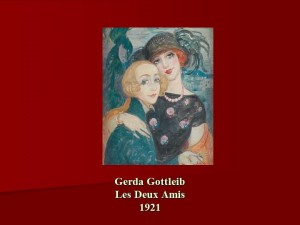

What to me is most striking about Elbe is her enduring and loving relationship with her wife, Gerta Gottleib. Gerta was also a painter and her favorite subject was Lili, who she often used as a model, as in this painting from 1921, ten years before Lili’s surgeries.

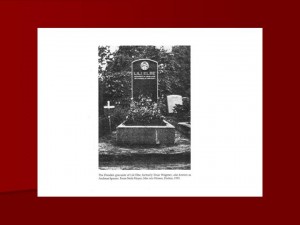

Lili Elbe underwent five surgeries, the last of which (transplantation of a uterus in the days before tissue rejection was recognized), proved fatal. This image of her grave in Dresden is the frontispiece for my 1994 book Gender Dysphoria: A Guide to Research.

In the mid-1950s there was a go-to place for MTF surgeries: Casablanca. There, Georges Burou operated on people whose names might be familiar: Amanda Lear, Bambi, Coccinelle, April Ashley, Jan Morris, and many others whose names you might not know, from all over the world. By 1974 he had performed nearly one thousand vaginoplasties, mostly on trans women, and in his career he is said to have done more than three thousand. In the mid 1970s his fee was five thousand dollars, which included the costs for a two-week stay at his Clinique du Parc.

Burou innovated many of the techniques used today in inversion GRS—and in particular the anteriorly pedicled penile skin flap and a number of later surgeons, including Stanley Biber, credited him for their own techniques.

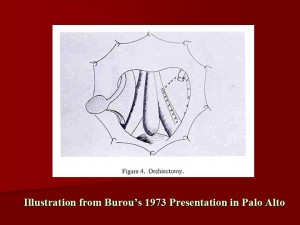

Burou’s only presentation to his peers, at least to my knowledge, was in 1973, when he presented at Stanford University at the Second Interdisciplinary Gender Dysphoria Association Symposium. His talk is included in the book that resulted from the meeting.

The first American GRS surgeon was, it is believed, Elmer Belt, who was based primarily at UCLA. His practice started even earlier than Burou’s, in the late 1940s or very early 1950s, as he was doing surgesries before 1952. He stopped performing operations at UCLA in 1954 because of objections from his peers and in 1962 because of objections from his family and complaints about his bedside manner.

Unlike Burou, Belt did FTM surgeries as well as MTF surgeries, including that of Mario Martino.

For a fascinating early history of primarily west-coast based transsexualism, I recommend JoAnne Meyerowitz′ excellent How Sex Changed.

The mid-1960s saw the formation of gender identity clinics at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Minnesota; soon there were more than forty university-affiliated clinics scattered throughout the U.S. They operated until 1979, then abruptly closed as the result of a scheme developed by psychiatrists Paul McHugh and Jon Meyer of Hopkins.

Surgeons at these clinics included Claude Migeon, Howard Jones, Howard W. Jones, and Milton Edgerton at Hopkins, Stanley Laub at Stanford, David Foerster in Oklahoma, Donald Hastings, J.W. McRoberts, and dozens of others just here in the U.S. There were surgeons in Great Britain and assorted other European and Asian countries, Australia, and other places.

This group of surgeons created many improvements big and small for vaginoplasty techniques and published widely. When the clinics closed some of these surgeons turned to other patient populations; others—Donald Laub is one instance— went into private practice.

I don’t plan to get into a discussion of variations on procedure, but I should say that while most vaginoplasties continued to use skin inversion techniques pioneered by Gillies, Burou, and Belt, Laub and others championed use of a section of large intestine to line the neovagina.

The surgeons at the clinics pioneered FTM top and bottom surgeries. Early chest reconstructions were not aesthetically pleasing, and phalloplasty required a number of expensive surgeries and yielded nonfunctional and mostly non-aesthetic male parts, but progress was made when skin from the forearms began to be used. It wasn’t until late in the century, however, that the clitoral surgery metoidioplasty came into more than occasional use.

Improvements in technique were mirrored by improvement of results. Surgeons learned what could be done with skin flaps, and, by pushing the limits, when blood supply became reduced enough to lead to necrosis and rejection. To this end, most surgeons did not finish modeling the labia on the first surgery, but brought their patents back for a second, optional surgery. They learned how to reduce strictures of the urethral meatus, how to dissect the vaginal cavity without creating a fistula between the neovagina and the rectum, and how to maintain nerve sensitivity so patients would be orgasmic. They shared their knowledge in the pages of journals like Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and at meetings of the newly-formed Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association.

In the days of the gender clinics, access to hormones and surgery was strictly regulated and difficult to obtain—and most applicants to the clinics were refused treatment. After their abrupt closure surgery was hard to get for a time, but eventually a free-market system arose that made GRS obtainable for just about anyone who could pay the fees. They didn’t have to advertise; transsexuals found them by word of mouth.

Notable among this group of surgeons was Stanley Biber. Biber was a Colorado county doctor who, after studying diagrams from Georges Burou and Johns Hopkins, did his first MTF GRS in 1969. By the 1980s he was doing many surgeries and by the 1990s Trinidad, Colorado became informally known as “the sex change capitol of the world.” Biber performed phalloplasties as well as vaginoplasties and did thousands of surgeries before his death in 2006.

Other surgeons of the 1980s and 1990s—there were many— included K.V. Ratnam in Signapore, Yvon Menard in Montreal, Neal Wilson in Detroit, Michel Seghers in Brussels, Eugene Schrang in Wisconsin, and David Gilbert in Norfolk, Virginia. My surgery was done by Michel Seghers in 1991 at a cost of just $4000.

Most of these surgeons followed the guidelines of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, requiring letters from mental health professionals documenting the real life experience, but there were abuses and abusers. Some surgeons, for instance, David Gilbert, adhered to the medical model, requiring applicants to pass arbitrary criteria in order to qualify for surgery. Neal Wilson enthusiastically performed expensive bowel resection vaginoplasties under insurance until Blue Cross/Blue Shield shut him down.

By far the worst surgeon ever to have practiced GRS was John Ronald Brown. In the 1960s Brown was identified by Viva magazine as the worst plastic surgeon in the U.S. His demeanor and behavior was beyond strange. In 1977 Brown repeatedly lost his license to practice medicine in California and other places; he continued to do GRS and repeatedly went to jail for it. By the early 1990s he was practicing in Tijuana under a pseudonym. An army of transsexual former patients solicited new business, claiming “John Brown makes the most beautiful pussies.”

Brown was a horrible technical surgeon who “didn’t know how to make a straight incision.” He operated on anyone who had the money. His would operate in motel rooms and on tabletops, and was known to leave patients in their cars immediately after surgery. His patients often smelled like they were dead because of necrotic tissue, and were often in horrible pain.

From 1990 onward I issued periodic advisories warning about Brown, but transsexuals continued to seek him out. He might still be practicing had the body of 79-year-old Philip Bondy not been found in a hotel room in San Diego County. Brown, it transpired, had removed Bondy’s healthy leg— at his request.

When newspaper articles reported San Diego District Attorney couldn’t figure out why Brown had done the operation, I phoned and spoke to her assistant, telling him about opotemnophilia, a body dysmorphic disorder in which individuals fetishize the removal of their healthy limbs. With motive established, Brown went to trial and was sentenced to 15 years to live in prison.

It didn’t occur in the Twentieth Century, but it did early in the Twenty-First, in 2003. Ob/Gyn specialist Marci Bowers became the first transperson—and the first woman— to perform GRS. She took over the practice of Stanley Biber, who was retiring. After some years in Trinidad, she moved her office to San Mateo, California, where she continues her work. A second transwoman, Christine McGinn, now does GRS as well.

The Twentieth Century saw the development of techniques which made plastic surgery possible, the use of those techniques in gender reassignment surgery, and a steady and ongoing refinement of procedures. Along the way what was experimental became accepted clinical practice for the treatment of transsexual people.

Works Cited

Abraham, F. (1931). Genitalumwandlung an zwei maennlichen transvestiten (Genital alteration in two male transvestites). Zeitschrift Sexualwissenschaft, 18, 223-226.

Burou, G. (1973). Male-to-female transformation. In D. Laub & P. Gandy (Eds.), Proceedings of the Second Interdisciplinary Symposium on Gender Dysphoria Syndrome, pp. 188-194. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Medical Center.

Curtis, Nick. (2014, 26 August). Harold Gillies, the man who mended broken soldiers. The Evening Standard.

Gilbert, Joshua A. (1920, October). Homo-sexuality and its treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 52(4), 302-321.

Hibbard, Laura. (2012, 19 March). Dutch Roman Catholic church castrated boys as “treatment” for homosexuality. Huffington Post.

Hoyer, N. (1933). Man into woman: An authentic record of a change of sex. The true story of the miraculous transformation of the Danish painter, Einar Wegener (Andreas Sparrer). New York: E.P. Dutton & Co.

Meyer, J.K., & Reter, D. (1979). Sex reassignment: Follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 36(9), 1010-1015.

Meyerowitz, J. (2002). How sex changed: A history of transsexuality in the United States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Moore, Michelle. (2002). TG in history: Butcher John Ronald Brown. TG Community News, 19-24. Michelle’s article is reproduced on my website here.

Segal, Ronald. (2001). Islam’s black slaves: The other black diaspora. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.